BU’s Sexual Assault Response & Prevention Center: 10 Years of Helping and Advocating for Students

SARP staffers past and present look back at a decade of supporting students through trauma

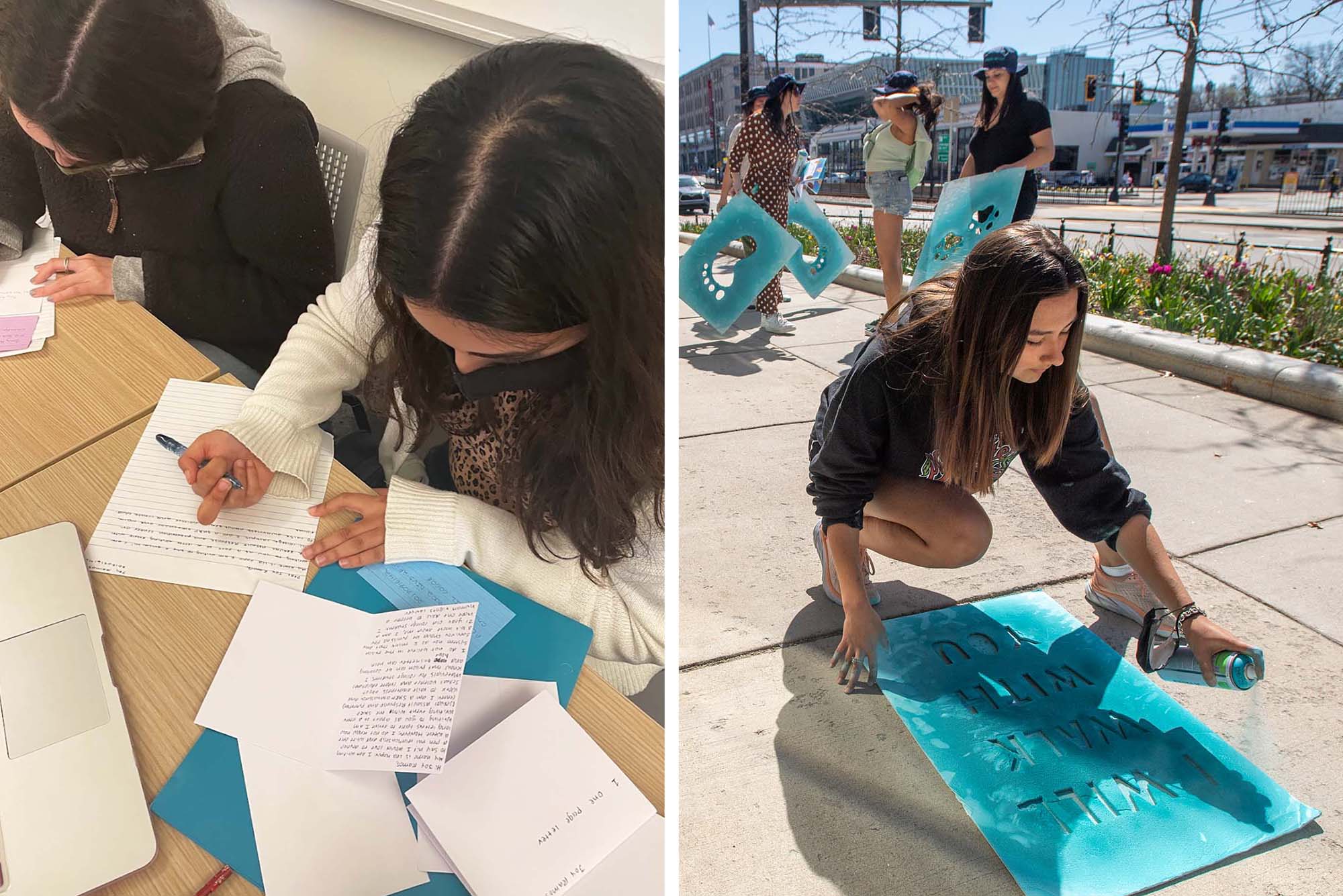

SARP’s prevention- and connection-focused events include things like the Incarcerated Survivors Letters Writing Initiative (left), started by a former SARP student ambassador, and “I Will Walk with You” (right), an annual public art project during Sexual Assault Awareness Month in April. Left photo courtesy of SARP; right photo by Cydney Scott

BU’s Sexual Assault Response & Prevention Center: 10 Years of Helping and Advocating for Students

SARP staffers past and present look back at a decade of supporting students through trauma

Trigger warning: This article discusses sexual assault.

Just over 10 years ago, the idea of a campus center solely dedicated to helping survivors of sexual assault seemed like a leap.

Although 2012 came a year after the Obama-era “Dear Colleague” letter instructing colleges and universities to lower their burden of proof in campus sexual assault cases, among other Title IX–related guidelines, the global MeToo movement was still five years away. Sexual assault on college campuses was a subject fraught with high-profile scandals and murky reporting processes, leaving both survivors and the accused with little recourse or direction.

Students at Boston University wanted better.

A group of them involved with the Center for Gender, Sexuality, & Activism (CGSA) came together in 2012 to propose an on-campus department dedicated to preventing sexual violence and assisting survivors, among other campus culture reforms. The students’ proposal for a center—and accompanying petition—echoed the suggestions of a faculty and staff task force convened by President Robert A. Brown after sexual assault charges were brought against two men’s hockey team players in 2011 and 2012.

The message was clear, and received: in fall 2012, Brown established the Sexual Assault Response & Prevention Center (SARP) as a new department within Student Health Services under the direction of longtime BU crisis counselor Maureen Mahoney.

A decade later—and half a century after the passing of Title IX—SARP is marking 10 years of helping victims of sexual assault, domestic violence, and interpersonal violence reclaim agency over their lives. The center has assisted approximately 2,500 survivors since its inception, translating to more than 17,000 individual counseling and advocacy sessions and over 780 hours of group counseling.

It’s now among scores of sexual assault crisis centers on college campuses—something that would have been almost unthinkable 10 years ago, says SARP director Nathan Brewer, who took over when Mahoney retired in 2020.

“I think the biggest takeaway is that the expectation has gone from, ‘Oh, this is a really cool and unique service’ to ‘If a school doesn’t have a crisis center, why are they not providing that service? This is absolutely something that all schools would benefit from,’” Brewer says.

An expanding center: support, training, advocacy

SARP’s offerings have greatly expanded since its founding. In addition to providing free and confidential counseling and advocacy services to survivors of sexual violence, the center has significantly ramped up its prevention arm to include a range of student support services, such as comprehensive bystander intervention training—mandatory for leaders of clubs receiving Student Activities Office funding as well as varsity athletes—webinars, workshops, prevention-focused events like the popular Cones for Consent, and an increased presence at new student Orientation, among other offerings. To date, more than 15,000 students have attended SARP training sessions. The center also recently began a pilot program in collaboration with the University’s Office of the Ombuds to provide support and education to students groups where members have harmed other members.

On the clinical side, SARP’s personnel count has more than doubled since its founding. The center—where regular staff includes 3 full-time and 2 part-time counselors, 4 interns, 2 preventionists, 16 student ambassadors, and an administrative coordinator—serves survivors of trauma in general, not just victims of sexual or domestic violence. (While that was technically always the case, Brewer says, the offerings have become more substantial in recent years.) That means SARP counts efforts like Overcoming Family Challenges, a new support group for students experiencing familial estrangement, among its group therapy offerings.

In recent years, all SARP clinicians have received training in cognitive processing therapy, a type of behavioral therapy specifically geared toward patients who’ve experienced trauma. This semester, SARP also was given oversight of the “Survivor Fund,” a donor-generated fund that allows the center to reimburse students for expenses such as STI testing, new apartment locks, emergency hotel stays, and replacement clothing.

Sarah Merriman (CAS’12), one of the CGSA students who wrote the initial proposal for SARP, has followed the center’s work since her graduation in 2012. She says it’s more than lived up to the vision she and her peers envisioned. Sexual violence on college campuses is “an incredibly hard issue to tackle,” Merriman says. To stop assaults and change campus cultures, “you need passionate and dedicated experts who can integrate themselves at the school; you need both crisis intervention and prevention. SARP is doing that, and it’s now one of the best-resourced centers of its kind in the country. I don’t think anyone could have predicted how much it has been able to grow.”

Awareness: a post-MeToo world

The center’s expansion is also a testament to society’s increased awareness of sexual violence and the importance of consent. SARP founding director Mahoney says that when she first started as a crisis counselor at BU in the early 1990s, the cultural landscape was vastly different. Conversations around sexual harassment had entered the mainstream, in part because of the testimony of Anita Hill during the 1991 confirmation hearings of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas and 1994’s Violence Against Women Act, but nuanced discussions of power dynamics were still a ways away.

The knowledge bar is so much higher for students who’ve come of age following the MeToo movement, notes Mahoney, who continues to work at SARP as a part-time crisis counselor. Now, “students come to college already with an understanding of consent,” she says, and far lower thresholds for inappropriate behavior. (She points to a recent Boston Globe story about Rhode Island middle schoolers who logged and reported a teacher’s misconduct, leading to an investigation.)

That’s not to say sexual violence has disappeared, of course. Nor has the justice system become a reliable mechanism for prosecuting perpetrators of that violence. Rather, greater cultural knowledge has allowed a growing number of survivors to take control of their narratives and push back against stigmas surrounding sexual assault.

That’s something Ashley Slay (SSW’16), SARP associate director of interpersonal violence prevention, says she’s grateful to be a part of. “The MeToo movement opened up doors for survivors to speak their truth and harm-doers to be held accountable for the hurt they’ve caused. Knowledge and engagement with topics related to consent, respecting boundaries, and resources for survivors seem to be everywhere,” says Slay, a former youth outreach coordinator for the Boston Area Rape Crisis Center.

“Violence on campus hasn’t stopped, but what I have noticed is more students becoming impassioned about preventing violence, people feeling empowered about their ability to make a difference, and survivors finding themselves at SARP to get the support they needed.”

Supporting students—whatever they decide to do

SARP has a variety of resources for students who come for help. Offerings include a 24/7 crisis line, individual and group counseling, advocacy services, safety planning, support groups, emergency reimbursement, and referrals to external legal and medical providers. Consistent with the other clinical departments in Student Health Services, all are confidential and free of charge.

Being able to meet students where they are in the healing process is something both Brewer and Mahoney are proud of. For one, effective crisis counseling doesn’t necessarily mean encouraging a student to report an assault or file a Title IX complaint, they point out. (Sexual assault cases are notoriously difficult to prosecute and can end up retraumatizing or endangering survivors in the process.) Instead, the goal is to “support students in whatever they decide to do—or not to do” in a nonjudgmental environment, Mahoney says. When a student comes to SARP for help, the goal is to help them figure out what their options are, explain the foreseeable consequences of choices they make or don’t make, and then support those choices using resources available at BU and beyond.

For example: should a student need emergency housing following a violent incident, Brewer says, “I can call up the person I know in BU Housing and say, ‘I need to house this person within 24 hours,’ or I can contact BU Dining and say, ‘We need to get this person meal swipes because they don’t have money to eat after everything.’” The same goes for contacting academic advisors and professors should a student need to take a leave of absence. (SARP counselors can also connect students with services outside of BU.)

That’s the benefit of being embedded within the University, Brewer adds. “On the whole, people respect what SARP does and respect that when a SARP clinician is calling or asking for something, it has a weight to it that is meaningful.” Much of the credit belongs to Mahoney and her staffers, he says, for working to build relationships in the center’s early years. But it also belongs to the BU community for recognizing the value of what SARP provides: “Our partners understand that [providing accommodations] could be the difference between someone withdrawing from the University or not and ending their academic career.”

Looking to what survivors want and need

Looking back over the past 10 years, SARP staffers say the progress the University has made has been impressive and heartening. Thousands of BU students receive training each year on topics such as bystander intervention, sex positivity, consent, and forming and maintaining healthy relationships. SARP’s newest prevention training, a series of four workshops for graduate students aimed at stopping gender-based harassment in academic settings, has been presented nationally as a model for other centers and programs. That’s a long way from the single 90-minute bystander training session the center originally offered, Brewer says.

However, he acknowledges that there will always be more work to do. (One big SARP priority: establishing a physical presence on the Medical Campus.) While sexual violence is not unique to college campuses, it remains uniquely prevalent in university settings. Sexual assault crisis counseling is also a relatively young field in comparison to other psychiatric specialties, he points out, so there’s always more to learn in terms of best practices for serving survivors.

Both he and Mahoney are grateful for students who continually push BU to be better. “The students are always advocating for us to be more social justice–focused and more intersectional in our approaches. In turn, we really push to hear those voices and to make space for what survivors want and need, and what the community wants and needs,” Brewer says. “I’m so glad that these younger generations are finding that voice and being vocal, like: ‘This is what we need to see on campus.’”

And historically, even when other aspects of a sexual assault case may not turn out how a student had hoped, Mahoney notes, students usually say that SARP was helpful for them. That’s just part of what keeps her, Brewer, and their colleagues showing up for work every day. The individual reasons are legion, but most of them boil down to a common theme: helping students reclaim the direction of their lives to find the other side of trauma.

It’s a privilege, Brewer says: “You know, I think most of us take the perspective of being honored that we get to do the work.”

The Sexual Assault Response and Prevention Center is at 930 Commonwealth Avenue. You can book an appointment through the Student Health Services portal, PatientConnect, or call SARP directly at 617-353-7277. If you’ve experienced a sexual assault within the past five days, call the clinic so a crisis counselor can provide you with more urgent care. SARP’s 24/7 crisis hotline can also be reached at 617-353-7277.

Like all departments within Student Health Services, SARP’s services are free and confidential. Note: coming to SARP does not constitute an official report and therefore will not trigger a University complaint.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.