This BU Class Aims to Undo a History of Racism in Science and Healthcare

Institutional Racism in Health and Science was created by an interdisciplinary consortium of faculty from CAS and Wheelock

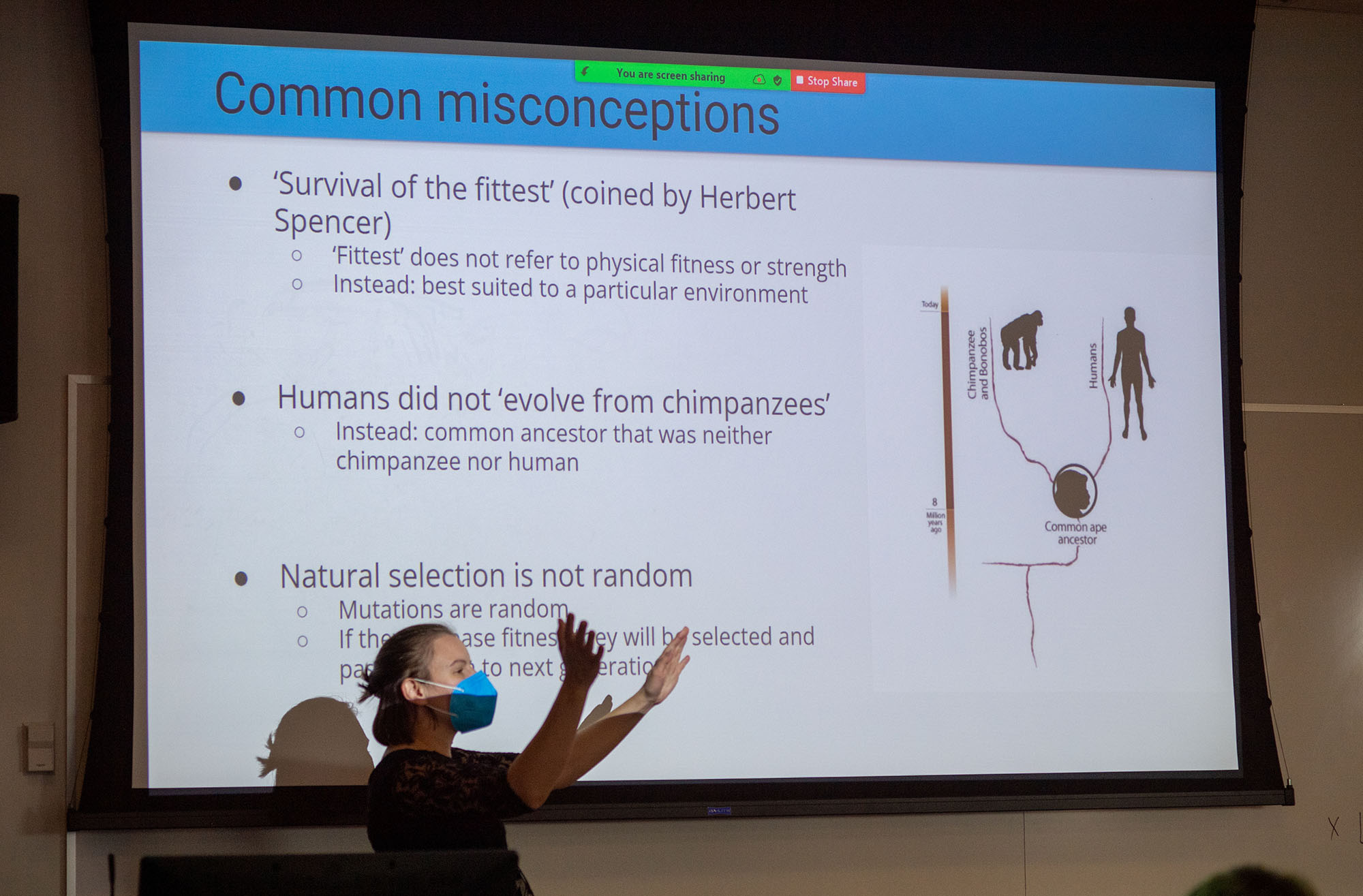

Biology research scientist Melisa Osborne is the main instructor of Institutional Racism in Healthcare and Science, a College of Arts and Sciences course she cocreated with five other Boston University faculty and staff members.

This BU Class Aims to Undo a History of Racism in Science and Healthcare

Institutional Racism in Health and Science was created by an interdisciplinary consortium of faculty and staff from CAS and Wheelock

There are countless ways the medical and scientific fields have perpetuated racism over the centuries. From white skin being the default in many medical texts to infamous events such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, discrimination has been baked into the hard sciences almost since their conception.

If an interdisciplinary consortium of Boston University faculty and staff members has any say about it, the next generation of scientists and educators will be the ones to end that discrimination.

That’s the ethos behind Institutional Racism in Health and Science (IRHS), a fall and spring semester College of Arts & Sciences course open to both undergraduate and graduate students. It was created by a group of six faculty and staff: Melisa Osborne, a CAS research assistant professor; Adam Labadorf (ENG’16), a Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine assistant professor of medicine; Barkha Shah (CAS’12), a CAS biology laboratory supervisor; T. J. McKenna, a Wheelock College of Education & Human Development lecturer; Felicity Crawford, a Wheelock clinical associate professor of special education; and former CAS postdoctoral fellow Theresa Rueger. Osborne is the primary instructor, and Crawford, Labadorf, and McKenna all teach units on their areas of expertise: Labadorf covers genetics and medical data, McKenna science education, and Crawford multi-system solutions to inequality.

The class is open to a variety of STEM and education majors. Most are biology students, with a split among bioinformatics, premed, and research. The Wheelock students taking the course are pursuing a master’s in education for equity and social justice. According to the syllabus, the point of the course is to “develop student competencies in discriminating between fact-based conclusions and unsupported pseudoscience and constructing empirical knowledge for themselves.”

That translates to units on types of cognitive biases, genetic classifications, the human genome, epigenetics, scientific algorithms and data collection, and medical inequalities, among others. Students learn and apply analytical frameworks to each unit, unpacking topics such as increased maternal mortality rates for Black women in America, how to make science education more equitable, and mitigating data biases through class discussions and written assignments.

It’s critical for the next generation of scientists and educators to understand the ripple effects of racism, Crawford says. That’s why the course covers how generational effects of repeated trauma and discrimination lead to poorer health outcomes for communities of color.

“Racism has physiological consequences that can be deadly,” Crawford says. By the end of the course, students are versed in the epigenetic mechanisms by which trauma and “toxic stress” lead to “neurochemical, hormonal, and neurotransmitter alterations, which precipitate chronic inflammatory diseases like diabetes, hypertension, and asthma. These diseases manifest more often in Blacks, indigenous groups, and other peoples of color, with disproportionately deadly consequences.”

While it’s not quite a “scare them straight” model, the course is designed to unpack the legacy of discrimination in the sciences before presenting ways forward, Osborne says.

“We have this philosophy in the class that in order to make science and education more inclusive, you first have to acknowledge the history of it,” she says. “Once you’ve acknowledged that foundation and you can see the inequalities around you, that’s when you can really start thinking about how a more inclusive and anti-racist environment can be built in science, in medicine, in education, in whatever area you’re going into.”

The course grew out of the Black Lives Matter protests that rocked the country in summer 2020. The six BU colleagues, who came together through introductions from their peers, were all troubled by the systemic racism that the killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd laid bare. Each found themselves wondering: How do I undo inequity in my sphere of influence? Eventually, their discussions formed the syllabus for IRHS.

As an educator who teaches future educators, McKenna has a particular interest in courses that take “an interdisciplinary approach to understanding complex social issues.” IRHS, and the faculty behind it, represent academia at its best, he says.

“I feel strongly that the IRHS team that self-assembled to work on this course is an especially exciting example of what can happen in education. When people come together—especially across colleges—around a shared vision, it is incredible what can be accomplished.”

This fall marked the third iteration of the class. As the main instructor, Osborne says she’s consistently amazed by how current events prove the course’s relevance. For example: inequalities in abortion access, debates over sick leave policies amid a “tripledemic” of flu, COVID, and RSV, soaring rates of anxiety and depression in young adults coupled with poor mental health funding—“in the world we live in now,” she says, “I always have fodder that reiterates why this class is needed.”

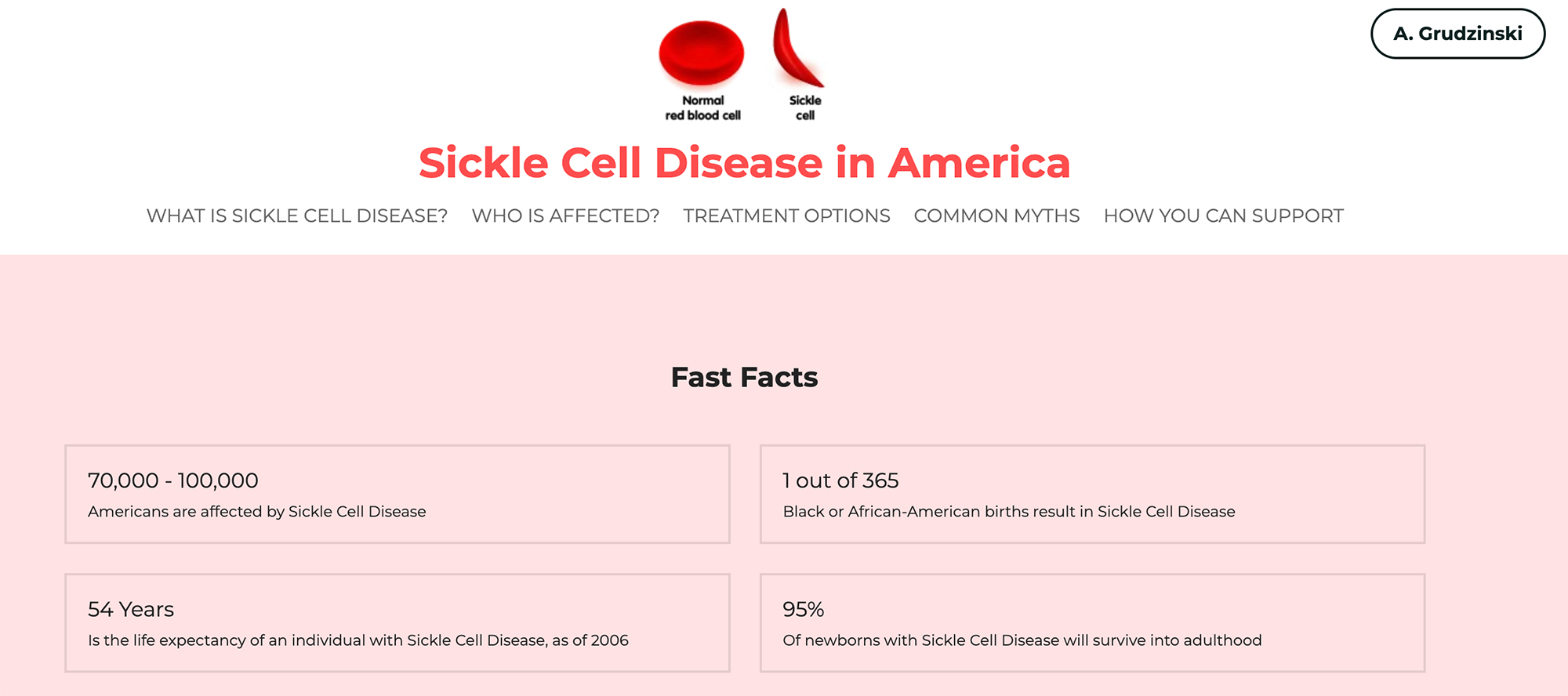

That’s not lost on students. Alexandra Grudzinski (CAS’23), who is studying cellular, molecular, and genetic biology and minoring in public health, signed up for the course because it bridged concepts from her major and her minor. “As someone hoping to pursue a career in the medical field, I believe it’s necessary that I educate myself on the very important topic of racism in the healthcare system,” she says.

Outside of class, Grudzinski volunteers at Tufts Medical Center, where she encounters a wide variety of patients. Her final project for IRHS—which has students create a piece of media or a position paper on a topic of their choice, aimed at an audience of their choice—is a website on sickle cell disease (SCD), a genetic blood disorder that disproportionately impacts African Americans and is under-resourced compared to other disorders.

The project was inspired by a patient she met at Tufts who spoke about the difficulties of finding SCD care in Boston. To help, Grudzinski decided to create a website aimed at SCD patients and researchers that includes resources for patients seeking treatment in the Boston area.

That’s precisely the kind of takeaway the course’s creators want to see.

“The tools of science are neither just nor unjust, and these tools alone won’t provide any solutions. As scientists, awareness of the harms that have been done and can be done will enable us to use our tools more responsibly,” Labadorf says. “My hope is that our students will incorporate consciousness of the legacy of racism and bias in science and medicine to make our society and institutions more just, fair, and inclusive wherever they go.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.