Two Ways of Exploring Visual Narrative

Dana Clancy (CFA’99), director of the CFA School of Visual Arts, has been making narrative art of her own while prepping a new MFA program in Visual Narrative. Photo by Cydney Scott

Two Ways of Exploring Visual Narrative

Dana Clancy, School of Visual Arts director, preps a new MFA program while painting her pandemic experience on New York Times pages

People pick up the Sunday New York Times to read the front page or the Book Review, to mock the glitzy wedding announcements or tackle the crossword. But over the last year of pandemic and political tumult, Dana Clancy has been picking it up looking for pages to paint on.

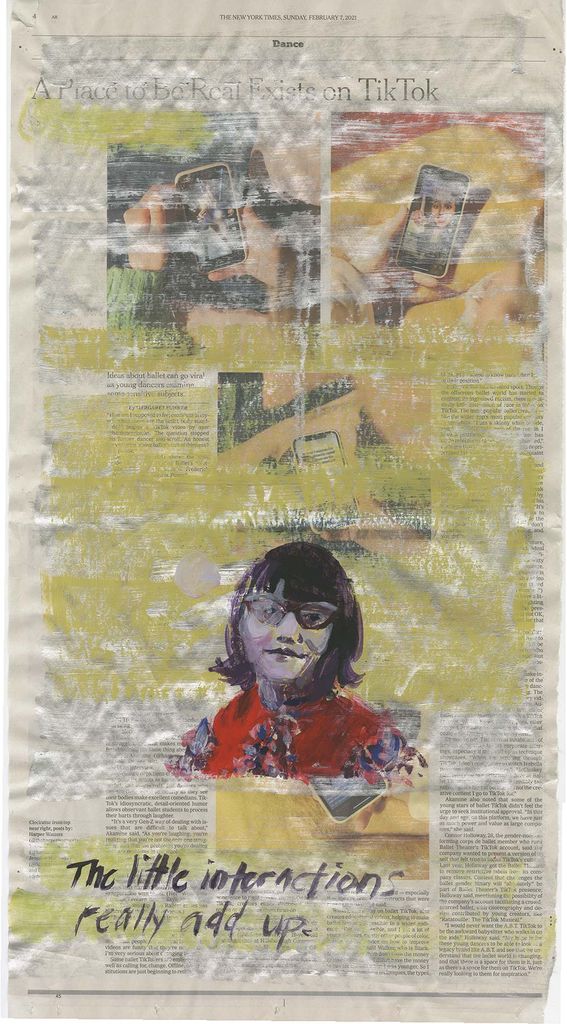

“I paint only on the Sunday New York Times, keeping or covering the news as the week unwinds in unexpected, often shocking ways,” says Clancy (CFA’99), the director of the College of Fine Arts School of Visual Arts and an associate professor of art. She paints over part or all of each chosen page with blocks of color, adds portraits of people she’s Zooming with, then adds words, usually things those people have said. “Those words written over weeks of news came to feel like a shared public space—the kind of space I’m missing and want for all of us,” she says.

Begun in September 2020 and now planned to last a year, the project has the working title Breaking News/Broken Year.

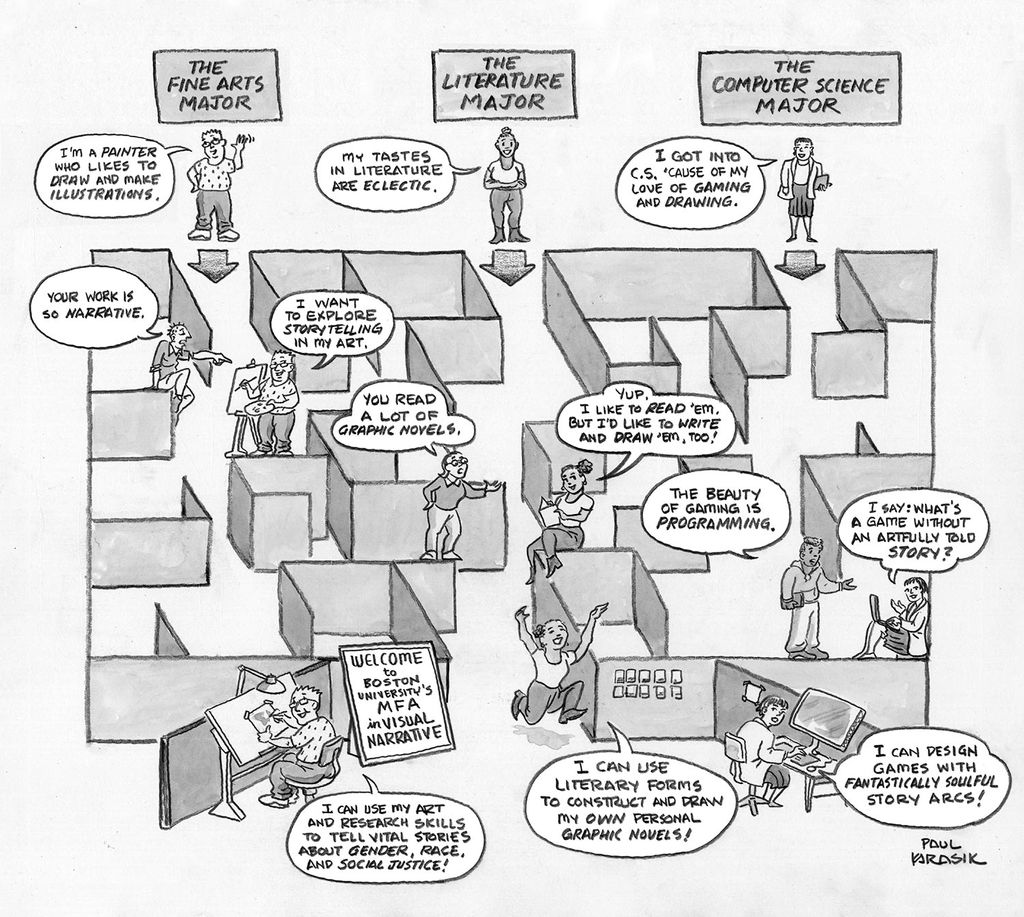

It is also, in a way, part of her preparation for the September 2022 launch of a new CFA Master of Fine Arts program in Visual Narrative, which will integrate fine arts with sequential art storytelling practices, both written and visual. The first year will focus entirely on nonfiction, but in the second year, students’ thesis projects could be nonfiction, perhaps from a collaboration with the BU Center for Antiracist Research or the School of Medicine, or fiction, from a animation informed by a required motion graphics course to a graphic novel like Alison Bechdel’s 2006 best seller Fun Home.

“In recent years, CFA alumni have become leaders in visual narrative—from the Oscar-winning producer responsible for Frozen to artists whose medical illustrations reveal the truth of crime scenes,” says Harvey Young, dean of CFA. “This new program supports the ambitions of smart, talented, creative artists and mentors them along a variety of possible pathways: animated storytelling, graphic novels, medical humanities, and more.”

Students have been asking for this, Clancy says. “Sometimes they called it illustration, sometimes they called it digital drawing.” When she visited the Serious Comics class taught by Davida Pines, a College of General Studies associate professor and chair of rhetoric, narrative was a big part of the discussion. She planned the new degree in collaboration with Young, SVA faculty, and others, notably Paul Karasik and Joel Christian Gill. Karasik, a CFA lecturer, has published cartoons in The New Yorker and is best known as cocreator, with David Mazzuchelli, of the lauded graphic novel adaptation of Paul Auster’s novel City of Glass. Gill (CFA’04) an acclaimed cartoonist, author, and associate professor of illustration at Massachusetts College of Art and Design, is working on a graphic novel adaptation of the best seller Stamped from the Beginning by Ibram X. Kendi, BU’s Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities and founding director of the Center for Antiracist Research.

“A lot of people, when they think of comics, they think about the floppies [traditional comic books] we see on a monthly basis, the superhero stories that are basically Michael Bay films in narrative form,” says Gill. “But over the last 15 or 20 years, people have come around to the idea that comics—that is, visual narrative—is just a mode of creation, not a genre.

“When you start digging into the scholarly information about comics as literature or comics as a theory of making visual images in a story form,” he says, “you get to a deeper understanding of how we at a base level connect with images.”

More than a year out from the first classes, there’s already a lot to do, including recruiting students (applications are due in January) and hiring an associate professor to oversee the program (interviews will be held this fall). The multiyear process has already included passing muster with accreditors and the University.

“It was an organic thing. Students were looking for it. We wanted to look for some degrees that would connect our existing programs,” Clancy says. “And these leaders in the field said, hey, let’s talk about comics in narrative format as being a powerful way to tell marginalized stories and stories of conflict.

“I think we really saw over this last year how narrative can spur people to action, whether it’s awful action or really important action,” she says. “The role of narrative and visual narrative feels more and more important.”

Her back pages

Clancy says thinking about the new major no doubt fed into her own project. So did the job of director during the pandemic, opening for in-person classes while keeping students safe—“I am so proud that SVA kept almost every studio course going with in-person components for students on campus,” she says. But the biggest influences may have been the juxtaposition of fear, anger, and loss with the drumbeat of news about COVID, the 2020 presidential election, and the ongoing racial reckoning in America.

On a recent morning, Clancy taped dozens of the painted pages to the bare white walls of an empty fifth floor studio at 855 Comm Ave, the first time she’d been able to see so many all together. The faces of friends and coworkers dotted throughout can seem like a respite, an oasis, but they cannot really be separated from their chaotic surroundings on the page.

When it started, Clancy was painting and talking over Zoom with her regular Sunday crew of artist friends, a decade-old critique group that also became a weekly social outlet during the pandemic. She spread out pages of the paper under her computer to protect the table as she painted, and one day quickly did a little portrait on it of one of the faces on her computer screen. A light bulb went on.

The project officially started last September 6, and Clancy quickly got into a rhythm, working with water-based paint, mostly acrylic and gouache. She’d prep a few pages with color before the group meeting started—she consistently used the Times’ weekly “Tracking the Pandemic” page—then finished one during the Zoom session. Other pages she’d prepped would get used during Zoom meetings on other days of the week.

![One of Dana Clancy’s painted pages of the New York Times. It features a portrait of a black woman with glasses and earrings and some text painted on that reads “Change space or create space…[NARRATIVES]….October 13, 2020…. We need to privilege artists who are black and brown…”](/files/2021/07/resize-16_WBURBlackArts-559x1024.jpg)

Clancy’s work is painted over pages of the Sunday edition of the New York Times and features portraits of, and words from, her friends and fellow artists as she saw and heard them over Zoom during the pandemic. Individual images courtesy of Dana Clancy; photo by Cydney Scott

“If I was sitting there talking with another artist, and we were both making something in the studio at the same time,” Clancy says, “it was more natural and even created a sense of intimacy despite the digital distancing of Zoom.”

Here and there a headline or a paragraph of text breaks through. But the words painted on the page come from the person pictured or document a group conversation—quotes that range from oracular to stressed-out. “Words and pictures have to work together” is from a workshop for SVA students led by Gill. From sculptor and critique group member Audrey Goldstein, former chair of the Suffolk University art and design department: “When you’re picking up humans you use your body as a fulcrum.” We’ll leave anonymous the voices behind this exchange: “How are you doing /I don’t know.”

Normally Clancy paints in oil on wood panels, and it can be a long, slow, painstaking process.

“It takes months to make a painting, and I don’t show it until it’s done,” she says, taping another Times page to the wall. “This is a very different project for me. These are hasty, they’re made between meetings and at meetings. It’s me trying to capture a truth about the year. I think the sum of the parts is more what they’re about than the individual drawings. The fragility is part of it.”

Is that new way of working freeing or frightening?

“Both. It feels right for this year.”

Find required courses, learning outcomes, and other details of the MFA in Visual Narrative here.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.