Exploring the Work of Women Directors in Hollywood

As part of Tyler Davis’ directed study, she and Natalie McKnight (left), dean of CGS, met weekly via Zoom to discuss and analyze female-directed films. Photo courtesy of Tyler Davis

Exploring the Work of Women Directors in Hollywood

COM student spent her summer partnering with CGS dean in directed study project

As a young filmmaker, Tyler Davis was looking forward eagerly to scouring the list of nominees for best director when the 2020 Academy Award and Golden Globe Award nominations were announced. When Davis (CGS’20, COM’22) saw the finalists in the directing category, her excitement gave way to disappointment.

The roster for both lists included Martin Scorsese, Todd Phillips, Sam Mendes, Bong-Joon Ho, and Quentin Tarantino. All men. This despite the fact that a number of women had helmed critically praised films last year, among them Greta Gerwig (Little Women), Lulu Wang (The Farewell), and Marielle Heller (A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood). In fact, only five women in the Academy’s 92-year history have been nominated for best director, and only one—Kathryn Bigelow—has taken home the top prize, for 2009’s The Hurt Locker.

“No one can name a female director, but plenty of people can at least name Steven Spielberg (Hon.’09),” says Davis. “It felt like I was missing out on a whole world of filmmaking that I definitely hadn’t learned much about.”

Determined to change that, she embarked on a directed study this summer, focused on female directors and the obstacles they face in the industry, working with Natalie McKnight, dean of the College of General Studies. Davis was specifically interested in analyzing female-directed films to discover whether a distinct female voice exists.

While McKnight’s expertise is literature—she’s a renowned Charles Dickens scholar—she has taught film at CGS, and was quickly drawn to Davis’ proposal. “She’s just a very intelligent, creative, passionate person,” McKnight says.

The two worked together to craft an official proposal and syllabus for the directed study, and they’ve been meeting weekly via Zoom since mid-May.

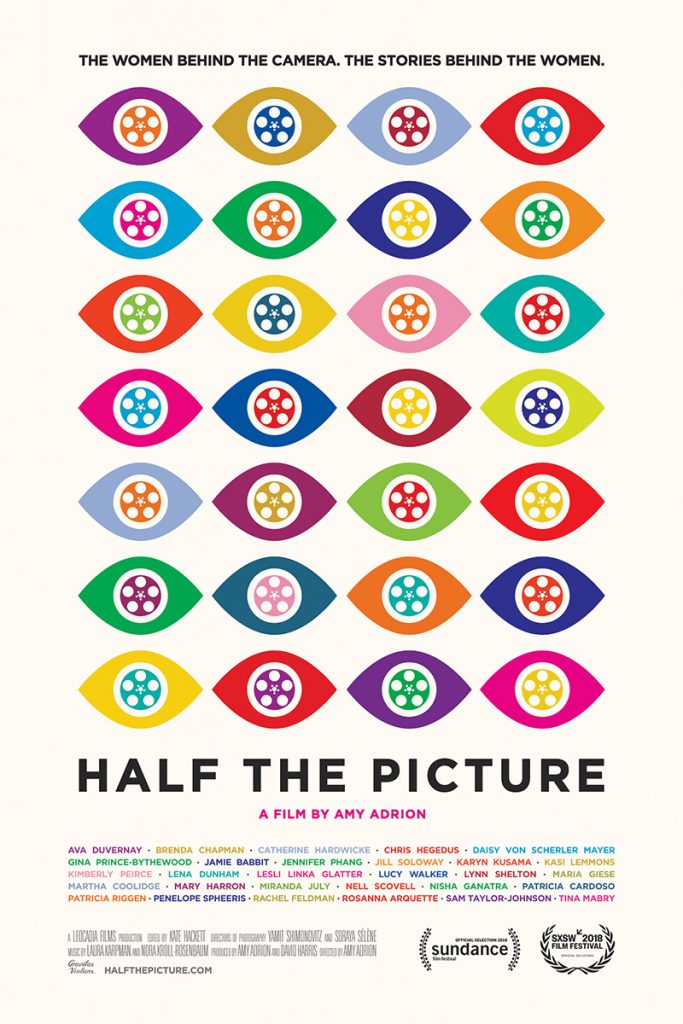

They began their research with Half the Picture, a 2018 documentary about the gender gap that exists among the ranks of Hollywood directors. According to the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film, of the 1,300 top-grossing films from 2007 to 2019, fewer than 5 percent were directed by women.

To McKnight, the documentary served as an important framing for Davis’ directed study. “We’re getting less than half the picture on the female perspective on everything—on women themselves, on their relationships, on men,” she says.

From there, the two watched Gerwig’s Lady Bird (2017), which garnered a best-director Oscar nomination for her, Karyn Kusama’s Girlfight (2000), Jane Campion’s The Piano (1993), Mira Nair’s Monsoon Wedding (2001), and Dee Rees’ Mudbound (2017).

“I tried my best to get a diverse group of female directors, because minority women definitely experience the most difficulty in the film industry,” Davis says.

As part of the project, she wrote a response paper for each film, pinpointing important motifs and placing them in the broader context of the study. While the papers satisfied the syllabus requirements, it was the weekly one-on-ones that proved most fruitful for both Davis and McKnight. “We had a lot of amazing conversations, and we discussed our own experiences,” Davis says. We shared our own film interests. I feel like I really connected with her.”

The two focused on recurring themes that were present in each movie. After watching all five films, they had similar takeaways. For Davis, one critical through line was that each film passed what’s known as the Bechdel test, a measure of female representation in works of fiction. There are three criteria: first, the film must have at least two named women, second, the two women must talk to each other, and third, they must talk about something other than a man.

While the Bechdel test can be a useful framework for analyzing female representation, the similarities Davis noticed in the films ran deeper than a mere checklist—they represented the distinct female voice she was after.

“They all had female leads who were the drivers of their own story, rebelling against some sort of status quo,” Davis explains. “And it was definitely rooted in patriarchal challenges and struggles that these women face. A lot of the female characters were stubborn in their beliefs and loyal to their well-being.”

She notes that none of the films she studied perpetuate rape culture, but rather, portray consensual sex, often with the women as the pursuers of love.

While both Davis and McKnight expected to see interesting and nuanced female characters, they did not anticipate the same for male characters. They were pleasantly surprised. McKnight says she observed emotional and physical vulnerability from male characters. “You don’t usually see that in male directors,” she says. “And I wasn’t going looking for that. I was really honing in on the female characters.”

One of the clearest examples of this dichotomy could be observed in Girlfight, a sports drama about a troubled teenage girl who takes up boxing. Davis contrasted it with the classic boxing film Rocky, focusing specifically on the difference between the love interests in the films, both (perhaps not coincidentally) named Adrian.

“The male hero, he always gets the girl, and the girl is always a side part of his character,” she says. “But in Girlfight, it was different. The main character’s love interest was a big part of the story, and his character also had a lot of depth.”

If what you perceive as a good whatever—CEO, CFO, director—is framed in that kind of metaphor that is heavily masculine, then who’s going to be the right fit for that? Well, of course it’s going to be some guy.

Going into the directed study, both Davis and McKnight had already seen Lady Bird, but rewatching it in the context of their research, each was struck by the mother-daughter dynamic. “That movie, when I watched it the first time, had already really impacted me,” Davis says. The second time, “I focused a lot on the relationship the girl has with her mother. That relationship is incredible.”

For McKnight, the mother-daughter dynamic in the film felt especially real. “I think Tyler really relates to the daughter, and I really relate to the mother,” she says. “So it was just very interesting to have that conversation with her.”

Their final takeaway was a bit more encompassing. Drawing from the documentary Half the Picture, the role of director “inherently has a masculine connotation to it,” says Davis. Both she and McKnight compared the role of a director to that of a military leader.

“We see this in a lot of industries,” McKnight says. “If what you perceive as a good whatever—CEO, CFO, director—is framed in that kind of metaphor that is heavily masculine, then who’s going to be the right fit for that? Well, of course it’s going to be some guy.”

But if instead you think about a director more as a nurturing presence than as general leading troops into battle, McKnight says, it offers a more inclusive interpretation of the role. “Mothers create life, mothers nurture, mothers evolve children into adulthood in the same way you would evolve a film project,” she says. “If we thought of the work in terms that are at least more open to a female-inflected leadership role, then maybe we would back women more in these kinds of positions.”

While the directed study closely followed the syllabus Davis and McKnight had created, the protests over racial injustice that swept the country this summer influenced their conversations and research. They decided to add Ava DuVernay’s documentary 13th (2016) to their list as well.

“Those conversations about this particular moment, specifically in relation to the protests going on and the outrage and sorrow [over] these acts of police brutality, that is—in my mind looking back over the last couple of months talking with her—deeply woven in there, into the fabric of this directed study,” McKnight says.

This summer was also challenging, of course, because of the coronavirus pandemic and its myriad impacts on everyday life. Davis says spending so much time at home on her computer has “frustrated my creativity,” but her experience with McKnight has reignited her passion for film. She plans to produce a short film this semester on the topic of female directors to conclude the study.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.