Warren Binford’s Hear My Voice Lets Children Detained at the Border Tell Their Story

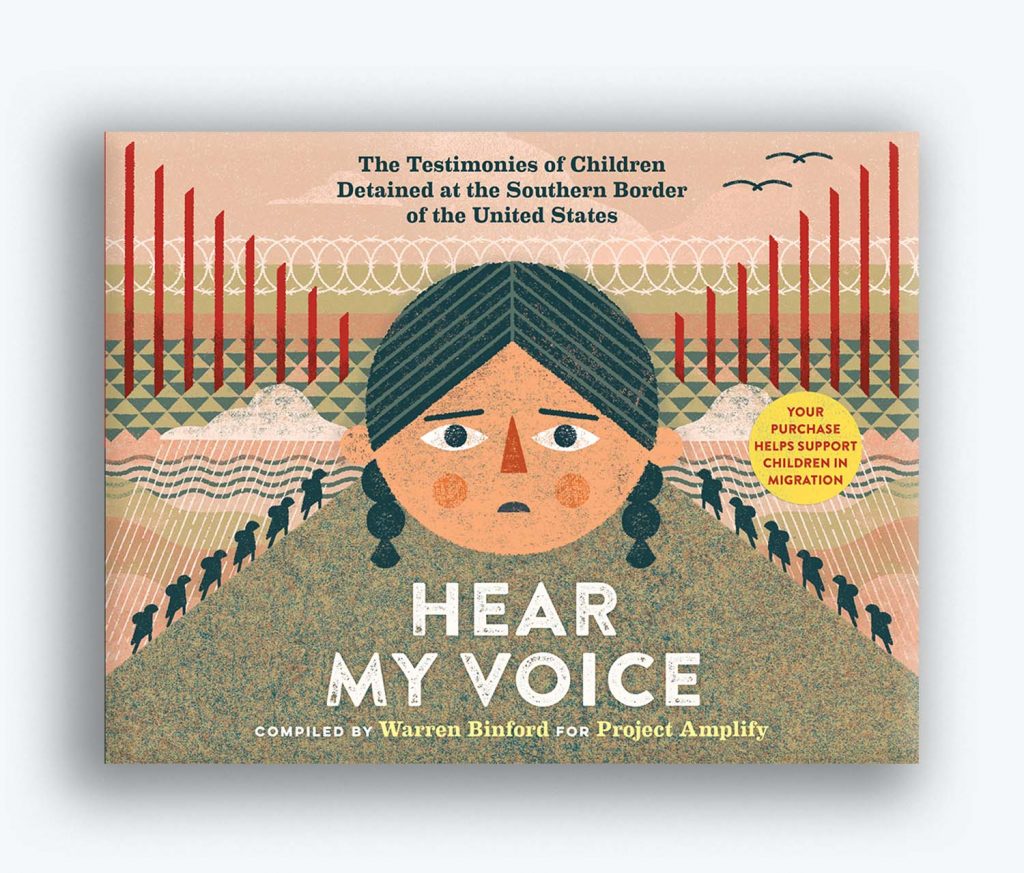

In Hear My Voice, Warren Binford (CGS’87, UNI’89, Wheelock’93) compiles the words of children from Central America held in the US Border Patrol’s Clint Station outside El Paso, Tex. Their sworn accounts, filed in federal court, tell a collective story of harsh reality and inhumane conditions. Photo by Jay Fram

Warren Binford’s Hear My Voice Lets Children Detained at the Border Tell Their Story

Book compiled by the children’s rights advocate and alum features work by 17 Latinx artists

Warren Binford travels the world advocating for children who are trafficked, abused, traumatized, exploited, or forced to migrate because of violence, poverty, or the climate crisis. The international children’s rights scholar shares their stories in expert reports for US courts and international tribunals to help protect their rights. It’s not easy work.

“I try to compartmentalize,” says Binford (CGS’87, UNI’89, Wheelock’93). “I try to be authentic and emotionally present for the child or the parent or other family member while I’m with them, without projecting my own family and experiences onto the situation. If I did that, I would just be a wreck. I try to be very disciplined emotionally, because when I’m not strong, it makes it hard for them to be strong.

“The second thing I do,” she says, “is at the end of my interview or my service to that child: I try to remember that this is their story and not mine. I cannot hold onto their story. It’s not mine and I need to give it back to them.”

Now, she and a team of collaborators are helping a group of those children to tell their own stories, in hopes the world is listening.

In the book, Hear My Voice (Workman Publishing, 2021), Binford compiles the words of 61 children from Central America held in the US Border Patrol’s Clint Station, near the Mexican border outside El Paso, Tex. Their sworn accounts, filed in federal court, tell a collective story of harsh reality, inhumane conditions, and Kafkaesque bureaucracy—all paid for with our tax dollars.

I am from El Salvador. I am from Guatemala.

My little sister and I came from Honduras.

The immigration agents separated me from my father right away.

They took us away from our grandmother and now we are all alone.

I have been here without bathing for twenty-one days.

None of the adults take care of us so we try to take care of each other.

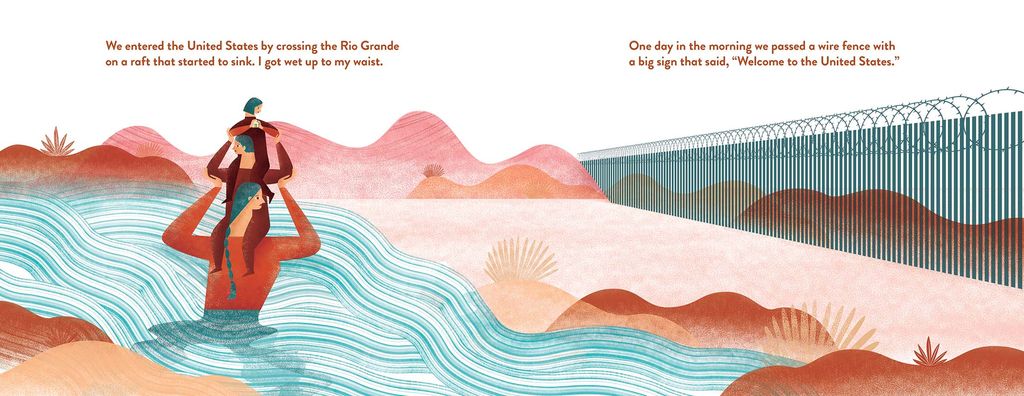

Told in English and Spanish, Hear My Voice/Escucha Mi Voz features illustrations by 17 Latinx artists. Technically it’s a children’s picture book, for ages eight and up, but families will want to read it together.

A Children’s Rights Issue

Immigration has become a highly politicized issue in the United States. But Binford says what happened in Clint and other Border Patrol stations is not a migrant issue, it’s a children’s issue.

She holds the inaugural W. H. Lea for Justice Endowed Chair in Pediatric Law, Ethics & Policy and is a professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, where she works with the school’s Kempe Center for the Prevention and Treatment of Child Abuse and Neglect and the Center for Bioethics and Humanities. She has lent her expertise to the International Red Cross, the International Criminal Court, and many other groups and has served as a court-appointed special advocate for abused and neglected children. Her work also includes studying children’s issues, teaching, training, and lectures.

For several years, she has interviewed children and families and conducted inspections of US government facilities holding thousands of children arriving in the United States from Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Panama, Costa Rica, and Mexico, among other places. She was part of teams of lawyers and translators sent to determine whether the children’s rights were being respected, under a settlement agreement in a federal class action suit brought on behalf of the children. Repeatedly, the site visit teams found systemic mistreatment and neglect of children and families detained by the US Customs and Border Protection, of which the Border Patrol is part.

In June 2019, “we heard from contacts on the front lines that the government was sending kids to the Clint Border Patrol facility, which was strange, because it’s a relatively small, new facility made for 104 adult men,” Binford says. “So we couldn’t figure out where they would be placing kids there. We went there with a handful of people thinking that we might find a dozen or a few dozen kids there, and they handed us a roster with over 350 kids. We said, ‘Where are you keeping these kids?’ They wouldn’t show us. So we said, ‘Bring us the kids, start with the youngest, the ones who have been here the longest, and the child mothers.’

“And they started bringing us these kids, and they were absolutely filthy, dirty, they smelled, they were hungry, they were falling asleep in chairs, on the conference table, they’d just start crying,” Binford says. “We started to ask them what was going on. And that was when we realized that we were in the middle of a crisis, that another kid could die.”

Some of the children were so traumatized they wouldn’t even speak, says Michael Bochenek, senior counsel for the children’s rights division of Human Rights Watch, who was with Binford at the Clint facility and many other site visits since 2018.

“The lights were on 24 hours a day, there were a lot of slamming doors and shouted commands, and the kids are understandably terrified, and they haven’t, in most cases, contacted parents or family members,” Bochenek says. “There were teenage girls taking care of a four-year-old who was unrelated to any of them. The guards had just said, ‘Who can take care of this baby?’

“It was, in every respect, just a horrifying kind of thing,” he says.

They interviewed children for 10 hours until the guards kicked them out, Binford says, and then they drove around the perimeter of the facility to try to figure out where the 352 children were kept. “We found this newly erected corrugated metal building, like a warehouse, in the desert. And it was like, oh my God, that’s where I think they’re keeping the kids. And there were tents out in the desert too.”

The next day they asked the children to draw pictures of where they were being kept, and the pictures matched what they had seen from outside the fence.

When they reported back to the children’s attorneys, they were advised to go to the media, the first time that has happened, Binford says. The story quickly exploded. “Trump went on Twitter and basically said this was fake news and I was lying,” she says. Vice President Mike Pence flew to Texas for a photo op at another facility. It was clear to Binford that there was a long struggle ahead.

“We said, we need to recenter this on the truth and recenter this on the children,” she says. One way they did that was to set up a pop-up nonprofit, Project Amplify, to try to raise up the voices of the children and help tell their stories. The first step was to make the children’s testimony easily and publicly available online. In the months since, the nonprofit also offered artist exhibitions inspired by the children’s testimonies, as well as concerts, lectures, videos—and the children’s book.

Hear My Voice was released in April, quickly topping several Amazon categories and requiring a second printing. Publishers Weekly gave it a starred review, calling it “a heartrending but vital work.”

“The whole purpose of Project Amplify was to push back on this false narrative that the administration was putting out and establish the historical truth of what was happening to these children,” Binford says. “We don’t just have the privileged advocate for these children; we make space for them to tell their stories and advocate for themselves, and we support them in that.”

“A Force of Nature”

Binford “comes with a whole host of skills you don’t appreciate until you see how she sits down and works with children,” says Bochenek, who wrote the foreword to Hear My Voice. “To put children at ease and elicit information without coercion, to make it participatory, is amazing to watch. She’s a force of nature.”

Binford grew up in Los Angeles attending private schools; community service projects brought her in contact with historically disadvantaged groups. “I was shocked by the disparities between their lives and my own, so even as a teenager, I started working as a summer camp counselor for L.A. parks and rec in a Hispanic community,” she says.

Known as Wendi when she arrived at BU in the 1980s, she became active in student government, which led to an early media appearance: debating dormitory rules with then–University President John Silber (Hon.’95) on The Phil Donahue Show. She must have impressed him, because he asked her to work on his ultimately unsuccessful 1990 campaign for Massachusetts governor, and after the election, in the BU president’s office.

She also taught in underserved communities of Chelsea, Mass., and London while she earned a Master of Education in early childhood education at what is now BU Wheelock College of Education & Human Development. She received her law degree from Harvard.

Most of the children were transferred out of Clint when the controversy erupted, but even the new administration is hardly transparent about where kids are kept, Binford says. Since the start of the pandemic, the government has tried to block all in-person site visits for public health reasons.

But the problem isn’t going away. “A lot of people don’t understand that with the climate crisis, human migration is going to increase significantly,” Binford says.

That means her advocacy work to educate the public and try to tell the children’s stories continues. And despite the government’s efforts, teams are still making their difficult site visits.

During those visits, Binford keeps her feelings contained, as professionals do, but that only works for so long, she says: “I get on the plane and just cry, sometimes all the way home.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.