Celebrated Abstract Artist and Alum Brice Marden Dies

His paintings are held in museum collections around the world

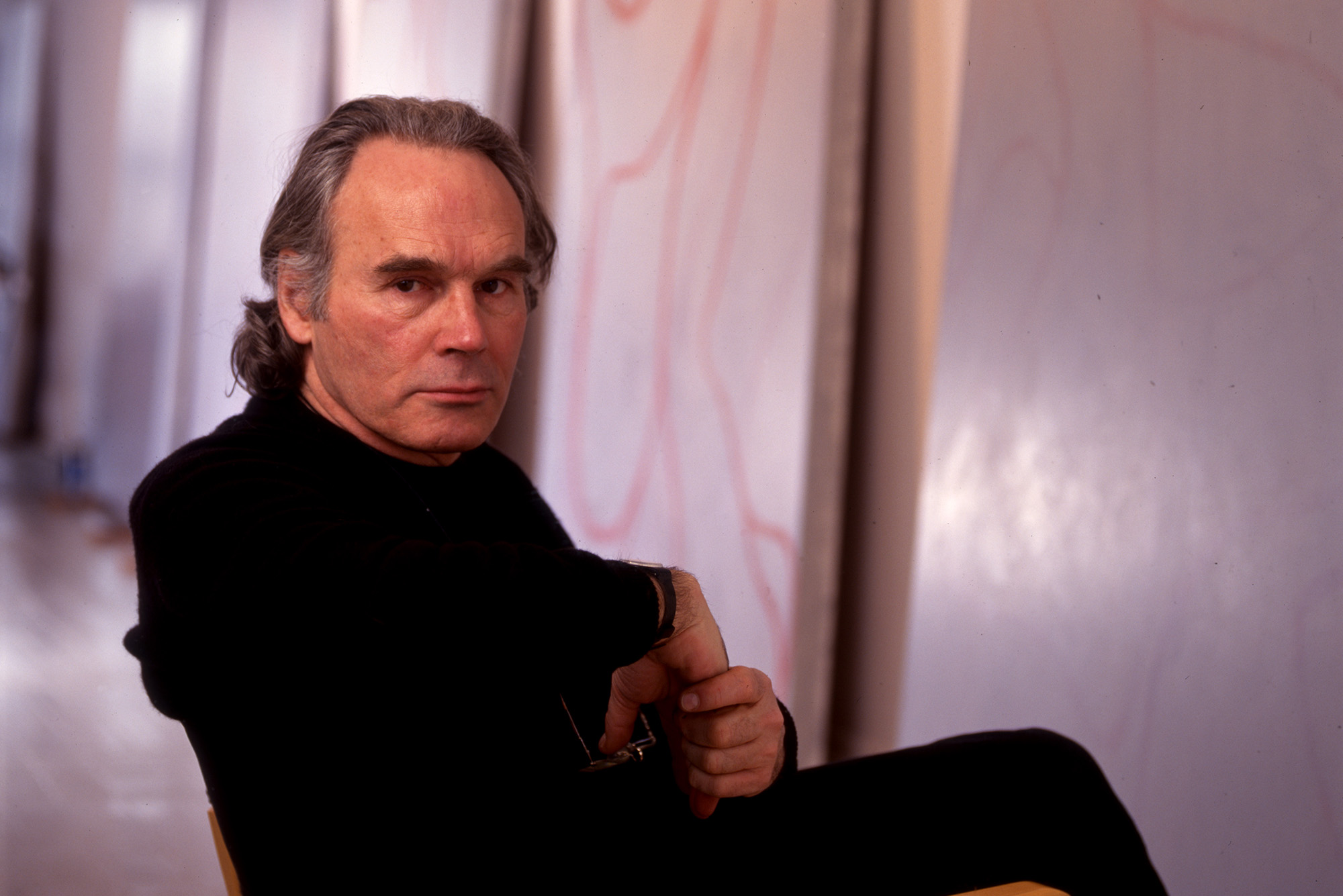

Painter Brice Marden (CFA’61, Hon.’07) in his studio in New York City on January 15, 1998. Photo by Vernon Doucette

Celebrated Abstract Artist and BU Alum Brice Marden Dies

His paintings are held in museum collections around the world

In the days after acclaimed abstract painter Brice Marden died, appreciations and superlatives poured in from around the world. He was “one of the most admired and influential artists of his generation” (New York Times), a “visionary” (Vogue), and “a master of color, light and texture” (Washington Post). Marden (CFA’61, Hon.’07) “produced a body of work of profound beauty and intelligence” (Museum of Modern Art) and “pathbreaking explorations of gesture, line, and color that put him in a category of one” (Artforum).

Marden’s career spanned nearly 60 years, and his works are held in museum collections around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Tate Gallery in London, and the Kunstmuseum Basel in Switzerland. In 2019, the Times proclaimed him “America’s grand old master painter.”

Marden died of cancer August 9, 2023. He was 84.

Dana Clancy, director of the Boston University College of Fine Arts School of Visual Arts, says she last saw Marden’s paintings in 2019, at a powerful exhibition at Gagosian Gallery in New York, which represented the artist. “It’s hard to use words to describe such materially rich abstract paintings as Marden’s, and it is even difficult to understand their power when only seeing them online or in a book,” says Clancy (CFA’99), a CFA associate professor of art. “I went to see the exhibition because the works really function as they are meant to only when seen in person.

“With Marden’s paintings, a viewer doesn’t stand still looking—the paintings suggest that one move from far to near to look more closely,” Clancy says. “Our movement as viewers in the gallery seems invited by—or echoes—the painter’s quite physical process. Marden painted and moved across his studio space as he worked, using long-handled brushes or sticks as tools, as well as working the surface by scraping it.”

Clancy says she perceives a change in the paintings as she edges closer: “Layers of added and scraped-away wax-based encaustic paint reveal new relationships in paint, color, mark. The longer you look at this work—that at first glance can seem as simple to describe in language as colors and lines—the more you see.”

Learning the Fundamentals at BU

Born in New York, Marden attended Florida Southern College for a year before transferring to BU. In a 1998 Bostonia profile, he told art critic and writer Phyllis Tuchman (DGE’66, CAS’68) that he received a grounding in the fundamentals at the College of Fine Arts, and was “made aware of the tradition of being a painter.”

Tuchman wrote, “One of America’s most accomplished abstractionists still remembers how thorough his education was, including drawing from the model and other kinds of figure studies…. Moreover, his classes in theoretical color were combined with realistic color observation from the future. The young artist didn’t balk at these conservative practices: this was the legacy he was inheriting. But he stopped making nudes when they were no longer required. Marden unequivocally states, ‘I always wanted to make abstract art.’”

Two CFA faculty members in particular had an impact on Marden. One, according to Clancy, was Reed Kay, now a professor emeritus, who taught the materials and techniques course and who had studied with artist Karl Zerbe. (Marden, the college’s convocation speaker in 2007, invited Kay to the event.) “Marden also spoke about being quite influenced by working with graphic design professor Arthur Hoener,” Clancy says, “whose work with calligraphic marks and grids perhaps also helped set this artist as a youth on a pathway to developing his specific and groundbreaking painting processes, which have in turn influenced so many painters and artists.”

After graduating from BU, Marden earned a master’s degree at Yale. He moved to New York and took a job as a guard at the Jewish Museum, where he was able to study Jasper Johns’ work during a museum retrospective. It was “an influential moment for the young Marden,” according to Artnet News.

Not long after, he had his first solo show, in 1966, at the Bykert Gallery in New York. “With painting decidedly out of vogue, reviews for this inaugural outing, featuring thickly painted surfaces blended with turpentine and beeswax, were mixed,” according to Artnet News. “Undeterred, Marden, by now working as a studio assistant for Robert Rauschenberg, slowly made a name for himself with large, often monochromatic canvases featuring flat, rectangular panes of color.”

Marden’s New York studio, photographed in 1998. Photos by Vernon Doucette

Marden was credited with rejuvenating painting at a time when the art world had largely shifted its attention to pop art and conceptual art.

His technique shifted in the 1980s. Influenced by Chinese calligraphy, he began painting with longer brushes, from farther away. In a 2015 conversation with his daughter Mirabelle for Interview magazine, he described his technique: “When you’re using a long brush, you have your arm at full length. Basically, it exaggerates the movement of your body. But I always start far away and end up really close. Usually, when I am drawing, say with a brush from a distance, I always close in on it and I end up working it with a knife, so every inch of surface gets touched by this little knife. It’s like going from the vague to the specific—closing in on it, focusing.”

By 1998, Tuchman wrote in Bostonia, Marden’s work projected “a subdued and quiescent character. This became apparent a few years ago when the Tate Gallery in London mounted a survey of the artist’s much-sought-after, pricey prints, including several executed when Marden was still a student at Boston University. At about the same time, to publicize an exhibition at the Louvre featuring old masters and young Turks, a poster of one of Marden’s singular diptychs was plastered all over Paris.”

Tuchman described Marden as “unimpressed by his recent critical successes.” She noted in the 1998 profile that one of his drawings, purchased for $260 in 1969, had sold for $380,000 at a Christie’s auction. Later in his career, his works sold for millions; in 2020, his painting Complements went for $30.9 million at auction. At the time, the New York Times wrote, “Such are the dynamics of the market for contemporary art that auction prices for Mr. Marden are now almost as high as those for an old master like for Rembrandt.”

News reports about Marden’s death noted that he was still painting a few days before he died.

In a 2014 video from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Marden described the pull of abstract art. “I have always just felt that abstract painting—if one chooses to look at paintings as vehicles to take you to some other place—that the abstract painting was much more open, and therefore could take you to more complicated places. Abstract painting may have a lot of references to the real world, but they’re not specific and they’re not involved with a narrative and they’re not telling you so much what to do. I find it very interesting how I keep thinking about it all the time. I keep thinking about how to look at paintings, what’s going on in the painting. That’s why I’ve always really believed in the strength of abstract painting.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.