This Halloween, the Scariest Monster May be Technology, Subject of a New Horror Anthology by BU’s Aaron Worth

New horror anthology by CGS’ Aaron Worth shows how evolving technology has long spooked writers and readers

Thought TV was bad for you? You don’t know the half of it, as Aaron Worth’s new horror anthology collects spooky tales about technology. Photo by francescoch/iStock

Halloween’s Scariest Monster Could Be Technology

New horror anthology by CGS’ Aaron Worth shows how evolving technology has long spooked writers and readers

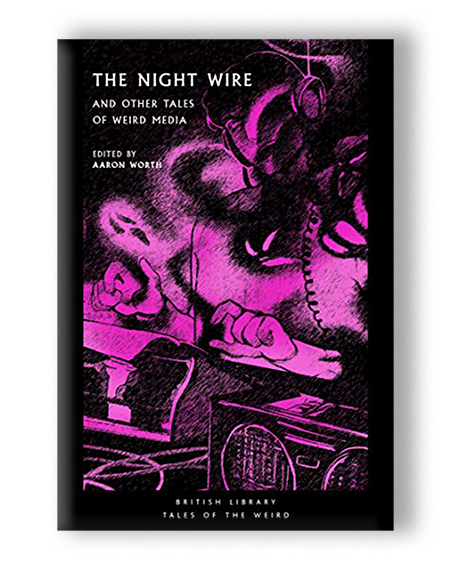

“The entire category of Gothic, horror, the weird—whatever you want to call it—is the offspring of new, nonliterary media technologies,” writes Aaron Worth to introduce his new anthology, The Night Wire: and Other Tales of Weird Media (British Library).

To make his point, Worth, a College of General Studies associate professor of rhetoric, has assembled 17 horror stories that were originally published between 1890 and 1955. The collection demonstrates tech’s enduring role in literary nightmares.

That relationship began, the introduction says, with the first Gothic novel, 1764’s The Castle of Otranto, influenced by the magic lantern, an early projection device. More recent examples include 2002’s The Ring, a film tapping tech terror by depicting the unfortunate consequences to viewers of an apparently cursed videotape.

Worth’s collection itself features well-known (Rudyard Kipling, H. P. Lovecraft) and less renowned authors and stories about various technologies, from a device that reveals past events inside a room to a telephone with really long-distance service (you’ll have to read the book).

Worth, who edited last year’s spooky collection Randall’s Round, discusses his latest below.

Q&A

with Aaron Worth

BU Today: What is it about tech that sets off nightmares?

Worth: It’s something of a critical cliché to view the Gothic novel—the 18th-century grandparent of modern horror fiction and film—as a product of the Enlightenment. It’s an “irrational” reaction to a dominant ideology [that was] valorizing rational thought, scientific progress, and so on. Technology is obviously part of that Enlightenment package, so it makes sense that the Gothic, and later horror and the weird, would be interested in probing the darker side of tech.

Then there’s the fact that media technologies in particular are unusually intimate ones—we use them to express ourselves, they are extensions of our senses, as Marshall McLuhan said. They bring us into close contact with other people, and so on. There’s plenty of nightmare fuel there. Finally, it’s important to recognize how much literature has itself been influenced and transformed by new media technologies in the modern period, from the magic lantern shows of the 18th century to the digital media of our own time. I think that influence has a lot to do with the unsettling sense of anxiety which media techs often bring to the narrative forms which they’ve invaded, so to speak.

BU Today: Has the nature of those nightmares changed as technology has changed and advanced? Or do the same things frighten us today that frightened readers of Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto?

Worth: There are definite continuities. Take the idea, for instance, of a weakened boundary between representation and reality, embodied in the trope of the ghost or monster escaping from the media world into the “real” world of the story. You see this in Walpole’s seminal novel just as you see it in The Ring films from the 1990s to the present. By implication, one finds oneself wondering, what’s to stop the monster from taking the further step of entering the real real world?

Technologies of communication in particular have always lent themselves to uncanny scenarios involving contact with dead, demonic, or otherwise monstrous entities—the telegram or phone call from the other side of the grave, for instance. On the other hand, particular technologies do have their own special characteristics, giving rise to novel flavors of terror. Look, for example, at the explosion in recent years of horror films centering on social media networks of various kinds, haunted apps that predict your death, bring some evil entity ever closer to you, and so on. While they ring changes on earlier tropes, these are clearly products of our own technologically saturated, massively networked age.

Technologies of communication in particular have always lent themselves to uncanny scenarios involving contact with dead, demonic, or otherwise monstrous entities.

BU Today: What was your aha moment, when you realized the tech/horror fiction nexus?

I’m not sure I can pin one down. I’ve been interested in both the history of technology—especially media technology, and especially archaic media technologies—and horror fiction for a long time on their own terms. At some point, I suppose the two streams simply ran together. I do remember being quite unsettled by Gore Verbinski’s 2002 version of The Ring. Sometime after that, I noticed that I had begun keeping a mental list of stories by classic writers such as M. R. James and H. P. Lovecraft featuring uncanny daguerreotypes, phonographs, and the like. When the British Library began publishing its excellent Tales of the Weird series, I thought it would be a fabulous place to try pitching a collection of such tales.

BU Today: Do you happen to know how well-versed in science and tech the writers you’ve collected were? Might a techie object that they—and we—were and are scared of tech because we don’t understand it?

Throughout history, whenever a new technology appears, you tend to see both positive and negative, optimistic and pessimistic, responses at the same time. For instance, in Plato’s myth about the origin of writing—arguably the first media technology—you have the inventor saying, “This is awesome! It’s going to make geniuses of us all!” The skeptical king Thamus, on the other hand, says, “This is going to make us stupider, because we won’t exercise our memory any more!”

You see the same thing in stories about new media: some writers dwell on their horrific potential, while others use them to fantasize about utopian scenarios. Clifford in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s quasi-Gothic House of the Seven Gables is a good example of the latter. That said, it’s probably more a matter of authorial intention or temperament than of technological literacy—H. F. Arnold’s 1926 novel The Night Wire, for instance, is almost certainly based on its author’s own experience, either as an operator or someone working closely with operators in the news business. Rudyard Kipling was a writer fascinated with, and knowledgeable about, new media, who exploited them to evoke feelings of both terror and wonder. An example of the latter is “Wireless,” included in the collection, a story he wrote after playing host to radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi at his home.

BU Today: Does using The Night Wire as your anthology’s title indicate that that’s your favorite story of the bunch?

It’s more that The Night Wire struck me as nicely advertising the contents of the collection as a whole, in that it conveys the idea of “media” wedded to that of “darkness.” But in fact, that story is an old favorite of mine. I remember first encountering it years ago in some horror anthology or other, and it’s stayed with me ever since. I relish its creation of atmosphere—the almost-deserted news office in the small hours of the night, linked by wire with the fog-shrouded city of Xebico. As well as its grim final image of—but I won’t spoil it.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.