In His New Memoir, Jersey Breaks, Robert Pinsky Traces His Journey to Becoming a Poet

“I had the good luck to be raised among expert joke-tellers, complainers, arguers, schmoozers, boasters, and liars,” Robert Pinsky says in his new memoir, Jersey Breaks. Photo by Gabriela Hasbun

In His New Memoir, Jersey Breaks, Robert Pinsky Traces His Journey to Becoming a Poet

“I work to produce not marks on paper but something more like a song or a monologue, or both,” he writes

It is hard to imagine anyone who has done more to champion poetry than Robert Pinsky. The author of 10 collections of poems—including the Pulitzer Prize–nominated The Figured Wheel: New and Collected Poems, 1966-1996—Pinsky has edited anthologies, written more than a half-dozen prose books about poetry, and translated Dante’s Inferno and the poems of Czesław Miłosz. As director of BU’s Creative Writing Program, he has helped launch the careers of many of the country’s most accomplished young contemporary poets.

But Pinsky, a William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor and College of Arts & Sciences professor of English and of creative writing, exerted perhaps the greatest influence as US poet laureate. During his three terms (1997-2000), he launched the Favorite Poem Project, which invited Americans of all ages and walks of life to share the poems that matter most to them. More than 18,000 answered the initial open call for submissions, resulting in dozens of videos of people reading beloved poems. Those films are available for viewing in a recently completed digital database, housed at Boston University. Pinsky became a de facto ambassador for poetry, appearing on shows as varied as The PBS NewsHour, The Stephen Colbert Show, and The Simpsons.

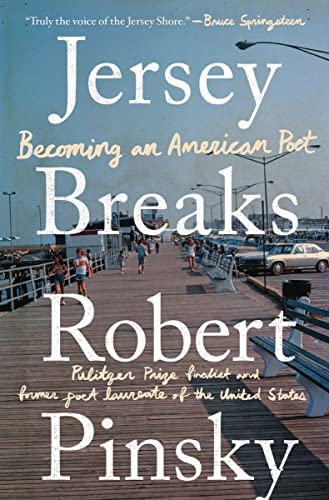

In his new memoir, Jersey Breaks (W. W. Norton, 2022), Pinsky traces his unlikely journey, from a struggling elementary and high school student to an award-winning poet.

Jersey Breaks is also an ode to Long Branch, the down-on-its-heels Jersey Shore resort town where Pinsky grew up in the 1940s and ’50s, and to the relatives, friends, teachers, and mentors who helped him become a poet whose work is distinguished by its musicality.

“I work to produce not marks on paper, but something more like a song, or a monologue, or both,” he writes early in Jersey Breaks. “Even now, as all my life, my poems don’t usually begin on paper, or on a screen. It’s a matter of humming and muttering, grunts and echoes in the vowels and consonants of speech, the melody of every sentence.”

In the book, he pays loving tribute to his family, including his paternal grandfather, a bootlegger during the Depression who served time in jail. Zaydee Pop, as Pinsky called him, would spirit the young Robert into Manhattan in his Packard to keep him company on business trips that were always topped off with a pair of new lace-up shoes and lunch at Jack Dempsey’s Restaurant, where the boy once got to shake hands with the famous heavyweight champion.

He describes how his love of language and his tendency to “think with my ears and voice, putting music above meaning” began early, on train rides to visit relatives scattered across the state. “Little Silver, Hazlet, Perth Amboy, Rahway, and Secaucus were stops on the New York and Long Branch Railroad…the consonants and vowels of their names, chanted by old-school conductors on the way to Penn Station, made a familiar, seductive music,” he recalls.

BU Today recently spoke with the poet, author, and teacher about his memoir and his influences. Pinsky will read from Jersey Breaks and sign copies Thursday, November 17, at Grolier Poetry Bookshop in Harvard Square.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

With Robert Pinsky

BU Today: What made you decide to write a memoir now, at 82?

Pinsky: The 2022 fragmentation in the news, the current bigotries and enmities and nationalisms and nativism set me thinking about the differences and similarities in the time and place of my origin.

BU Today: What were the biggest challenges you encountered in writing the book?

Pinsky: I had to write about ethnicities, races, religions in a way that was candid, clear-eyed, and unstereotyped. That required connecting the neighborhood and town of my youth with my project as poet laureate and the videos at www.favoritepoem.org.

BU Today: This isn’t a traditional autobiographical narrative. Can you talk about what you set out to do?

Pinsky: Thank you for saying that—I did want to do something beyond pure memoir: to express my mixed feelings—patriotic and doubtful, loving and loathing—about my country, my town, my family. While telling good stories and jokes too.

BU Today: What surprised you the most in writing the book?

Pinsky: The unexpected difficulty—the many drafts. “Repeated improvising,” in a way.

BU Today: In the book’s prologue, you state that your journey to becoming a poet can be traced to growing up in Long Branch. How did the town shape you, as a person and a writer?

Pinsky: In a historic resort town—painted by Winslow Homer, the beach place where Ulysses S. Grant, James Garfield, and Abraham Lincoln went, as did many famous gamblers and criminals—the past is present. And I grew up among skillful working-class joke-tellers, complainers, and arguers.

BU Today: You write about your parents’ financial struggles, their sometimes complicated marriage, and the catastrophic brain injury your mother suffered at 34 and the mental health struggles that followed. Was it hard to revisit some of those moments?

No, it was not hard—these are familiar moments that I have visited more or less every day of my life, the material of my storytelling, my dreams, my writing. In a way, the work was to feel it again, in some new way.

BU Today: What do you think your parents would have made of Jersey Breaks?

I hope they would laugh at some of the wise-guy lines. I know they would correct some of the facts. They would hope it sells enough to make money.

BU Today: You write that as a young teenager, music saved your life. How?

Playing the saxophone was the only thing I did well. It gave me an identity, you could say.

BU Today: You describe yourself in the book as frequently feeling like an outsider. Do you still feel that way today?

Most alert Americans—even Harvardy people with Mayflower names—feel a bit like an outsider. The country is that manifold, in great and not-so-great ways.

BU Today: One of the most moving chapters is about Paul Fussell, who taught you at Rutgers. You resist using the word “mentor,” preferring instead to use “teacher.” How did he influence your life?

Fussell’s best writing is about war. In basic training, he, for the first time in his life, met people who worked for a living. The working-class sergeant who mentored the young rich boy—Lt. Fussell—died next to him. Fussell dedicates his book The Great War and Modern Memory to that sergeant. At Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, Fussell taught a wonderful honors section of English composition. Along with poets Henry Dumas, Robert Maniquis, and Peter Najarian, I was a student in that class. I think we benefited from his sense of mission.

BU Today: You conclude by talking about the Favorite Poem Project. Why does that project remain so dear to you? What did it do for poetry?

The project is patriotic: the Cambodian-American kid reading Langston Hughes, the glassblower reading Frank O’Hara, the Jamaican immigrant reading Sylvia Plath, the construction worker reading Whitman—they visibly, audibly, fulfill certain ideals of mine.

Robert Pinsky will read from Jersey Breaks tonight at 7 pm at Grolier Poetry Bookshop, 7 Plympton St., Harvard Square, Cambridge. The reading is both in person and virtual. Register here.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.