Game of Thrones and What It Can Teach Us about Historic European Power and Politics

CAS course offers a scholarly take on the fictional continent of Westeros

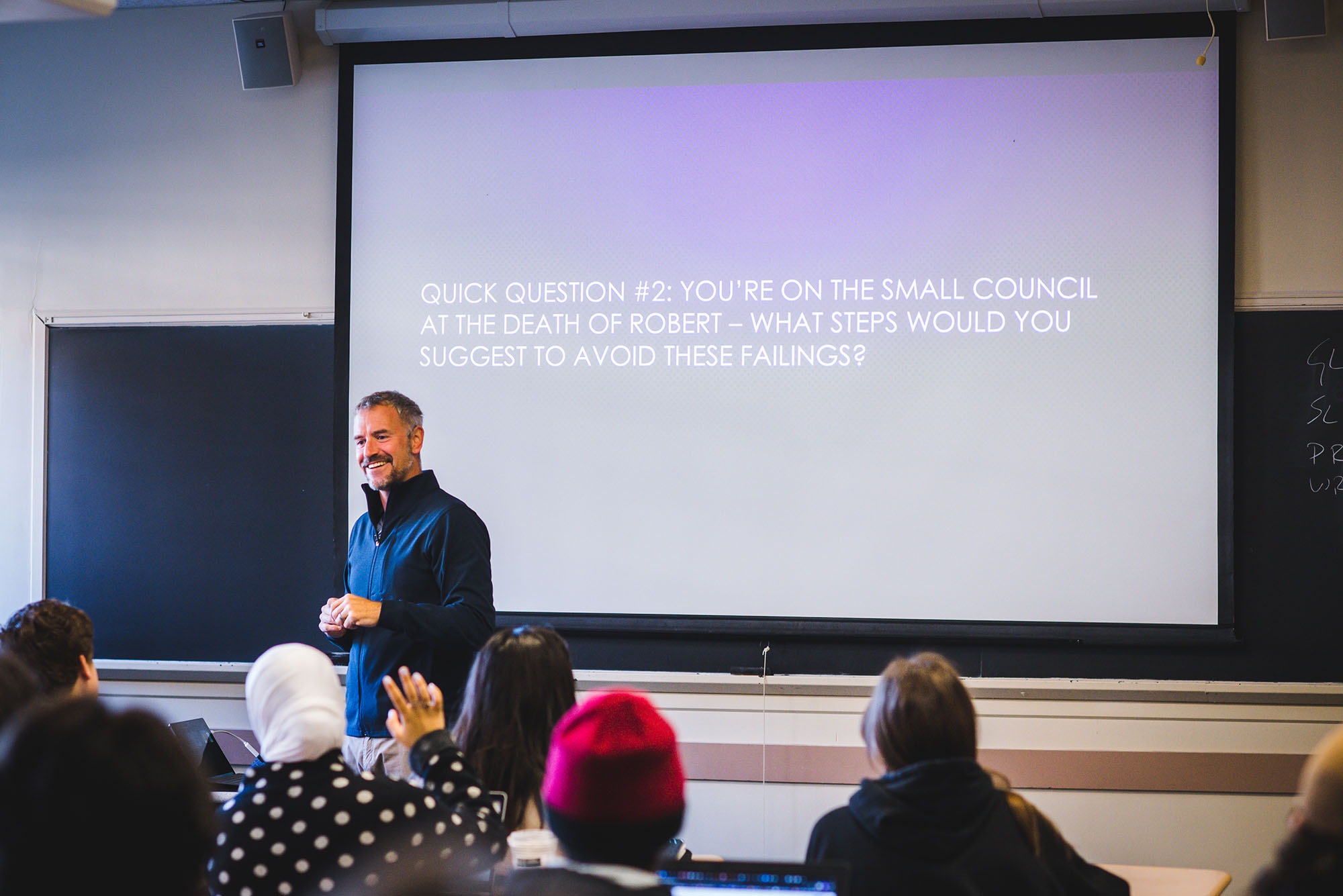

“I myself have to balance my fandom with my intellectual approach,” says Phillip Haberkern, a College of Arts & Sciences associate professor of history, who designed the CAS history class Game of Thrones: Power and Politics in Pre-Modern Europe.

Game of Thrones and What It Can Teach Us about Historic European Power and Politics

CAS course offers a scholarly take on the fictional continent of Westeros

Season one of House of the Dragon may have wrapped Sunday night, but the talk about Westeros continues several times a week for the students taking the new College of Arts & Sciences history class Game of Thrones: Power and Politics in Pre-Modern Europe.

The course challenges students to study the five main issues raised in author George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series, which HBO’s eight-season Games of Thrones series was based on: succession, the role of the courtier, hurdles faced by female rulers, moral codes, and the challenges of administering justice. Each week, students are assigned to watch a specific season one Game of Thrones episode, alongside readings and writing assignments.

Students who sign up thinking they will spend the 50-minute lectures discussing fan theories surrounding Bran’s Tower of Joy visit or the conflict between the Children of the Forest and the First Men will be a bit surprised by both the pace and the scholarly direction the class takes. For starters, the course focuses only on the events happening in the show’s first season, so no tearful retelling of Hodor’s origin story or House of the Dragon drama. The students began the semester by reading A Game of Thrones, then switched to pretty hard medieval and early modern sources and political theory (Niccolo Machiavelli, for starters), says Phillip Haberkern, a CAS associate professor of history, who designed the course.

Not all students who take the class go in having read the books or seen the show—Haberkern estimates that about two-thirds of those who signed up are die-hard fans, with the remainder either casual fans or needing the class to fulfill a requirement. He says it’s been an interesting balancing act teaching those two populations.

“I myself have to balance my fandom with my intellectual approach,” says Haberkern, who read the books in the series when they were released from 1996 to 2011, and since then, he says, has been “futilely” waiting for the next book to come out (Martin is infamous for dragging his feet on the final two books in the Song of Ice and Fire series). “The first part of this class is [talking about] how we can take this pop culture artifact as a topic worthy of serious intellectual work. I feel like we’ve done that. Is it great literature? I don’t think so. But is there enough there to raise these really interesting issues that we can then kind of tease out together? Yes.”

Throughout the semester, class discussions explore how different characters are shaped and constrained by the moral codes of their social order, the ways people tried to transform power into rightful authority, and how women assumed authority in a toxic masculine world, among other topics.

Last week, Haberkern asked his students to weigh the benefits and dangers of a hereditary monarchy (one that passes down from parent to child). The homework consisted of two parts: the first was to watch the Game of Thrones season one finale, “Fire and Blood,” which follows the shocking episode where (spoiler!) the honorable Ned Stark is beheaded on the orders of Joffrey, the virulent young king. “Fire and Blood” deals with that fallout and how each character is processing the news.

The second part of the assignment was to read a passage from The Defender of Peace by 14th-century Italian philosopher Marsilius of Padua. Throughout history, both western and eastern scholars wrote a genre called Mirrors for Princes—textbooks of sorts that instructed kings and rulers on governance and behavior, and The Defender of the Peace is considered part of the genre.

On this day, Haberkern stands at the front of the class and asks students why some may make the argument for a hereditary monarchy, based on their reading. Their reasons include that a king will care more about a kingdom because he will want to pass it on to his children in good shape, the difficulties that would arise if a king was elected (since electors would want to pick someone they can manipulate), and the 20-or-so years needed to properly educate and prepare a prince to rule. One student suggests that a benefit of a hereditary monarchy is that the next in line would be a known quantity. “What if they’re a total shit show like Joffrey? You can plan. Better the devil you know!” Haberkern says to laughter. With class time running out, he tells the students the next class will deal with the negatives of a hereditary monarchy.

Haberkern, a historian of late medieval and early modern Europe, describes the Game of Thrones world as a “pastiche,” with no perfect historical correlation. There are pieces of 15th-century England (think Wars of the Roses), but in terms of technology, warfare, and government organization, he sees similarities to the 12th or 13th centuries. Some days the class talks about the actual historic phenomenon behind a plot point in the book, other days they discuss how reading these medieval and early modern authors helps them understand those issues in a more substantial way.

Haberkern spent several years toying with the idea for this class. Then, in 2021, he was teaching a grad-level pedagogy class and gave his students an assignment: write a syllabus for a fictional class. He used the opportunity to finally write the syllabus for Game of Thrones: Power and Politics in Pre-Modern Europe and then submitted it for department approval. His plan right now is to teach it once a year, and he says it should be a Hub course by next fall.

Students have the chance to flex their creative muscles in the course writing assignments, as Haberkern has designed them so his students can apply the lessons from the readings to the circumstances of the book characters. He writes in the syllabus: “While our assignments will be linked to the narrative within our fictional source material, our interpretations will always be grounded in the insights of actual historical thinkers, both modern and medieval.” Those assignments take the forms of poems, songs, and a brief to the king, with a prompt like this: “Pretend you are a maester working in the court of King’s Landing, and you must send out the ravens announcing Joffrey’s ascension to the throne. In a royal decree, justify why Joffrey is the best person for the job, drawing from writers such as Marsilius.”

Never having read the books, and only a casual watcher of the show, Silvano Spagnuolo (COM’26) is now hooked. His favorite assignment thus far: writing a ballad about Jamie Lannister and explaining why he believes the knight best codifies the idea of chivalry.

“I want to see this class applied to every single fandom,” he says. “The class is so fun, and [Haberkern’s] passion is so infectious, it makes you ridiculously engaged in the actual history.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.