Where Is COVID Research Going Next?

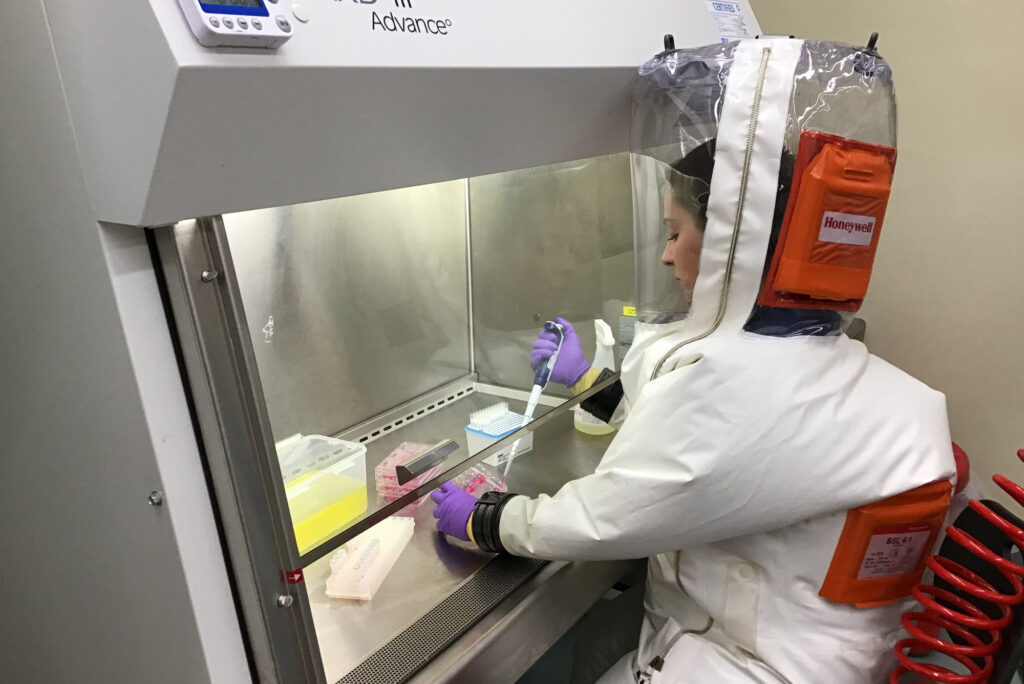

Anna Honko, a researcher at BU’s National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL), conducts an experiment using live SARS-CoV-2 virus inside a high-containment NEIDL lab. Photo by Sierra Downs, courtesy of the Griffiths lab/BU NEIDL

Where Is COVID Research Going Next?

NIAID divisional director Matthew Fenton, BU alum and former professor, talks about vaccine safety and what’s next for COVID research funding and the pandemic

Behind the scenes of the race to develop COVID vaccines in record time, Matthew Fenton and his colleagues at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) worked around the clock to get more than $3 billion in emergency funds from the government funneled into clinical trials as soon as possible. It’s been an unprecedented year for Fenton’s team, and for his boss, Anthony Fauci, the NIAID director.

Since the 1980s, Fenton has been helping us better understand how the human immune system works, and his research has enabled novel therapies and vaccines to treat and prevent infectious diseases. His work has unraveled new insights into how autoimmune disorders and allergic reactions are sparked, and how they can turn into chronic, life-threatening diseases.

At NIAID, where Fenton has been director of the division of extramural activities since 2012, he’s instrumental in routing federal research funds to scientists around the country, overseeing the management of NIAID grants, contracts, peer review, training, and career development, as well as Small Business Innovation Research programs. Previously, he spent 20 years doing biomedical research right here on BU’s Medical Campus. (After earning his PhD in biochemistry from BU School of Medicine in 1984, he did postdoctoral research at Massachusetts Institute of Technology before rejoining BU School of Medicine as a faculty member.)

On March 31, he’s returning to BU once again (this time virtually, of course) to give a talk to researchers about NIAID’s priorities and how they’ve changed because of COVID. He will also talk about the budget for the National Institutes of Health, COVID-related grant policies and flexibilities, NIAID’s response to COVID—including Operation Warp Speed and the COVID-19 vaccine trials—and future coronavirus initiatives that NIAID is planning. Ahead of his talk at BU, The Brink caught up with Fenton to ask about his career and what he’s experienced at NIAID during the pandemic.

Q&A

With Matthew Fenton

The Brink: You and six other directors work with Anthony Fauci to lead the NIAID. What’s it like reporting to and working for Fauci?

Fenton: He’s an extremely high-energy guy, and he’s very passionate about public health. Typically, NIAID’s directors would gather together with Dr. Fauci once a week to discuss our priorities, but since the start of the COVID pandemic, he’s been pulled away to give guidance to the White House and to do the important job of communicating with the public about coronavirus. He believes it’s very important to get the scientific message out there to people, so while he would probably rather be focused on research, he’s spent a lot of time doing talk shows and giving media interviews to continue putting that evidence-based perspective out there—especially important as we’ve seen a lot of misinformation about COVID-19 get shared over the course of the pandemic. Luckily, our team of directors shares Dr. Fauci’s understanding of what NIAID’s priorities are, so we’ve been able to stay on track with our mission despite having a little less of Dr. Fauci’s time over the past year.

At the start of your scientific career, you were a graduate student and eventually a professor and researcher at BU School of Medicine—totaling 20 years spent studying the immune system here at BU. What are one or two of the most memorable breakthrough findings that you were a part of during that time?

I was particularly excited about doing early research on the function of Toll-like receptors within the human immune system. (Toll-like receptors are located on the surface of immune cells; they have the job of scouting the human body for the presence of foreign invaders, like bacteria, viruses, or other microbes that don’t belong.) At the time, they were a relatively new discovery. They act as gatekeepers of the human body, triggering an innate immune response when they detect infection. Today, toll-like receptors continue to play a role in many vaccines, instigating an immune response and training the body’s immune system to recognize certain viruses.

What are some of the biggest disruptions or challenges NIAID has faced due to COVID, and how did your team pivot?

In normal times, NIAID administers almost $5 billion worth of research grants and contracts each year. Because of COVID, NIAID received an additional influx of $3.3 billion in emergency research funds, which we used to fast-track the progress of researchers who were trying to understand the SARS-CoV-2 virus and its impact on the human body. Critically, those funds also allowed us to open up COVID vaccine clinical trial sites and hire enough staff to complete those clinical trials in record time. So, the NIAID team has been working around the clock—12-hour days are the new norm around here—to manage all those funds and make sure research funding can go to work quickly.

What areas of COVID research are of the most importance to NIAID?

A priority area is to understand the long-term effects of COVID infection, which researchers are very much still learning about. We are just getting to the point in the pandemic, over the one-year mark here in the US, where we are reaching enough long-term data for scientists to begin asking these research questions. So, this is an area we will be focused on supporting with research funds.

You evaluated an H1N1 vaccine for safety and efficacy in people with severe asthma. Are there lessons you learned from that experience that might address some of the concerns that people have about side effects—including anaphylaxis—in response to the COVID vaccines?

Something that’s really important to keep in mind, when we think about the COVID vaccines and how safe and effective they are, is that the only reason they were able to be developed so quickly is because of how much money we threw at this effort—billions of dollars that was authorized by the federal government to get a vaccine in the works. It’s not because any scientific shortcuts were taken; the COVID vaccines went through the same clinical trial process to gain FDA approval that all other vaccines must go through. The difference is that, because of the funds allocated toward developing COVID vaccines, we were able to hire a workforce and open multiple clinical trial sites to move the COVID vaccines through that process faster than would normally be possible.

What is your prediction for how this pandemic will end? Will it fizzle out after herd immunity is reached, or will COVID always be among us, mutating and requiring additional, updated vaccinations?

There are many very smart people who have different predictions than me, but my personal opinion is that COVID will not disappear. I think it will be very difficult for the US to reach true herd immunity. We already see some states have opened back up, giving the virus more opportunities to spread between people. The more the virus spreads, the more chances it has to mutate into new variants. Although the FDA-approved COVID vaccines at this time appear to be effective in preventing infection from the new variants, at some point it’s likely that new vaccine formulations will be developed to account for variations in the SARS-CoV-2 virus. As long as the virus keeps spreading and mutating, we’ll likely need booster shots to keep serious illness, hospitalization, and death rates down.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.