POV: I Know the Water Is Coming. But I Can’t Bear to Sell My Family’s Cottage

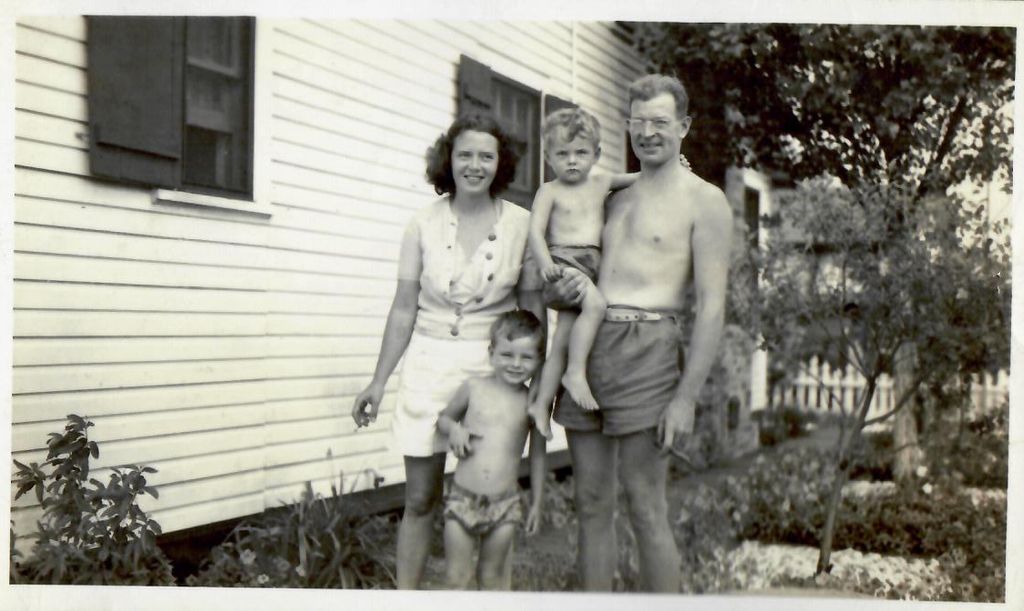

The author’s grandmother, Marie Moran, in Breezy Point, 1947. Photos courtesy of Barbara Moran

POV: I Know the Water Is Coming. But I Can’t Bear to Sell My Family’s Cottage

“I tell myself to sell it, and I’m right. And yet…”

A few days before my father died, he sat up in his hospice bed and pointed to a framed photograph on the dresser. I brought it to him, and he tapped his finger on the glass.

We looked at it together. The photo showed a crowd of 30 outside a house, dressed for summer, leaning together and smiling for the photo. But Dad wasn’t looking at the people. He was looking at a small bungalow, white with red trim, barely visible behind them.

He tapped the glass. “There,” he said. “There.”

“You want to go to Breezy, Dad?”

He nodded yes, leaned back and slept.

Breezy Point is a beach community in Queens, N.Y., a long skinny sandbar poking into the Atlantic, separated from Brooklyn by a narrow bay. It has the nation’s second highest concentration of Irish-Americans, after Quincy, Mass. At least that’s what Wikipedia says, and it rings true to me. My grandfather bought a small bungalow there in 1934 for $750. The house my father longed for from his deathbed.

The place I cannot bring myself to sell.

If you’ve ever heard of Breezy Point, it’s probably for one of two things. It was one of the New York neighborhoods hardest hit by 9/11, partly because so many firefighters live there; 32 of its 5,000 residents died in the attack.

The other thing you might remember was Hurricane Sandy, which walloped Breezy Point in 2012. Floodwater from the bay and the ocean surged over the peninsula, meeting in the middle and filling some homes with more than six feet of water. The storm surge shorted out electrical lines, sparking fires that burned about 150 homes overnight. The water stayed for days. You might have seen a photo of a Virgin Mary statue standing amid the burnt and soaked remains. In the end, 355 homes were wrecked in a community with fewer than 3,000 houses.

People are still rebuilding now.

They are still rebuilding, even though the sea is rising and the next Sandy is only a matter of time. By 2050—when my kids are grown—sea level around Breezy will have risen somewhere between 8 and 30 inches. As the world warms, hurricanes grow in speed and size each year.

Our bungalow got whacked during Sandy, flooded and mostly ruined. My dad built it back without flood protection, not wanting to spend the extra money. Breezy Point itself now has berms and drainage to help mitigate flooding, so maybe it’s ready for climate change. But when I look at our bungalow squatting on the sand, I think it’s no match for the next Sandy.

When my dad died in March, the house became mine. Well, it’s not totally mine—there’s a complicated co-ownership with relatives—but the house will be in my name, and I inherited responsibility for it. Soon, I’ll have to decide what to do with it.

Everyone tells me I should sell it—quickly—and they’re right.

I tell myself to sell it, and I’m right.

I’m an environmental reporter. I believe the science, and I know the water is coming. I also know the debate about “entrench or retreat.” Climate change drives a hard bargain: some communities will be saved, and some will be left to succumb to the sea, or the desert, or wildfires and mudslides. Maybe we’ll all find a way to curb climate change and mitigate the damage, but most likely, Breezy Point is on borrowed time. The smart thing to do is sell now, divvy up the proceeds and buy a place in Maine.

And yet.

When I sit on the bungalow’s porch on summer nights I can hear the bell of the channel buoy, swaying in the bay. The logic of science, the checkbook calculations: they have no power here. As Pascal said, the heart has its reasons, which reason does not know.

This place is the thread that holds me to my father, whom we buried with a seashell in his casket; my grandmother, that smart-mouthed long-legged Garvey girl; my grandfather, son of a Galway man; all that mad tribe of Brooklyn, and my wider, dimly lit tribe across the sea.

I stand on the wet sand and look across the Atlantic, squinting to see them. The water roars and swirls, cold and gray, my sense of loss and longing a thousand fathoms deep. But they are with me, here. All of them.

It feels right to stay, and take my chances with the sea.

Barbara Moran (COM’96) is the senior producing editor for Earthwhile, WBUR’s environmental vertical, and can be reached at bmoran@bu.edu.

This commentary originally appeared in “Cognoscenti,” WBUR’s online opinion page.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.