Pandemic Introduced Americans to Parks and Open Spaces and Trend Will Continue, Say US Mayors

The 2020 IoC report conclusion: the value of parks and open spaces, which offer sanctuary and solace and provide forums to protest racial injustice throughout the United States, has been underappreciated.

Pandemic Introduced Americans to Parks and Open Spaces and Trend Will Continue, Say US Mayors

BU Initiative on Cities survey: city leaders expect new appreciation of outdoors to last

Over the past year, as COVID-19 restrictions shuttered restaurants, museums, and sports events, Americans sought comfort, as well as escape from their living rooms, in public parks and open spaces. In Erie, Pa., the number of visitors to Presque Isle State Park soared 165 percent during the third week of March 2020, compared to the same week one year earlier. That same month, popular trails in Dallas saw usage increase from 30 to 75 percent, and trails in Minneapolis saw summertime levels of visitors during the still-cold month. At the same time, many cities encouraged residents to step outside; they created new space for outdoor dining, widened sidewalks, and laid out new bike lanes and bike paths.

It’s a small perk, but the pandemic, which has killed more than half a million Americans, compelled many people to become better acquainted with the outdoor spaces in their metropolitan area. This newfound relationship is generally considered to be healthful for people, and for their communities. But will that marriage last? Or, when the pandemic abates, will people forgo outdoor spaces in favor of Netflix? Will cities eliminate the bike paths and push restaurant diners back indoors? Last summer, Boston University’s Initiative on Cities put those questions and others to 130 mayors of American cities with more than 75,000 residents. The answers in the latest Menino Survey of Mayors, released March 31, suggest most mayors have faith in the marriage, at least for now.

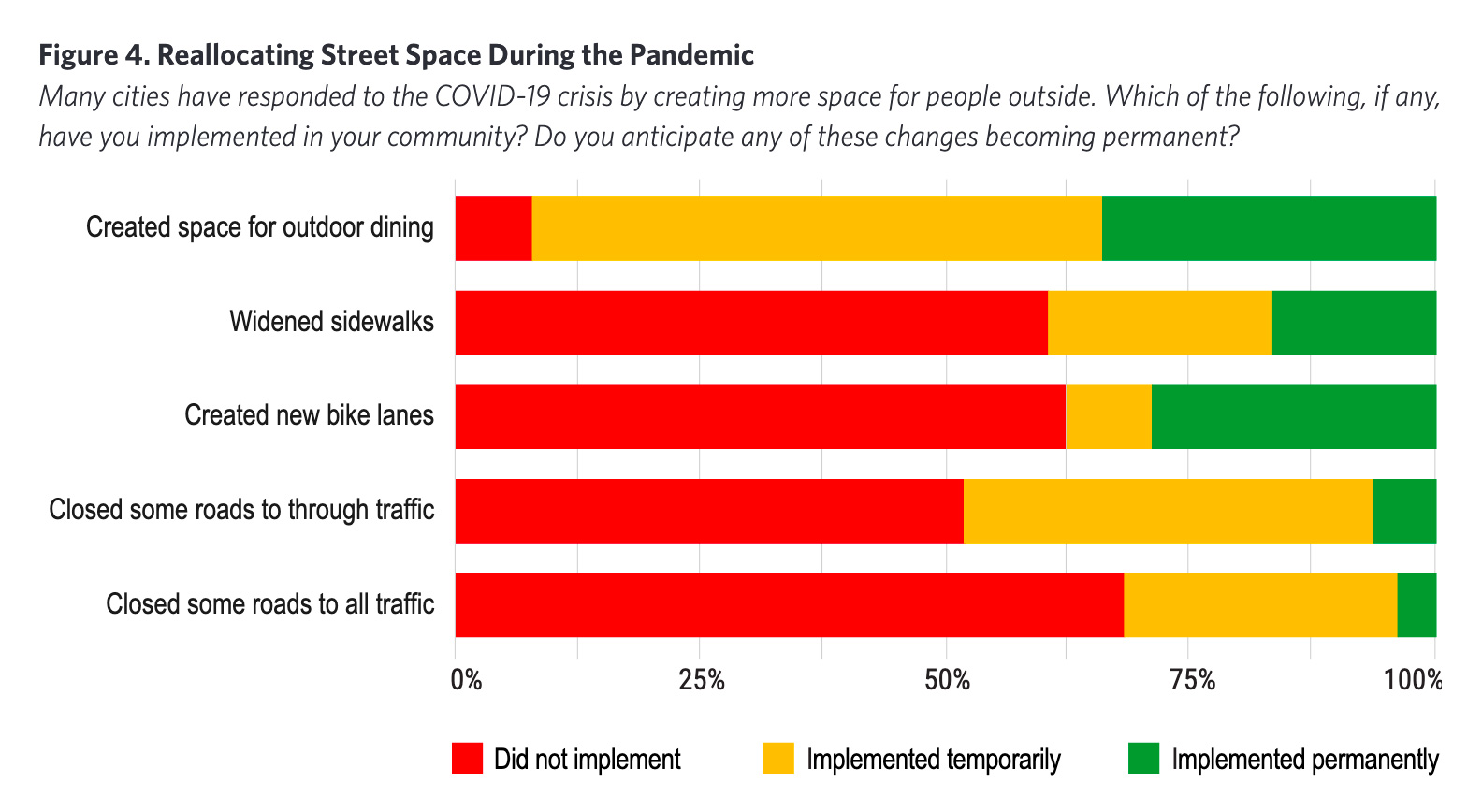

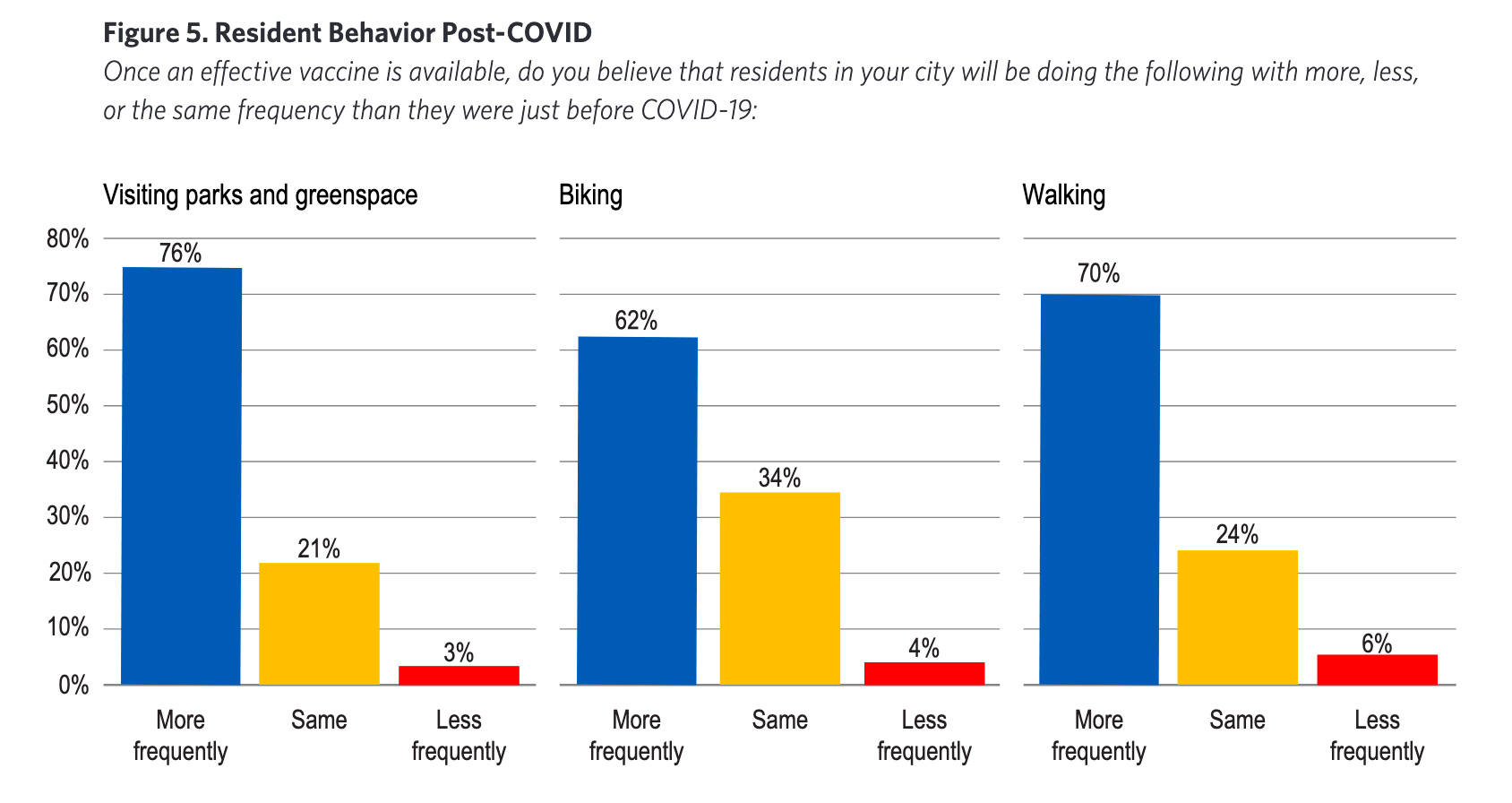

Three out of four mayors surveyed said they expect residents to continue spending more time visiting parks and greenspaces than they did before the pandemic, and roughly two-thirds said they expect residents to spend more time biking or walking. More than half of the responding mayors said they would like to see more improvements to their parks and to programming events within those parks, although more than a third also said they expected funding for parks to take a big financial hit in the wake of the pandemic. And while nearly half of the mayors said they had shut down some roads to through traffic, only 6 percent said they planned to make the closures permanent.

The IoC report on the survey, titled Urban Parks and the Public Realm: Equity & Access in Post-COVID Cities, found that in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, many cities across the country closed parks, playgrounds, and hiking trails, hoping that shutting down outdoors spaces would also shut down the spread of the virus. That changed, however, when health experts realized that the outdoors offered one of the safest places to be. Cities moved quickly to reopen parks and close streets to allow people to play and safely gather. Communities also offered broad support for protesters who gathered in record numbers last summer to call for racial justice in the wake of recent police violence against Black Americans.

The report was written by Katharine Lusk, BU Initiative on Cities codirector; PhD political science candidate Songhyun Park (GRS’23); Katherine Levine Einstein and David M. Glick, both College of Arts & Sciences political science associate professors; Maxwell Palmer, a CAS political science assistant professor; and Stacy Fox, IoC associate director.

“This past year reminded mayors and their constituents that the public realm can really be the people’s realm,” says Lusk, the report’s lead author. “Cities wrote new stories on their streets and in their parks—of people marching, kids playing, families dining.

“Our survey showed that it’s possible to reclaim the public realm for people,” she says. “Nine out of 10 mayors created new space for outdoor dining, which meant reclaiming parking lots, on-street parking, or—in some cases—entire streets. This reallocation required changes to zoning, new permitting processes, new inspectional services, and mayors moved swiftly.”

Key findings

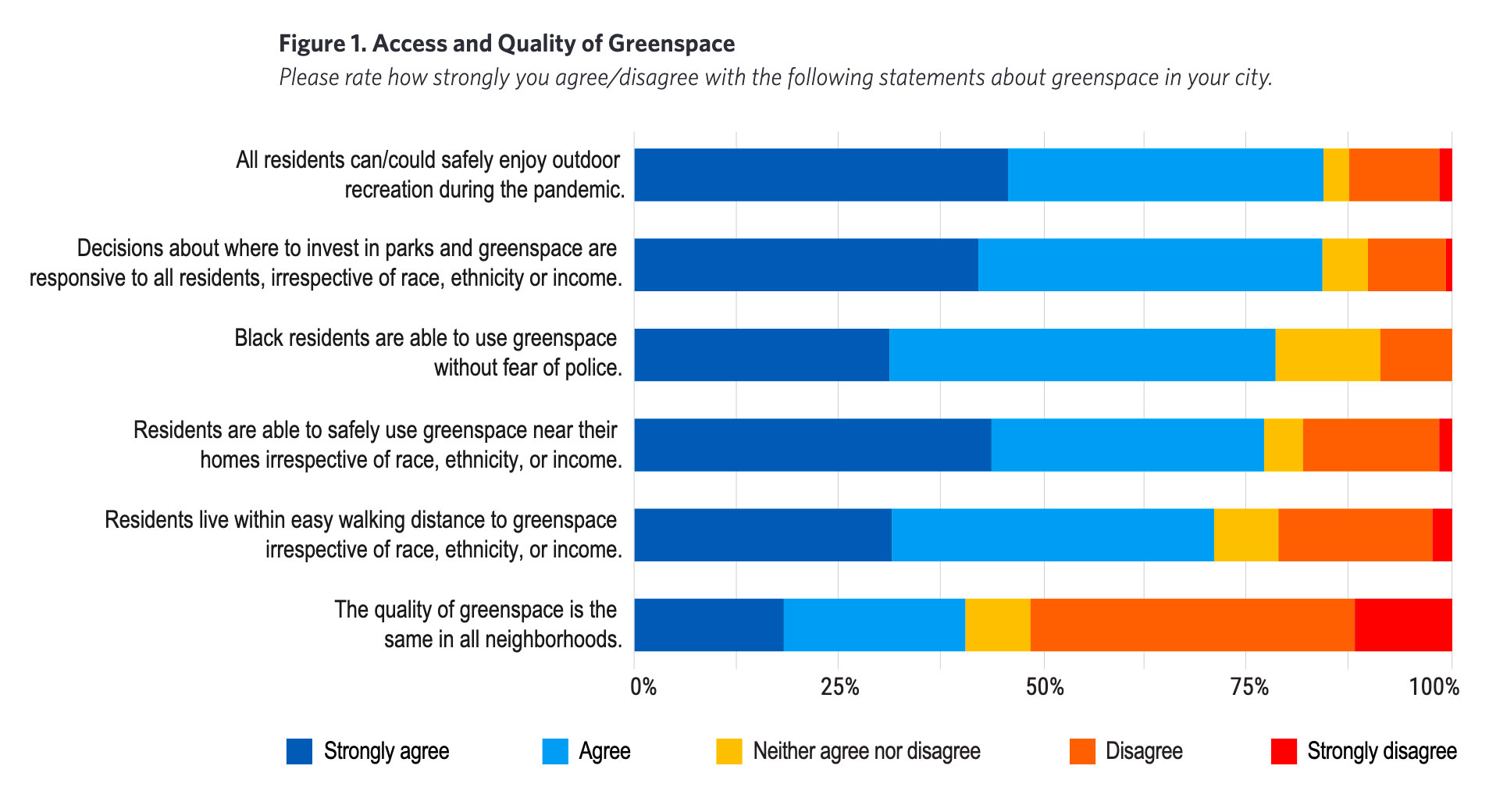

Across the country, mayors tend to paint a very positive picture of their parks and open space. They consider their parks to be widely accessible and safe to use. Many spoke of their parks with pride; 70 percent agree that all residents, regardless of race, ethnicity, or income, live within easy walking distance of a park. A slightly higher proportion, 77 percent, believe that parks are also safe for all users, and a similar percentage believe Black residents, specifically, are able to safely use parks without fear of police. Yet less than half of responding mayors said the quality of greenspace was the same in all neighborhoods.

Research from the Trust for Public Land, which, along with Citi and the Rockefeller Foundation, supported the research, shows that parks serving primarily nonwhite populations are half the size and serve five times as many people as parks that serve majority white populations.

“I think both the most encouraging and discouraging finding is the juxtaposition of the question about residents having equal access to open space and having open space of equal quality, “says coauthor Glick. “The fact that mayors differentiate the two is encouraging and offers the potential for change. The fact that the gap is so large, and was so large at a time when such spaces were especially important, is discouraging.”

Lusk says she found the parks’ “access vs. quality” distinction surprising. “Residents in the Northeast are most likely to have easy walk access to a park,” she says (79 percent of mayors agree), “but mayors in the Northeast are most likely to acknowledge the quality of parks and greenspace varies by neighborhood” (69 percent agree).

The survey’s findings suggest that most American mayors have not embraced the pandemic as an opportunity to fundamentally reimagine how they allocate space in the public realm, particularly roadways. “Dining was the only area where rapid street innovation was widespread,” says Lusk. “In Europe, the rapid expansion of new bike infrastructure–which we did not see in the United States–had a positive impact on cycling behavior.”

The relatively modest ambitions of US mayors run counter to results from prior surveys. In 2018, mayors told the IoC that they believe traffic crashes are the public health issue they’re held most accountable for, providing motivation to create safer streets. And in the 2019 survey, 76 percent said they believed that their cities were too oriented towards cars, and 71 percent favored giving up parking and driving lanes to create new bike lanes.

Asked about residents’ future use of local greenspaces, most mayors were optimistic about a continuing appreciation for local parks and a lasting interest in biking and walking. Mayors in Northeast cities were most likely to expect their residents to increase visiting parks (84 percent), walking (84 percent), and cycling (74 percent).

The IoC found that even while most mayors are seeing budgets shrink, they are taking on new responsibilities. In December 2020, prior to the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, the National League of Cities reported that cities and towns had seen revenues decline by 21 percent since the beginning of the pandemic, while expenditures have increased by 17 percent as a result of it.

Asked where they anticipate the most “dramatic” financial cuts to local services, mayors most often cited schools, with parks coming in second. The IoC reports that on average, big cities spent about $250 per resident on parks and recreation and natural resources in 2017. That same year, elementary and secondary education investments averaged $1,930 per resident, and police expenditures averaged $410.

The IoC report concludes that the last year surveyed has revealed the long unappreciated value of parks and open spaces, which offer sanctuary and solace and provide forums to protest racial injustice throughout the United States. “But,” the authors write, “more remains to be done to create public spaces that are welcoming, accessible, and safe to all residents, and that promote both human and ecological health. Our interviews with mayors revealed many who are already advocates for high-quality greenspace in every neighborhood, and many more who have not yet realized that these are true legacy investments. We also heard from relatively few mayors who sought to permanently reclaim streets for new human-centered, multigenerational uses. As the country emerges from this winter, perhaps mayors—and their constituents—will look to the public realm with fresh eyes and ideas.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.