A Scientist Ponders Religious Depictions of the Stars

Julius Schiller’s depiction of the Holy Family’s St. Joseph, the ideal husband and father. Courtesy of the Mendillo Collection

A Scientist Ponders Religious Depictions of the Stars

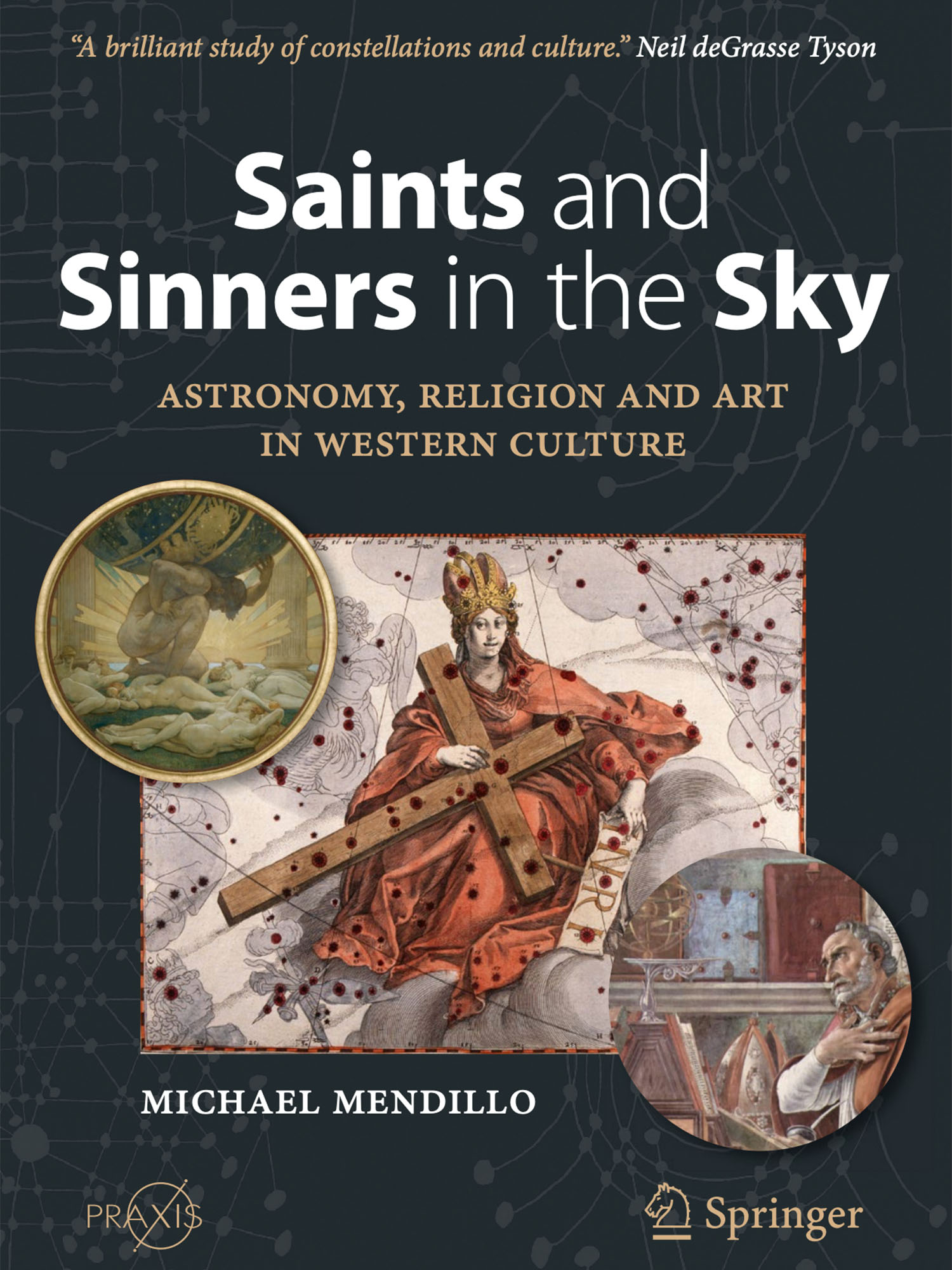

BU astronomer Michael Mendillo’s new book, Saints and Sinners in the Sky, explores the connections between art, religion, and astronomy

When asked about the audience he hopes to reach with his latest book, Michael Mendillo’s answer: “Explorers.”

In Saints and Sinners in the Sky, (Springer-Praxis, 2022), Mendillo (GRS’68,’71), an interdisciplinary studies enthusiast, explores the connections among astronomy, religion, and art. The College of Arts & Sciences professor of astronomy surveys different depictions of the heavens by secular and religious observers over centuries: from ancient cave paintings of constellations to pioneering medieval atlases and sublime paintings, both medieval and modern.

“I like to urge this: when you next go to a museum of art, locally or abroad,” Mendillo tells BU Today, “seek out a medieval, golden-sky painting. Then take it in your memory to the different floors where the Renaissance, Impressionist, and Surrealist images are for connections. It becomes personal.”

We spoke with Mendillo about his new book and what science and religion each bring to describing our galactic neighborhood.

Q&A

With Michael Mendillo

BU Today: As a scientist, what interested you in religious art that depicts the cosmos?

Mendillo: I, and all other observational astronomers, are deeply interested in the visualization of nature. How do you portray celestial features in ways that help us understand their fundamental place in the natural world? Artists address the same issue in their works. In medieval times, nature was often portrayed in “representational” ways. For example, a religious scene, such as the Nativity, with the sky painted gold, in order to show that the domain above Earth is a far better place than the Earth, air, fire, and water we experience. When the famous 14th-century artist Giotto painted the Nativity, he painted the sky blue and used a comet in place of the Star of Bethlehem to guide the three kings. A careful analysis of the celestial events that occurred during the early 1300s reveals that it was Halley’s Comet that appeared during the time Giotto was painting his masterpiece, and he must have been inspired by it.

At the end of Jesus’ life, there was another astronomical event—a solar eclipse—and artistic portrayals of that scene appear in drawings, paintings, mosaics, and tapestries.

The title of the book describes a remarkable initiative to replace the names and images of the 12 signs of the Zodiac—pagan “sinners”—with images of Jesus’ 12 apostles—Christian “saints.” This attempt to “Christianize the heavens” by Julius Schiller, a 17th-century German lawyer and astronomy enthusiast, contains some of the most beautiful portrayals of celestial images within the contexts of religious themes in all of Western culture. First-ever Latin translations of 17th-century texts are used to explain the choices of images, themes, and connections between astronomy, art forms, and religious doctrine.

Moving beyond religious connections, the book explores secular attempts to use artistic media to portray constellations and other celestial scenes. Most famous, of course, is The Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh. I move beyond that iconic example and treat works by John Singer Sargent—his celestial sphere at the Museum of Fine Arts—constellations by Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró, and imaginative works with astronomical objects by Edvard Munch, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Salvador Dali.

BU Today: Could you briefly summarize the key players and points vis-a-vis artistic renderings of the heavens, both secular and religious?

Mendillo: The first examples of artistic renderings of constellations appear in cave paintings dating to 20,000 or more years ago. When the printing press became available, star atlases started to appear, including a beautiful set of prints by Albrecht Dürer. During the “Golden Era” of celestial cartography in 16th- and 17th-century Amsterdam, the most famous and beautiful of all celestial maps are those of Andreas Cellarius. He summarized the earlier approaches of Johann Bayer and then displayed the remarkable attempt of Julius Schiller to change all of Bayer’s classical constellations with biblical figures. This “Christianizing of the Heavens” is one of the major stories told in the book, using first-ever Latin translations of original texts.

BU Today: Most modern readers probably see religious depictions of the heavens as faith intruding in what should be science’s realm. Your book suggests you see value in such depictions?

The anthropologist Steven Jay Gould introduced the concept of science and religion being “non-overlapping magisteria,” a notion opposed by both religious and secular scientists. The concept of “origin of the universe” necessarily brings up creation scenarios that range from Genesis to the Big Bang hypothesis described in all Astronomy 101-102 textbooks and courses. It is good for society to think about origin issues, and Saints and Sinners in the Sky offers many images useful in that dialogue.

BU Today: Is there a lesson or takeaway to be drawn from competing illustrations of space by science and religion?

I had not considered multiple views of the universe in science, and different religious descriptions of nature, as a competition for the best view of our place in the physical universe. Yet we need, of course, multiple pathways of seeing and understanding. The new Webb Space Telescope provides views of new and familiar objects using a portion of the spectrum of light—infrared, i.e., heat—that we do not “see” in the traditional use of that word. The resulting images are portrayed using colors assigned to the amount of heat they emit. We also now have an image of a black hole, something we do not see with our biological eyes.

BU Today: I wonder if readers will be surprised that many pioneering astronomers and other scientists were people of faith?

Fortunately, when a paper is submitted to a scientific journal, the editor does not ask the authors to divulge their religious affiliations, or lack of them. We know that Galileo and Newton were scientists of faith, as were and are many others today. Atheists are also well represented in the inventory of scientific disciplines. I did not address this issue in the book. I had no hidden agenda and hope that author neutrality comes across.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.