Ibram X. Kendi Wants Children, and Teachers, to Challenge How History Is Taught

He suggests five questions that may help change what they are learning about history

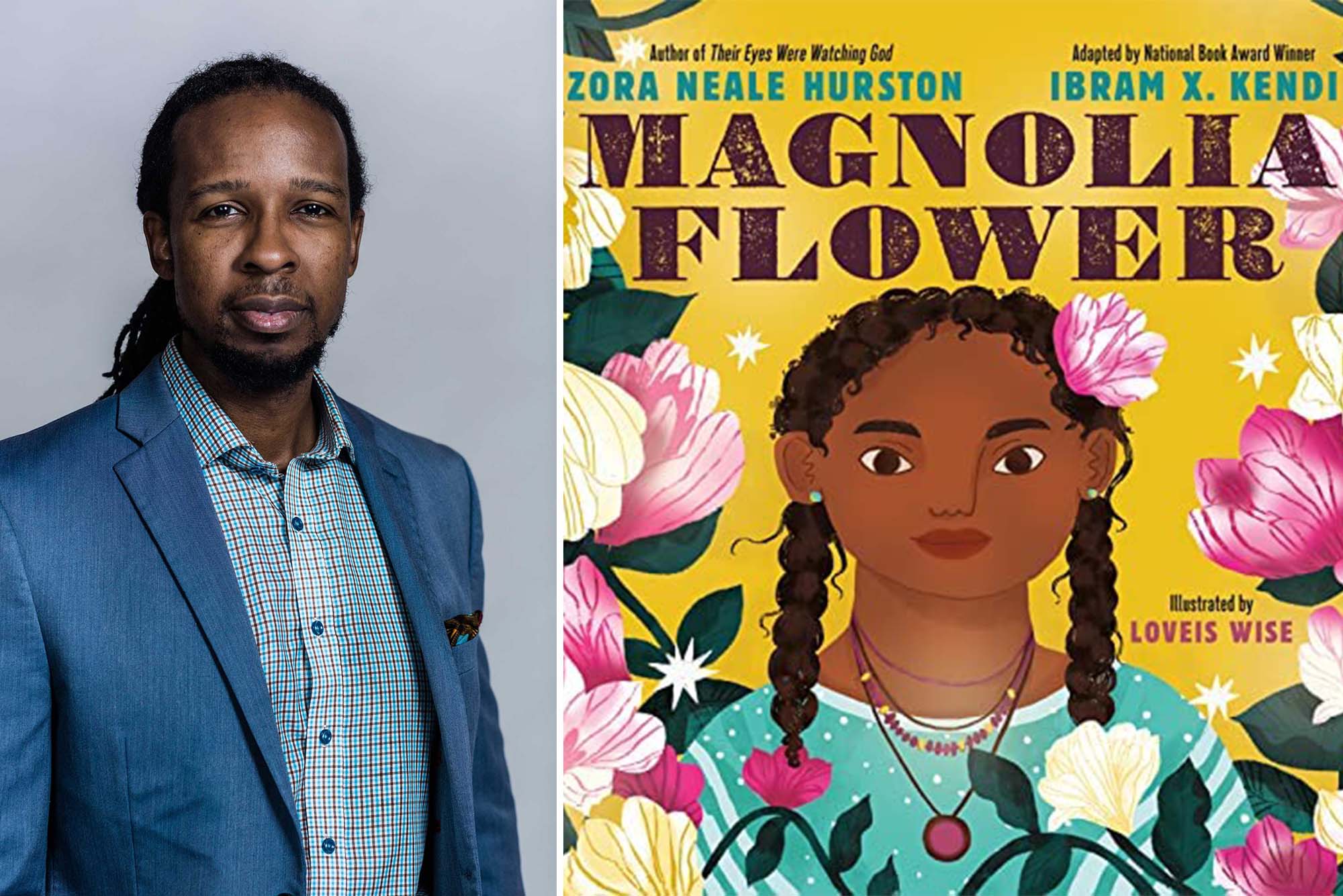

Ibram X. Kendi (left); photo by Janice Checchio. Courtesy of Amistad Books for Young Readers (right).

Ibram X. Kendi Wants Children, and Teachers, to Challenge How History Is Taught

He suggests five questions that may help change what they are learning about history

Ibram X. Kendi wants children to question and challenge the history they are being taught in school or told by their elders. And more important, the founding director of the BU Center for Antiracist Research wants educators to incorporate more difficult questions about history into their lessons, rather than simply continuing to teach history as it’s been taught for generations. Why? Because some of those lessons are inaccurate portrayals of what really happened or why an event happened.

Kendi talked about this in a recent podcast with the Washington Post. In one exchange, podcast host and Post associate editor Jonathan Capehart pressed him on the questions he wishes more children would ask.

Kendi, a National Book Award winner and a MacArthur Fellow, replied: “Like, what was slavery? Like, how did Black people and other people find joy and love during slavery? What was the Trail of Tears? Why were Native people driven from their land? Why is it that after the Civil War, in many ways, Black people felt that they were driven back towards freedom? Those are the questions that I hope kids would ask, kids will ask, and I’m already trying to prepare answers [for] because I suspect they’re coming from my daughter.”

In another recent conversation, at a Los Angeles Times event, Kendi talked about how parents can be more constructive in helping their children understand racism. If a child makes a racially insensitive remark, he said, the appropriate response is not “Don’t say that.”

“The child might stop saying it, but they’re still going to think it,” he said, or possibly repeat it to a friend. But by questioning them about the words, it opens up a dialogue around the differences and similarities people have. “Racism sours and poisons what makes us, what makes humanity beautiful—our differences,” he said at the event.

In his latest published book, Kendi, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of history and the University’s Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities, has partnered with the late beloved African American folklorist Zora Neale Hurston. Magnolia Flower (Amistad Books for Young Readers, 2022), a beautifully illustrated children’s book, is the story of a young Afro-Indigenous girl born to parents who fled slavery and is in search of her own freedom.

With all of this in mind, BU Today reached out to Kendi with a simple request: What questions would you like more educators to incorporate into their lessons to help students see history through a different lens than in the past?

He responded with five provocative questions:

1. How did earlier generations of students learn about US history, and how did what they learn differ with what we learn today? How was it similar?

2. What ideas were typically considered “radical” in the past, but are now considered common sense? In a similar vein, which ideas have fallen out of favor as “common sense” and are now, on the whole, considered ridiculous?

3. Our conception of history as a discipline is formed mostly by our access to written sources. But, historically, written languages are not a constant in human societies. How does this affect not only the people from history we study, but also the very idea of history itself?

4. How have ideas of what it takes to make America “great” changed over time?

5. How important do you think it is for students of history to learn about specific dates and names of “leaders” to garner a good understanding of the past?

In the Comment section below, add your own question about what you think needs to be taught differently from the way it’s been done in the past.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.