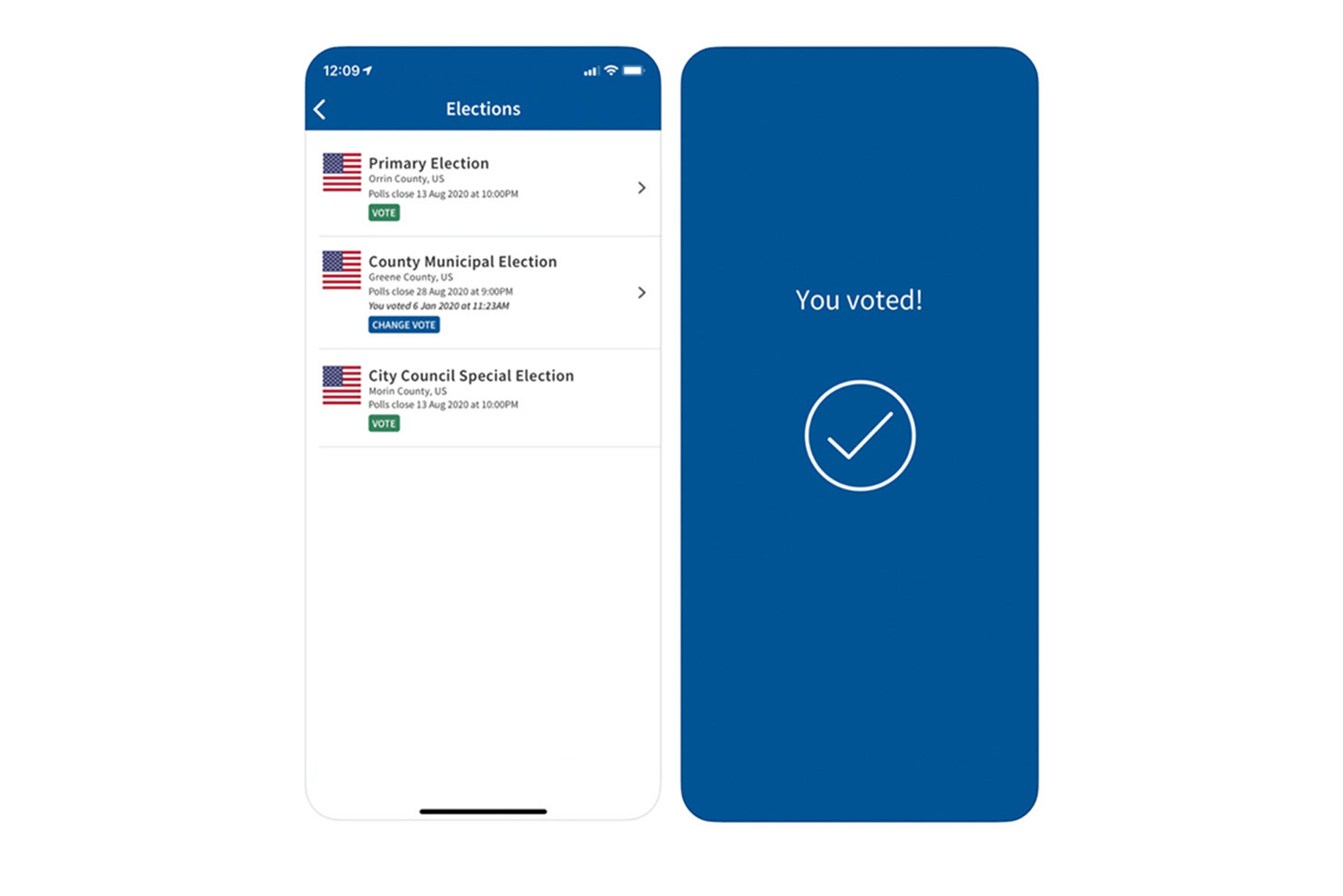

The BU/MIT Technology Law Clinic at the School of Law helped reveal critical security flaws in a smartphone app that would let voters cast their ballot from anywhere.

MIT researchers say they found critical flaws in the voting app created by Boston start-up Voatz, and the BU/MIT Technology Law Clinic at the School of Law helped reveal them to officials.

Vote on Your Phone? BU School of Law Clinic Helps Expose Security Flaws in Voter App

MIT students, working with clinic, bring election app research to Homeland Security

The BU/MIT Technology Law Clinic at the School of Law has helped reveal critical security flaws in a smartphone app that would let voters cast their ballot from their kitchen, their car, or from anywhere in the world.

Over the last three months, a trio of MIT researchers found flaws in the app created by Boston start-up Voatz, flaws that hackers could exploit to interfere with votes and voter privacy. Their paper outlining the issues is now available for download.

The Technology Law Clinic assisted the MIT researchers—Michael A. Specter, James Koppel, and Daniel J. Weitzner—in disclosing their findings to Homeland Security officials. Homeland’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) shared their findings with Voatz and officials in several states who were using the app in pilot programs on Android phones.

The researchers’ discoveries, first reported by the New York Times Thursday, were disputed by Voatz, which said it found “fundamental flaws with their method of analysis, their untested claims, and their bad faith recommendations.” At least one Voatz client—a county in Washington state—has pulled out of the trials, according to the Times. Other clients vow to continue.

There is no sign anyone has tried to hack the Voatz app, which has been used by hundreds of voters in the pilot programs. But after a different flawed app all but derailed last week’s Iowa Democratic caucuses, election security, and the technology involved, is receiving heightened scrutiny.

Thanks to an attorney-client relationship with the LAW Technology Law Clinic, the researchers remained anonymous until this week. The clinic, comprising two lawyers and more than a dozen students, provides pro bono legal advice to undergrad and grad students from BU and MIT who encounter legal issues around security, intellectual property, and other innovation-related matters. It has handled more than 500 different projects since its founding in 2016.

Andrew Sellars, a LAW clinical instructor and director of the Technology Law Clinic, discussed the Voatz case with BU Today Thursday morning.

Q&A

With Andrew Sellars

BU Today: How did the BU/MIT Technology Law Clinic get involved in this?

Sellars: Students who research cybersecurity come to us from time to time asking for help informing the public about their findings. In this case the clinic and our clients knew right away that this was important information to get out to the general public. We wanted to make sure that people were aware of the risks in using this technology, and at the same time we wanted to make sure that if any state was currently using the technology, they had the opportunity to evaluate their use of it and maybe discontinue it or modify it. And we also wanted to make sure that the vendor had an opportunity to respond to the research and fix the problems we identified or explain why it wouldn’t be an issue.

How did you move forward?

We decided to connect to the vendor and election officials through the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, which is a relatively new, freestanding agency within Homeland Security that [was established] in late 2018. Their job is to coordinate security information across the nation for technologies that have important national consequences. We reached out to CISA in mid-January, explaining what we’d found, and through CISA, we were able to arrange conversations with the affected officials and disclose our clients’ findings to the vendor.

Tell us about the flaws they found.

There were a lot of serious problems with this application, including the fact that some of the anti-malware systems that were in this tool could be disabled fairly simply if you either had physical access to the phones or leveraged an exploit [to get into] the operating system. They found that the way the network traffic was configured to transmit the vote to the server meant that you could make some inferences about who the person voted for. The length of the transmission, even though it was encrypted, could give you some insight into who they voted for. These are sophisticated attacks that would require the resources of a large nation-state actor, but these are the American elections, and we certainly know from recent history that foreign governments have incentives to investigate, interfere with, and nudge elections in the United States for their own benefit.

Why does this matter?

We know that hundreds and possibly thousands of votes would be cast through this application over the next year, in pilots serving mobility-impaired voters, forward-deployed military, and with citizens abroad. It’s important that these constituents have the opportunity to vote. I think it’s also important that they have the opportunity to vote securely and with confidence that their vote is being cast correctly. Facilitating that vote through a program that has opportunities for malicious actors to change votes, to leak votes, to see how a person voted, is an attack on the integrity of the voting process.

It’s important that these constituents [mobility-impaired, forward-deployed military, citizens abroad] have the opportunity to vote. I think it’s also important that they have the opportunity to vote securely and with confidence that their vote is being cast correctly.

The present political environment makes that even more important, doesn’t it?

We all need confidence in a fair vote. That’s one of the key tenets of our democracy. We have a vote, we are confident in the results of that vote, and because of that confidence, we treat whoever gets elected as our leaders. And therefore, even if no attack is ever conducted through the application, the potential for these attacks is a serious problem. We have already seen in the 2020 process, which is weeks old, instances where election officials relied on underdeveloped technology, and it completely derailed the Iowa caucuses. That appears to be not a malicious actor, but just bad code. But it shows how even questions about validity can present serious, serious problems. We know this is going to be an extraordinarily contentious election. And we know there are nation-state actors interested in tampering with the results of our elections, and they are actively trying to do so today.

Why did the MIT researchers want to stay anonymous until now?

We had concerns about how the vendor would respond. We were aware of an earlier incident involving research conducted at the University of Michigan, where the vendor, Voatz, treated the research as a malicious act and reported it to authorities, which resulted in the FBI being called in to investigate the researchers. We were concerned about that precedent. We wanted to make sure the work was speaking for itself and there was not any attempt to attack the messenger.

The response from Voatz today was pretty hard-edged.

I am frankly puzzled as to why they are trying to suggest this was somehow self-interested or selfishly motivated. The researchers are highly sophisticated graduate students doing this work for the good of the public. You don’t go to Homeland Security with what you deem to be a critical issue unless you’re quite serious about it. Also, I would note that none of the researchers work with rival companies or in election security generally. They genuinely believe, and have very strong evidence, that this technology should not be trusted. What the vendor doesn’t say is perhaps most revealing of all: they don’t say that they’ve patched any of these vulnerabilities and they don’t say that these vulnerabilities are not real.

This Series

Also in

-

November 7, 2020

Joe Biden Defeats President Trump, Clearing the Way to Becoming 46th US President

-

November 7, 2020

How Does the Electoral College Work and Other Election Questions

-

November 7, 2020

Joe Biden Will Be the Oldest President Elected. Is That Worrisome?

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.