Katherine Kennedy’s Journey from Childhood Sadness to Howard Thurman Center Director

“My 32,000 Children.” Katherine Kennedy’s Journey from Childhood Sadness to Howard Thurman Center Director

Longtime center leader reflects on her remarkable path through journalism, politics, sports, and education

From her office in the Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground’s new home at 808 Commonwealth Avenue, Katherine Kennedy can look out onto campus and see what she calls her “32,000 children.” Photo by Jackie Ricciardi

She was the only Black girl in her homeroom, surrounded by a sea of white Jewish students. In fourth grade, she was hospitalized with tuberculosis, visited only by her parents for three solid years, traumatized by nurses who cut off her hair. College began with a scholarship during a period when schools were integrating—but it ended with a transfer, a degree, and no clear direction. And in matters of the heart, she found love, and lost love, before realizing that the most important person to love is yourself.

Katherine Kennedy, in the sunset of a remarkable 50-year career working in journalism, politics, the NFL, and higher education, is helping the next generation of ambitious young minds to look past skin color and cultural differences, find common bonds, see the good in people, stand up and be heard, and refuse to settle for mediocrity when there is so much work to be done.

The director of Boston University’s Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground for 20 years, Kennedy, now 75, led its move early this year from the George Sherman Union basement to a bright and airy building at the busiest corner on BU’s campus, directly across from the BU Bridge. Much has changed since that move. With the coronavirus pandemic upending BU life, Thurman Center spaces are being adapted into classrooms, its events pivoted from in-person to virtual Zoom gatherings, and the center’s hours extended to 9:30 pm. But Kennedy is still visible in her second-floor office, where she can see into the new center’s hallways and classrooms, or out onto the bustling street below. Wherever she looks, she sees family.

“When I became director of the Thurman Center, I remember thinking, OK, God, I got this. You have given me 32,000 children,” she says. “They keep me young. They keep me vibrant. They keep me learning, in many ways. So working on a college campus, I really feel fulfilled.”

And now, in this COVID-19 world, Kennedy must help the Thurman Center carve out its new identity.

“We are sensitive to students who don’t want to be stuck in their room, but we also don’t want to turn the Thurman Center into a studying space,” she says. “But we know students want a different kind of environment. How do we help them feel at home, when we can’t use our home the way it was intended?”

A childhood of challenges

We’re sitting in her office at 808 Commonwealth Ave. Glass walls surround us. And so do some mesmerizing pictures and magazine covers. There’s Barack Obama, Michelle Obama, Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59), US Senator Edward Brooke (LAW’48,’50, Hon.’68) (R-Mass.), and former longtime Boston Globe editor Thomas Winship. All of them, either directly, or through their mere existence, had an impact somewhere along the way on her journey.

About that journey…

Imagine starting every day at school and looking around and feeling like you are different from all the other children. There were a few other Black girls at Kennedy’s Dorchester school, but not many, and none in her homeroom. They were mostly Jewish. She went to a Congregational church. “It was probably the very first time that I was exposed to other folks’ ethnic and cultural lives,” she says. “So, I had Jewish girlfriends who invited me home for seders. Or I went to bat mitzvahs. So, even though there was segregation, you were exposed to other cultures.”

Photo by Jackie Ricciardi

Photo by Jackie Ricciardi

Kennedy’s office walls showcase a Who’s Who of politics, sports, and culture. Photos by Jackie Ricciardi

And then, in a blink, she was alone. Struggling with her breathing, she was diagnosed with tuberculosis at age nine and quarantined in a children’s sanatorium in Boston—for three years. From fourth grade to seventh grade, she was tutored at her bed, visited only by her divorced parents once a week. “It obviously had a deep impact on me,” she says. Her parents always brought her games and toys and cookies and candy, but being isolated as a child, especially a Black child, was painful—and at the same time, valuable. “I was always open to being a part of other people’s life experiences,” she says, “and then inviting them into mine, as well.”

But when nurses washed her hair and it frizzed up, they didn’t know what to do with it. So they cut it off. “That was pretty traumatic, and when my mother came to see me, she was horrified,” Kennedy recalls.

She made it through high school and was offered an opportunity to attend Mount Holyoke College in 1963. But it wasn’t a positive experience. Suffering from severe asthma, she was encouraged by doctors to move to a drier climate out West. She landed in downtown Los Angeles, living at home with her father while studying liberal arts at Pepperdine University.

After graduating, she came back to Boston, expecting to either be a teacher or a nurse. Then, through her church, she had a conversation that would change her life.

Covering history

Kennedy worked briefly for a Boston bank, but was bored stiff. Making phone calls for her church one day, she reached a gentleman she knew from church. When he realized who she was, he asked to meet with her.

“I went and had dinner with him, and I trusted him because he went to my church,” Kennedy says. “He said he worked at the Boston Globe, where he headed the community affairs department, and offered me a job.”

Boston in the late 1960s was literally a city of Blacks over here, whites over there, and things were building toward an ugly confrontation. Kennedy wrote articles about social service agencies for the paper and helped the Globe build relationships in the community. Thomas Winship asked her how she was doing and said he had a new job for her—working for him. And there was more.

He saw promise in Kennedy, and he tossed a bunch of college catalogs on her desk and told her to look them over. They were great schools. She could not afford any of them.

“I said, ‘What is this for?’” she says. “He said, ‘This is for you. You’re really a good writer, and you should consider going to grad school.’”

When I became director of the Thurman Center, I remember thinking, OK, God, I got this. You have given me 32,000 children. They keep me young. They keep me vibrant. They keep me learning.

When she explained that she hadn’t been saving for graduate school, he told her the Globe would pay for it. “It was an amazing gift,” she says, “because I didn’t have to sign any documents saying come right back. I didn’t have to make any promises.”

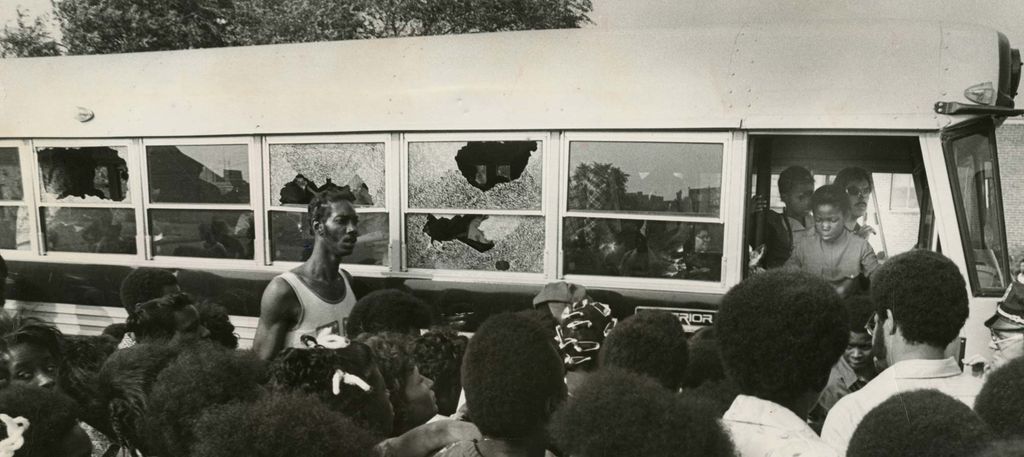

She took a class to learn to type faster, and a speed writing class to take notes quicker. And then, on the Globe’s dime, she completed a fellowship program at Columbia University and returned to the paper in the early 1970s, a historic time in Boston. The fight over desegregating Boston Public Schools was raging. There were schools in Roxbury that were 90 percent Black and schools in South Boston that were almost 100 percent white, and eventually Black parents began pulling their children out and boycotting Boston schools. Kennedy was the only Black reporter from Boston who had attended Boston Public Schools and still lived in the community and knew all the players. She covered weeks and months of meetings and arguments, and then it got worse. A school bus carrying about 50 teenagers, who were mostly Black and Puerto Rican, was stoned on its way to school and had to turn around, and parents were demanding to meet with the mayor. Kennedy covered it all.

“I go to a pay phone and call the city desk and tell them the bus is getting stoned, there were 300 angry parents here saying they won’t put their children on buses tomorrow, and I told him to send reporters,” she says. “And the city editor, I’ll never forget, said to me, ‘Kennedy, you are the reporter.’”

Her first major story as a rookie reporter ended up on the front page of the Globe. And her coverage continued. She rode on one bus with students that was also stoned, ducking beneath glass and rocks, listening to adults screaming, “Niggas go home.” Ultimately, her stories became part of the work that won the Globe the 1975 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service.

Healing the NFL

Her journalism work fueled Kennedy’s drive to do more good, to help more people, to have another, what she calls, “life-changing experience.” In fact, the rest of her career would be filled with those.

But, along the way, she would also experience heartbreak.

“Never married. No children. I was a runaway bride,” she says nonchalantly, before launching into a story about falling in love with a man who lived in Philadelphia. They were three days from marrying when he sprung some surprises on her—a new house in the suburbs, an expectation that she would be home waiting for him at the end of the day.

“Women then [mid-1970s] didn’t really have careers,” she says. “But I don’t have any children, and I’m not looking to get pregnant right away.” She knew the relationship could never work when he refused to attend The Nutcracker with her. “I didn’t cry. I didn’t get hysterical. I remember going into the kitchen, my mother and grandmother were sitting at the kitchen table, and I said, ‘How do I cancel this wedding?’”

She called her father to tell him not to come from California, and that was that. “My jobs were important to me,” she says. “They weren’t just jobs. And I wasn’t willing to just give them up.”

Yes, she says, there is occasional loneliness. But she has filled her life with friends, hobbies, and passions, from volunteering to travel to her tight bond with the women of a wine appreciation club, called Divas Uncorked.

A photo of Katherine Kennedy working with former Boston Globe editor Thomas Winship hangs on the wall in Kennedy’s office. Photo by Jackie Ricciardi

A crowd watches as a bus carrying students returns to Columbia Point with broken windows on Sept. 12, 1974, the first day of school under the new busing system put in place to desegregate Boston Public Schools. The system was met with strong resistance from many residents of Boston s neighborhoods. (Photo by Donald Preston/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

Kennedy’s journalism career launched with the help of the famous Boston Globe editor Thomas Winship and included her coverage of the 1970s-era busing crisis. Photos by Jackie Ricciardi and Donald Preston/Boston Globe via Getty Images

She got a call from the University of California, Berkeley, asking her to help launch a minority journalism program, and the lure of returning to the West Coast was strong. “I reluctantly accepted the position,” she says, “not because I was anxious to go to California or leave my writing career, but it was an opportunity to get more people into the business by setting up this fellowship that trained minority news reporters.”

After living on the East Coast in a largely segregated society, Kennedy was surrounded by a more diverse population in California, especially of Asians and Hispanics, and even Native Americans. She didn’t realize it at the time, but the experience prepared her for the next chapter. “Being forced to live, learn, and socialize with people from all different ethnic and cultural backgrounds in California, I believe truly prepared me to be totally open to never living in a segregated society,” she says.

A few years later, she was headed back East. After the National Football League players went on strike for 57 days in 1982 to demand a greater share of league revenue, the NFL needed some crisis public relations work to repair the fractured relationship with the players’ union. The NFL asked Kennedy to start a program that helped players forge careers off the field. But when some teams hesitated, especially at the idea of a Black woman in charge, the New England Patriots stepped forward. They would hire Kennedy to do the work and have their program serve as a pilot for the league.

She worked at the old Sullivan Stadium in Foxborough and helped some of the biggest names in Patriots’ history, from John Hannah to Stanley Morgan to Andre Tippett. “The thing that I’m most proud of is that we worked to develop the degree completion program for athletes,” she says. “That became the national norm that the NFL and all the other professional sports endorsed.”

Building bridges at BU

When John Silber (Hon.’95) took time off as BU president to run for governor in the late 1980s, he hired Kennedy to help with his fundraising. And when he came back to BU, a position was waiting for Kennedy as well, in the Office of Development & Alumni Relations. Her two biggest projects became the creation of the building that now houses the Questrom School of Business and the restoration of Marsh Plaza.

But if there was ever a job that seems as if it were custom-built for Kennedy, after a career in journalism, politics, business, and higher education, and a lifetime surrounded by people from all cultures and backgrounds, it was the role that she took on in 2000, and still holds today: director of the Thurman Center, a place for students to listen, learn, and bond over their likes and dislikes, as well as meditate, study, or do whatever else it is that college students today do.

But it is not, Kennedy says firmly, a Black student center.

“Many of my colleagues would always send issues around Black students to me or to the Thurman Center,” she says. “And I would have to let them know that, yes, I can deal with that. But don’t view us as the Black center. That’s not who we are. That’s not what we’ve ever been.”

She says Black students will occasionally come to BU expecting there to be a center for them, especially in recent years as the population of Black students has risen. “They would be upset that it wasn’t the Black center,” she says. “Some of them sort of hoped that this was exclusively for them. And then when they were told it was not, they were disappointed.”

Her challenge, she says, has been to show all BU students—her “32,000 children”—that it’s a place for them to feel supported. And if they want to claim a small piece of turf for their group, then claim it, just like anybody else.

“And make yourself at home in the center,” she says. “But I would also make sure that they understood that there are times when people want to be with their own [crowd], whatever that is. But let us not forget that part of why you’re here getting an education is to prepare you to go out into the real world. And many of the jobs and circumstances that you will encounter will not be of just one ethnicity, one culture.”

It’s a lesson Kennedy has learned over and over—and that she wants to leave with others, especially as the new Thurman Center sits literally on a bridge, and in Boston, a city with a history of racial tension. It’s a giant metaphor not lost on Kennedy.

“We work to bridge relationships with people,” she says, “and so being on the bridge helps remind me and others that that’s part of our purpose.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.