Leslie Epstein’s “Novel of War and Celluloid”

The climactic scene from the 1942 Oscar-winning film Casablanca: Conrad Veidt (from left) Claude Rains, Paul Henreid, Humphrey Bogart, and Ingrid Bergman. Photo by FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives via Getty Images

Leslie Epstein’s “Novel of War and Celluloid”

BU prof, whose father and uncle wrote the Oscar-winning Casablanca, takes a fictional look behind the scenes

Leslie Epstein’s new novel is a behind-the-scenes Hollywood comedy involving his father and uncle, real-life Hollywood screenwriters. It’s also a scathing look at 1940s global realpolitik, from the terrible machinations inside Hitler’s Third Reich to scenes of FDR, Churchill, and Stalin mixing wisecracks and threats in summits and screenings alike.

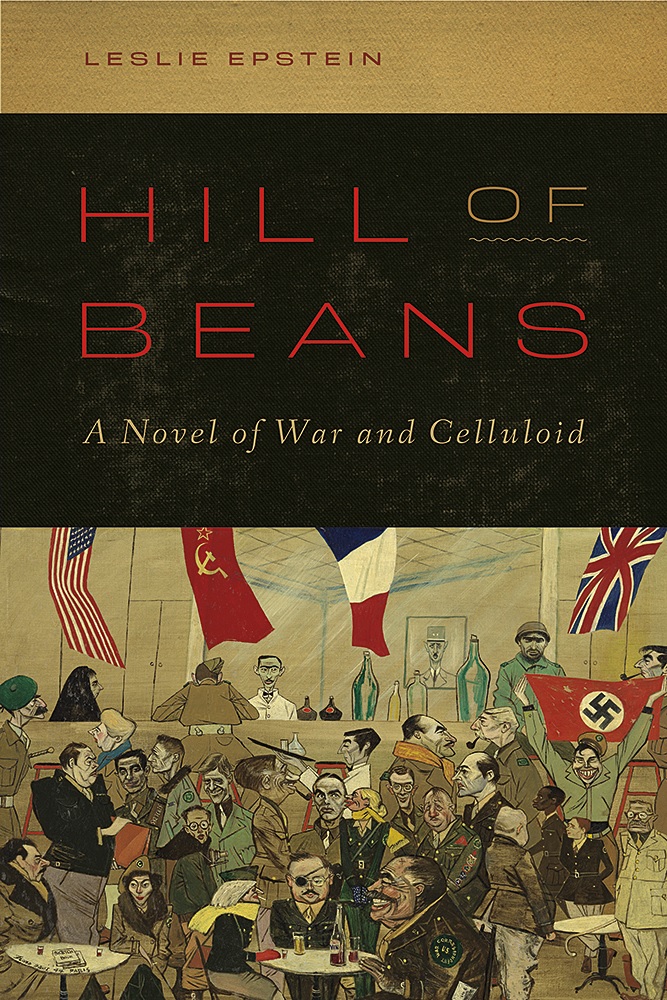

Hill of Beans: A Novel of War and Celluloid (University of New Mexico Press, 2021) is the 12th novel by Epstein, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of English, who ran the BU Creative Writing Program for more than 30 years. It centers on (fictional) efforts by real-life movie mogul Jack L. Warner to stage-manage the Allied invasion of North Africa in 1942 to help make a splashy opening for the Warner Bros. film Casablanca.

“Jack is not one-dimensional,” Epstein says. “He’s terrible, but he’s also kind of wonderful. They say this happens with authors: I grew kind of fond of him, even though I could see him clearly.”

Epstein will discuss Hill of Beans with author and film critic A. S. Hamrah during an online event with Brookline Booksmith Monday, March 1, at 7 pm. The event is free and open to the public.

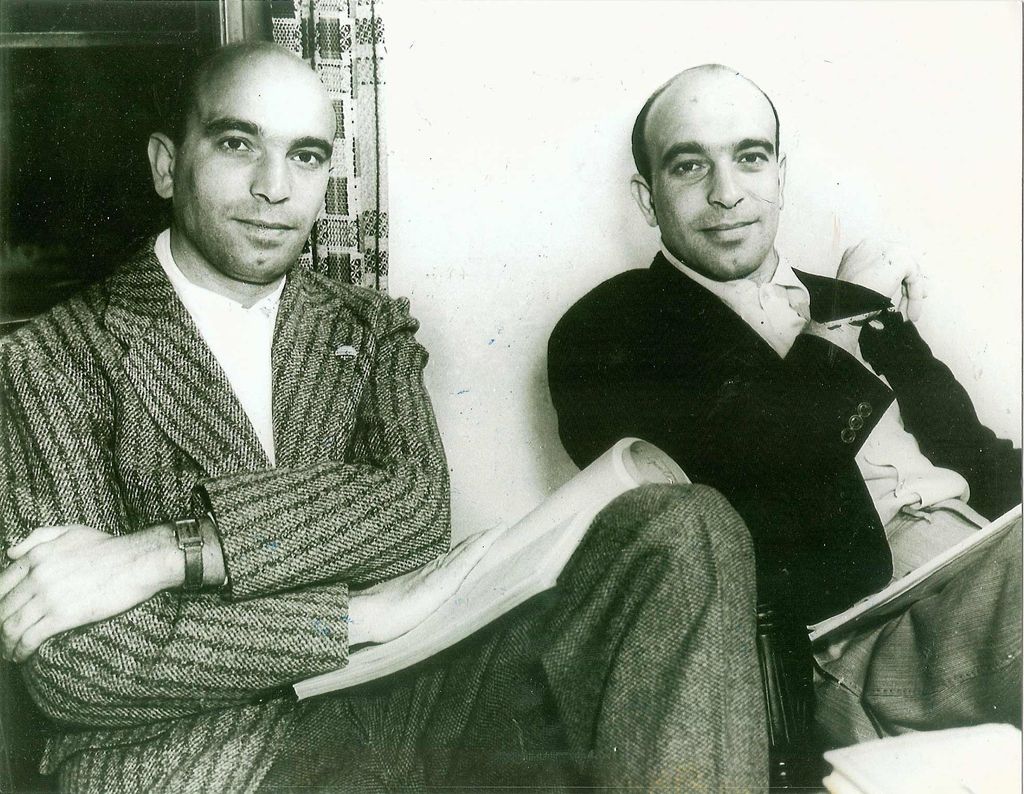

Epstein says the novel, a decade in the works, is a culmination of subjects and themes that have figured in his previous books. He has delved into World War II and the Holocaust (King of the Jews) and his own Hollywood upbringing (San Remo Drive). Hill of Beans features appearances by the Führer himself and by Epstein’s father, Philip G. Epstein, and uncle, Julius J. Epstein, the team who won Oscars for writing Casablanca. It’s a vast tragicomedy darting between Berlin, Washington, Los Angeles, Casablanca, Moscow, and many other points on the globe, and Epstein says it took a lot of work to put it together.

Hill of Beans: A Novel of War and Celluloid is Leslie Epstein’s latest book. Photo by Ilene Epstein

“Years of research. Going out to California, to the Motion Picture Academy library and the University of Southern California library for a lot of the old film stuff,” he says. “Our own wonderful music librarians at BU and others at Mugar Library. Lots and lots of books.” And there’s a lot in the book that’s real: passages from Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels’ diaries, Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper’s columns, General George Patton’s notebooks, and, he says, “Jack Warner’s actual gags, my father and uncle’s actual gags.”

“But there’s also of course, imagination at play I hope,” Epstein says. “Jack Warner finagling, begging, blackmailing, cajoling, forcing people like FDR, Stalin, Churchill, the whole crew, to make sure that the invasion of Morocco in 1942 took place just when he was going to premiere his new movie, Casablanca.”

Generally acclaimed as one of the greatest films of all time, Casablanca stars Humphrey Bogart as Rick, an American expatriate nightclub owner in the Moroccan city, then controlled by Vichy France. When his lost love, Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman) arrives in town, fleeing the Nazis with her Czech resistance leader husband (Paul Henreid), intrigue and bittersweet romance ensue.

In real life, Warner hoped publicity from the Casablanca summit meeting between FDR and Churchill in 1943, after the Allies’ invasion of North Africa, would help his movie. In Epstein’s book, Warner is such a blustery, egomaniacal, funny, tough, nasty presence that he emerges as the dominant player even in a cast that includes the aforementioned world leaders as well as Patton, Goebbels, Hopper, and film cut-up Harpo Marx. An accurate portrait?

“It’s darn close,” Epstein says. “My father and uncle had a decades-long feud with Jack Warner, and a lot of the language he uses and they use is language that I knew through my uncle Julie. I did a lot of research on Warner. He was a terrible man, no question about it, and a man of his times—more than a man of his times! He was a misogynist, a racist, a bully.

“But also, the great discovery for me was, the more I read, the more I came to have a kind of grudging admiration for him,” Epstein says. “First of all, the sheer energy and perseverance, sexual and otherwise, that he displays. And also the courage he had to follow a kind of vision. For example, when Goebbels insisted that every Hollywood studio fire its Jewish employees in Germany, they just did it. Jack Warner was the only one to say, ‘Hell no, I’m closing my office there.’ He gave up those profits, and he cared a lot about profits. Paramount stayed, to its shame, until Pearl Harbor.”

Non-famous members of Epstein’s cast include Abdul Maljan, aka the Terrible Turk, an ex-boxer who was Warner’s masseur and perhaps his only real friend, and Karelena Kaiser, a German actress whose tragic story touches nearly all of them.

Today’s readers, accustomed to ellipses instead of epithets, may be taken aback by what Epstein says is an historically accurate barrage of religious and racial slurs, sexist comments, and filthy jokes, spoken by Warner and many of the other players. He is not one to sweat the reaction this will get. “I know I’ll lose a large audience and get a lot of criticism,” says Epstein, rolling his eyes a bit at today’s speech codes. “But I believe in art, and I believe in the imagination.”

He notes that many of his students today have never even seen Casablanca. “It impoverishes them, of course,” he says. “In all of my teaching at BU, I make them watch two great movies every semester, and I send them to great music, and I send them to the MFA, because a lack of beauty in their life leads to this shriveled imagination.” Googling the cultural references they may not know may help them understand why he wrote the words they will find offensive, too. “If they look up Patton, they’ll find his own words.”

Philip and Julius Epstein come off as witty, darting presences in the story, mainly notable at first for enraging Warner by starting their workday at the studio after lunch. In real life, the two men get most of the credit for the Casablanca script, which was based on Everybody Comes to Rick’s, an unproduced stage play by Murray Burnett and Joan Alison. But they shared the best adapted screenplay Oscar win with Howard Koch, who worked on the film for a few weeks when the Epsteins temporarily left for another project and sometimes later exaggerated his role.

Bostonians also know Epstein as the father of Theo Epstein, a baseball executive who helped both the Red Sox and the Chicago Cubs win the World Series this millennium. He has two other children, Paul Epstein, a high school counselor in Brookline, and Anya Epstein, a screenwriter and TV showrunner.

And where is his late father’s Oscar? Epstein says that he had it until last July: “I gave it to my daughter for her 50th birthday. I have a photo of it instead.”

Event Details

Leslie Epstein Launches Hill of Beans with A. S. Hamrah

Discussing his new novel with author and film critic A. S. Hamrah

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.