Peter Guralnick (CAS’67, GRS’68) Says Looking to Get Lost is as Close to a Memoir as He’ll Ever Write

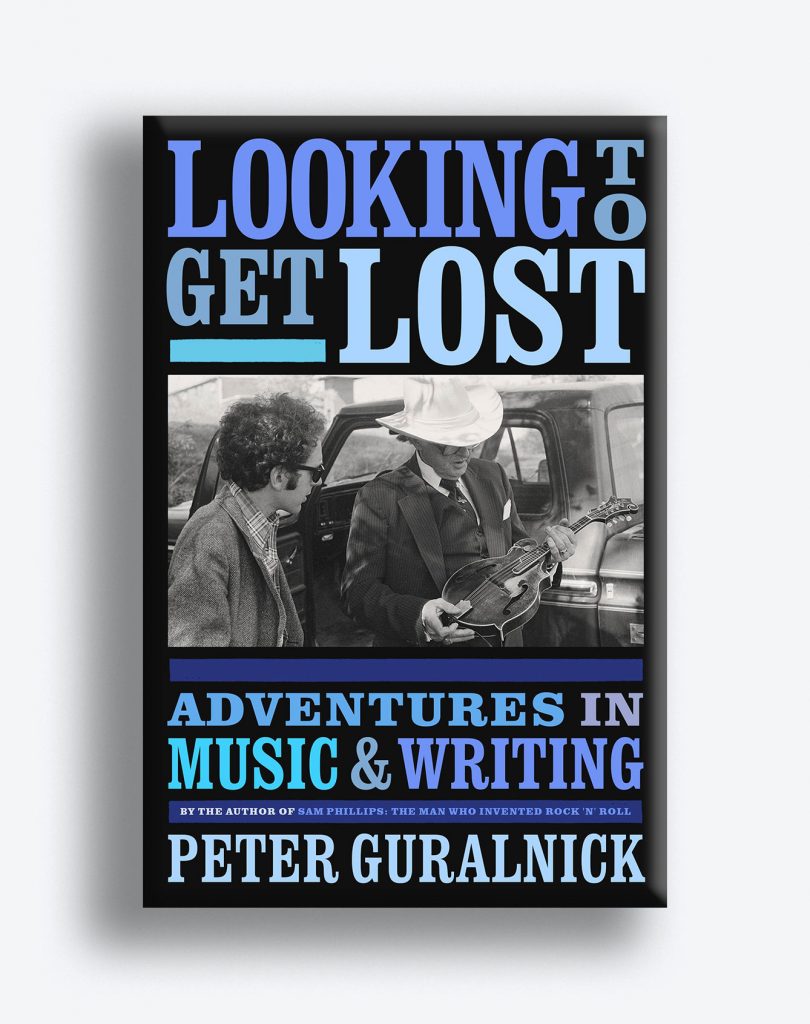

The book is a collection of new and rewritten pieces on “people that I knew, people that I cared about, some I knew better than others,” says Guralnick. Photo by Mike Leahy

Peter Guralnick (CAS’67, GRS’68) Says Looking to Get Lost is as Close to a Memoir as He’ll Ever Write

Collection focuses on favorite artists, including Ray Charles, Merle Haggard, and country singer Dick Curless

The life’s work of writer Peter Guralnick is a deep, deep dive into American popular music of the mid-20th century: blues, soul, country, and the first generation of rock ’n’ roll. From his 1970s collections Feel Like Going Home and Lost Highway: Journeys and Arrivals of American Musicians to his monumental two-volume biography of Elvis Presley in the 1990s to books on Sam Cooke and producer Sam Phillips, he’s chronicled the artists who emerged from the juke joints and honky-tonks to change the world.

Now, the Massachusetts native unveils Looking to Get Lost: Adventures in Music and Writing (Little, Brown and Company, 2020), a collection of new and rewritten pieces on Robert Johnson and Tammy Wynette, Willie Dixon and Chuck Berry, Ray Charles and Merle Haggard, as well as less famous players like Maine-born country singer Dick Curless.

“As the book evolved, it became more and more evident to me that it was the story of my life,” Guralnick says. “In choosing the pieces I wanted to include, it was like having a party for all my friends. That’s how I felt about the people in it, people that I knew, people that I cared about, some I knew better than others.”

Guralnick (CAS’67, GRS’68) long intended to profile Curless, who achieved a certain level of success but never the kind of fame commensurate with his talent. The poignant 70-page piece that finally emerges here, “Dick Curless: The Return of the Tumbleweed Kid,” by far the longest in the book, is based on Guralnick’s usual copious research and personal connection. That the two first met decades ago at an Amesbury, Mass., truck stop, where they were introduced by rockabilly legend Sleepy LaBeef, is typical Guralnick too.

Guralnick calls this “a book about creativity,” and he focuses on how artists made breakthrough recordings or clung to their individuality throughout a career. The piece on Ray Charles examines how cutting loose on a single song (“I Got a Woman”) in the recording studio changed the course of his career and perhaps the trajectory of pop music.

“Two things struck me that the people I was writing about had in common. First, the work ethic,” he says. “People can talk all they want about the lives they led, about how Waylon Jennings and Johnny Cash wrecked hotel rooms at certain points in their life, but their work belies that this was their intent. Where they were in their hearts was in the work they did, and they remained committed to that.

“As the book evolved, it became more and more evident to me that it was the story of my life. In choosing the pieces…it was like having a party for all my friends. That’s how I felt about the people in it, people that I knew, people that I cared about.”

“The other thing was the democratic perspective they had, not politically, but each and every one of them had their ears wide open. They were open to any kind of influence. You could say that about Bob Wills, you could say that about Bing Crosby, or Elvis or Jerry Lee Lewis or Howlin’ Wolf. They were hearing everything. They were open to every kind of thing.”

The book also finds Guralnick writing more personally than usual, about his long and complicated friendship with soul singer Solomon Burke, and how his grandfather’s influence helped make him a writer. Guralnick majored in classics as an undergraduate, earned a master’s in creative writing, and taught classics at BU from 1967 until 1973. He recalls clearly the moment he knew writing was his life’s work, “although my kids have told me never to use the word ‘epiphany’ again, so I won’t.”

In 1975, he went to see a friend who was the headmaster at a suburban prep school to inquire about a teaching job. Later that same week, he was working on a profile of the singer Bobby “Blue” Bland, waiting to watch Bland’s horn section rehearse at Boston’s Sugar Shack nightclub, “this alluring den of iniquity,” as he calls it.

“It was just after Christmas, and all the tinsel is still up but all the glamor is gone, and there’s nobody left in the place except people transacting the kind of business that people transact, and I’m waiting till 2:30 in the morning, and then Mel Jackson, who’s the head of Bobby’s band, says, ‘Aw, the hell with this, we’re not going to have a rehearsal,’” Guralnick says. “I realized in that moment—and this sounds stupid—but I realized I would rather spend the rest of my life waiting for a horn rehearsal that never happens than go out and teach in this polite prep school environment.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.