POV: Trump’s Call for a National Garden of American Heroes Misses the Point

Photo by Alex Brandon/AP

POV: Trump’s Call for a National Garden of American Heroes Misses the Point

Rather than new statues, we need to ask questions that lead us to a collective understanding of our history

Is memory the same as history?

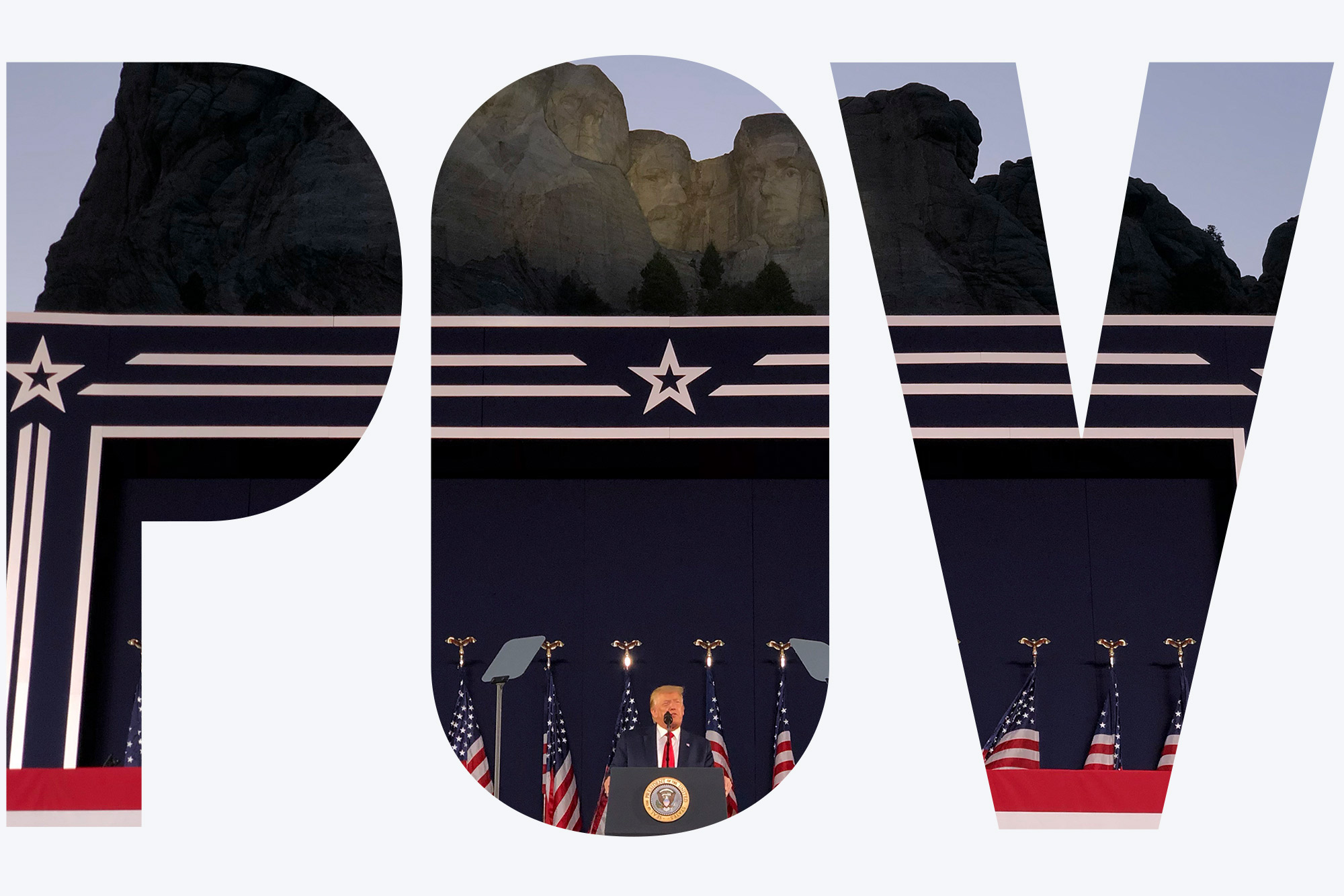

On July 3, 2020, President Donald Trump announced an executive order to build “a vast outdoor park” with monuments to “the greatest Americans to ever live.” At a rally at Mount Rushmore, the president responded to what he called attacks on “our collective national memory.” Reaction was swift, both from proponents who appreciated his choices and from those who lamented that none of the 30 proposed honorees were Latinx or indigenous. Part of the trouble with the president’s proposal, though, is that it assumes not only a depoliticized production of “collective national memory,” but also a stable and static “memory” that is sacrosanct for all time. Rather, collective national memory is a construction and the making of it exposes relationships of power. Inasmuch as it is collective and then popularized, the process often leaves out vast segments of the nation’s population.

In the last few months, activists, scholars, local officials, and national museums have debated statues and flags honoring Confederates, monuments to slaveholding, or imperial statesmen, and replicas of purported discoverers like Christopher Columbus. Here in Boston, the Boston Art Commission voted to remove the Emancipation Group sculpture on display in Back Bay. The statue is a copy of artist Thomas Ball’s Washington, D.C., memorial that depicts a paternal Abraham Lincoln standing over a kneeling formerly enslaved man. On BU’s campus, President Brown tasked a committee with exploring the appropriateness of our mascot’s nomenclature, named at least partly as a reference to the Rhett Butler character in the Lost Cause 1930s film Gone with the Wind. While some of these icons have long been the center of local movements to remove, contextualize, or historicize them in some way, the recent energy has come as a result of the uprisings in response to the Memorial Day Minneapolis police murder of George Floyd, a Black man. The horrific video of Floyd’s murder, coupled with the killings of Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery and the experiences of Black folks trying to birdwatch, drive, or even just hand out extra donuts in Newburyport, Mass., for example, has reprised a reckoning on racism and for racial justice, bringing back (for some) the debate on the importance of cultural iconography.

Ignoring for a moment the irony of President Trump’s reference to collective national memory at an event on sacred and stolen Lakota land, the Six Grandfathers Mountain in Black Hills, South Dakota, we could pause to reflect on what collective national memory is and its relationship to monument building. Most of the commemorative statues to the Confederacy that have been coming down since the 2017 events in Charlottesville, Va., come out of a century-long process of Civil War memory-making. These artifacts, and not just the ones in bronze and stone, but also the names of military bases and schools from elementary to colleges across the country, visual representations in film and product advertisements, and state departments of education curricula were created in a fraught period of national and legal racial segregation, state-sanctioned racial violence and lynchings, and a resistance and liberation movement against Jim Crow.

Yale historian David Blight, who gave the Howard Zinn Memorial Lecture last year at BU, writes about this in his book Race and Reunion. By the time President Woodrow Wilson made his national speech meant to reconcile the country at the 50th anniversary of Gettysburg in 1913, Black Americans had already spent decades experiencing violent voter suppression. Wilson’s speech, to an audience of former Confederate and (only white) Union veterans, intentionally focused on their sacrifices, even while Black soldiers, both those who had given their lives in the war and those still alive (and fighting for pensions), were absent. Wilson encouraged those in attendance, and ultimately the nation at large, to reflect on white manhood and heroism, not the causes of the war, “its genesis,” he said, “nor its significance.” Individual states and the federal government had invested nearly $2 million in the multiday “Peace Jubilee” at Gettysburg. Films like D. W. Griffith’s Birth of A Nation (which Wilson screened at the White House upon its release) and Gone with the Wind soon followed, as did a segregated military in World War I, continued Black voter disenfranchisement, racial science and eugenics, and anti-Black violence in Tulsa, Okla., and elsewhere. Over the next 50 years, we would see public and privately funded monument building to the Confederacy, coupled with an erasure of the causes of secession and the war.

So, statues like that of Stonewall Jackson, Theodore Roosevelt (at both the Smithsonian Museum and the Natural History Museum in New York), and the “Father of Gynecology” J. Marion Sims’ statue in New York’s Central Park, and others that are being critiqued and removed, either by municipalities or by members of local communities, came into their public existence through a very deliberate memorialization effort at a particular historical time with its own political realities and national needs. The Lincoln Memorial, its reflecting pool, and much of what we have come to know as the National Mall in Washington, D.C., were part of this Jim Crow reimaging effort. An intentional city beautification project designed by a Congressional committee, the D.C. Board of Trade, and private architects, it and the Jefferson Memorial were meant to make DC “an open-air cathedral to American Patriotism.” Over the course of two decades after World War I, both sites opened with unveiling ceremonies to segregated audiences in the racially segregated US capital.

Memorialization of historical events and individuals, whether in popular culture, school curricula, or in traversed spaces, shapes a public archive for as long as these artifacts remain. These representations emerge from and mobilize false genealogies of the past in service of the present, telling us who and what is valuable. Collective national memory is neither organic nor objective, and more often than not it reflects a selective historical narrative, while also obfuscating the power to craft that narrative. We are in the midst of a full-throated call to review flawed national memories, not only about the Confederacy, but about the institution of slavery and about Native American genocidal policies and practices. Rather than new statues, we need to ask different questions, ones that lead us to what Frederick Douglass called “a usable past,” a collective understanding of our history that foregrounds reparative justice and gives us tools in our work to more equitably restructure society.

Paula Austin is a College of Arts & Sciences assistant professor of history and of African American studies; she can be reached at pcaustin@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.