Everything You Need to Know about Narcan

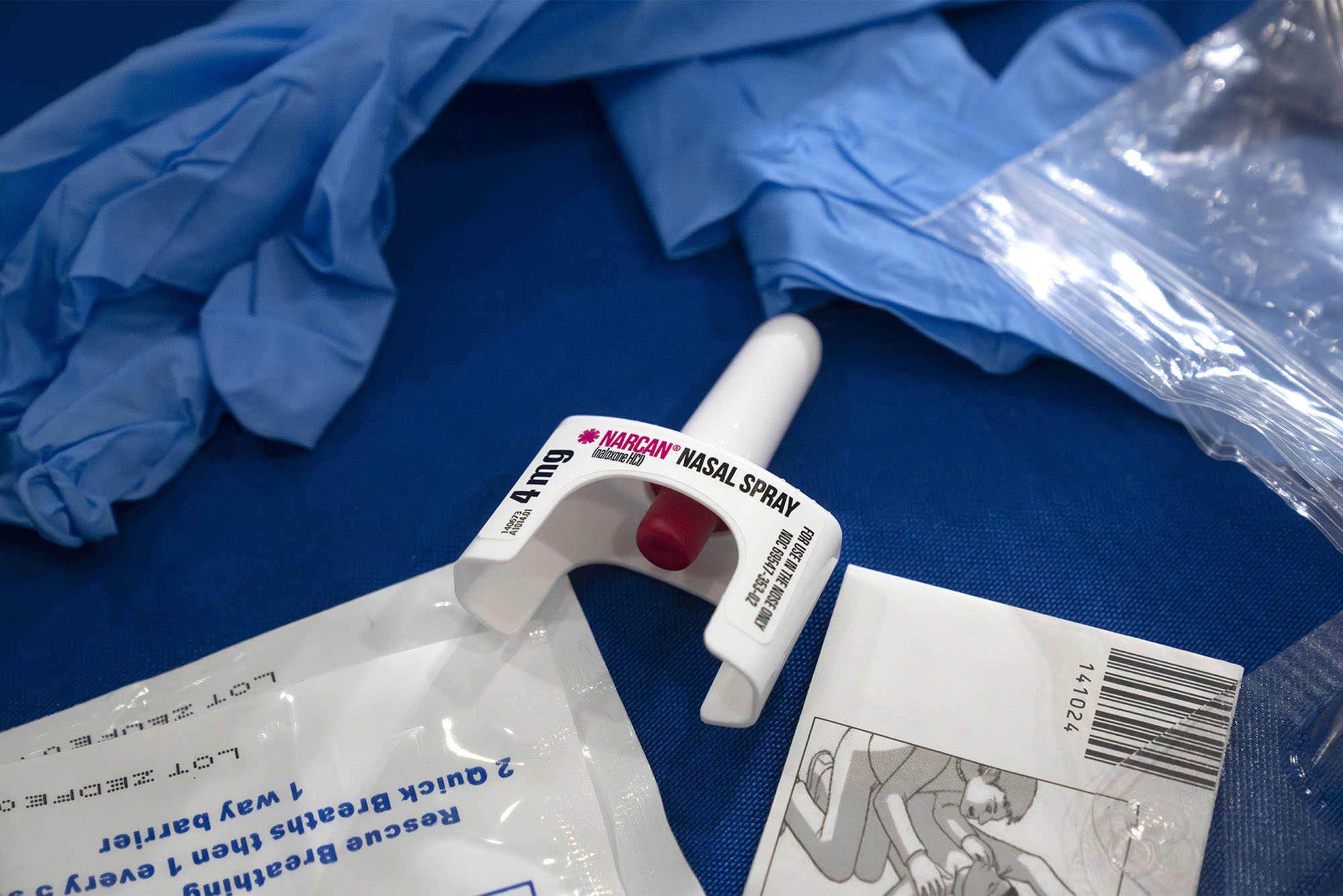

Narcan, the nasal spray that reverses the effects of an opioid overdose, is now available over the counter. Here’s everything you need to know about how to use it. Photo by AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein

Everything You Need to Know about Narcan

Now that the anti-overdose nasal spray has been cleared for over-the-counter sales, a primer on where to find it and how to administer it, plus info on addiction services available at BU

In March, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Narcan for over-the-counter (OTC) sale.

The anti-overdose nasal spray, a form of naloxone, has long been hailed as a “wonder medicine” for its ability to reverse the effects of opioid overdoses within minutes. As the opioid crisis continues to take a deadly toll across the United States—according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 220 people died of an opioid overdose every day in 2021—Narcan is a tool that everyone, not just medical professionals, can keep in their arsenal.

Now that Narcan has officially hit shelves, BU Today reached out to Boston University addiction expert Alexander Walley (SPH’07), a professor of medicine at the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center, and harm reduction expert Thomas Regan (SPH’23), a program specialist for King County Regional Homelessness Authority in Washington state, about Narcan—what it is, how to use it, and where to find it.

Plus: we have info about addiction services at BU.

In addition, Student Health Services and the Faculty & Staff Assistance Office are hosting free virtual Overdose Prevention Trainings, led by Regan on Friday, October 26, and Friday, November 17. The one-hour trainings are available to all BU students, faculty, and staff.

NARCAN 101

Drug Chemistry

What is Narcan?

Photo by AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein

Narcan, a nasal spray, is a form of naloxone, a drug that reverses the effects of an opioid overdose. Narcan is a brand-name drug; there are also generic naloxone nasal sprays. Naloxone also comes in an injectable form.

Naloxone, which was first patented in 1961, is what’s called an opioid antagonist. It functions by blocking the brain’s opioid receptors and displacing any active opioids from the receptors, counteracting life-threatening depression of the central nervous system that high doses of opioids can cause.

Naloxone is nonaddictive and works only when someone has opioids in their system. It’s impossible to overdose on naloxone and the drug won’t cause any harm if administered to someone who doesn’t have opioids in their system.

What are opioids?

Opioids are highly addictive pain-relieving drugs with origins in opium. Some drugs are made directly from poppy plants and others are made synthetically in labs using the same chemical structure. Opioids can cause feelings of relaxation and euphoria in addition to pain relief. Common opioid-based painkillers include codeine and brand-name prescription drugs OxyContin, Vicodin, Percocet, and Oxycodone. Heroin and morphine are also opioids.

Some history: the opioid crisis began in the 1990s with the overprescribing of prescription painkillers like Oxycodone. In recent years, opioid deaths have been fueled by the rise of fentanyl, displacing heroin—which had displaced prescription painkillers in a “second wave” of the opioid crisis—as the leading cause of overdoses. Also in recent years, tighter laws meant to counteract the overprescription of opioids have made it harder for some chronic pain patients to access their pain medication. It’s not uncommon for patients to turn to street drugs instead.

As the Washington Post writes, “data confirms what’s long been known about the arc of the nation’s addiction crisis: Users first got hooked by pain pills saturating the nation, then turned to cheaper and more readily available street drugs after law enforcement crackdowns, public outcry, and changes in how the medical community views prescribing opioids to treat pain.”

What is fentanyl?

Fentanyl is a common synthetic opioid that is 40 times more potent than heroin, and 100 times more potent than morphine, Walley says. It’s often used by street-drug makers to “cut” their products—such as heroin or counterfeit prescription painkillers—because it’s less expensive to manufacture than opioids that need to be derived from poppy plants. It’s also used on its own. Fentanyl is now the leading cause of death for Americans aged 18 to 49.

The problem with fentanyl is not only that it’s highly potent, but it’s fast-acting. Fentanyl is what we call “lipophilic, which means it crosses the blood brain barrier very fast,” Walley says. “‘Lipophilic’ itself means it likes fat—and there’s a lot of fat tissue in the brain.”

That all means it’s very easy to overdose on even small amounts of street drugs that contain fentanyl, Walley says. He also points to what experts call the “chocolate chip cookie effect,” where just like chocolate chips in a cookie, fentanyl might not be evenly distributed from batch to batch of a substance. Because you never know the exact chemical composition of what you’re receiving, it can be extremely difficult to predict what dosage may cause an overdose and what might not.

Overdoses

What is an overdose?

An overdose happens when someone takes too high a dose of a substance. With opioids, Walley says, “at high doses they can cause respiratory depression, which is a slowing of the breathing, and hypoxia, which is a lack of oxygen. Once you have enough of a lack of oxygen to the brain, it can cause people to die.”

What does an overdose look like?

Overdoses present in different ways. Signs include loss of consciousness, no response to outside stimuli, minimal or no breathing, visible difficulty with breathing, vomiting, choking or snore-like gurgling sounds, and fingernails that appear to be blue, purple, or gray. Someone might be awake but unable to speak. People with darker skin may appear gray or ashen, and people with lighter skin may appear blue or purple. Someone may exhibit all or just a few of these symptoms.

It can sometimes be difficult to differentiate between someone who might be overdosing and someone who’s just sleeping, Regan notes. He always advises taking a second to observe if someone’s chest or back is steadily rising and falling—indicating regular breathing—before proceeding to administer Narcan.

Where can you find Narcan?

The easiest way to get it is to buy it from a pharmacy. Narcan is now available at Massachusetts pharmacies without a prescription. Go to the pharmacy counter and tell the pharmacist that you want a box of Narcan, which comes with two 4-milligram doses. You can pay out of pocket or use your insurance (you’ll have to pay any associated co-pay costs). Narcan can cost anywhere from $40-$80 out of pocket. Some insurance providers—including BU’s student and faculty and staff plans—cover the cost completely.

If you have questions, you can always call your insurance company or local pharmacy for more information.

What do you do if you’re with, or find someone, who you think overdosed? And how do you administer Narcan?

There are a set of steps that experts advise, Regan says.

First: try to stimulate them awake. Loudly call out to them and if that doesn’t work, tap them on the shoulder. Then, use your knuckle to vigorously rub up and down their breastbone—an uncomfortable sensation that should provoke a response in a conscious person, Regan says. If there is no response, call 911 and tell them you’re with someone who isn’t breathing. (If you’re on the Charles River or Fenway Campus, you can also call BUPD at 617-353-2121. On the Medical Campus, call BU Public Safety at 617-358-4444.) Then, when you know emergency services is on the way, administer Narcan.

Narcan functions like any nasal spray—place it fully inside their nostril, then press the pump. Remove the pump from their nostril. Naloxone can take a few minutes to take effect. In the meantime, perform rescue breathing (Regan advises carrying a CPR face shield or mask in addition to Narcan) until the individual wakes up or begins breathing again. If they don’t wake up or start breathing after two minutes, repeat the process: administer Narcan in their other nostril and perform rescue breaths for an additional two minutes. Repeat as needed until the person wakes up and starts breathing or emergency personnel arrive.

If a person wakes up before emergency response gets there, place them in recovery position.

A few things to note: first, an overdose is an event that requires emergency-speed response, Regan says, regardless of personal feelings about calling 911. Oftentimes, the operator can also walk you through what to do while you wait for medics to arrive. And: if you do not know if the person you’re with has been using drugs, it is not necessary to tell the operator that you suspect an overdose. If you do know, however, tell them.

Finally, remember that BU’s Good Samaritan Policy applies to all campuses and protects BU community members who call for substance-related emergency help. The Massachusetts Good Samaritan Law similarly protects anyone who calls 911 for help.

Where can you access training on how to use Narcan?

There are two free overdose prevention training sessions facilitated by Regan and designed specifically for the BU community, the first scheduled for Thursday, October 26, from 5 to 6 pm, the second for Friday, November 17, from 4 to 5 pm. Find more information and register here.

Regan also recommends watching the video below created by the Boston harm reduction and needle exchange program AHOPE, for an overview on how to use Narcan.

Harm Reduction

What is harm reduction?

In regard to substance use, the “boilerplate” medical definition of harm reduction is a set of clinical practices used to reduce the negative consequences of drug use, Regan says. However, he adds, “I like to call it a praxis that is by the people, for the people,” noting its roots in substance users taking initiative to help fellow substance users from needlessly dying or spreading disease.

Common forms of harm reduction include safe-use sites and needle exchanges, and carrying naloxone. Other examples of harm reduction include infectious diseases testing, vaccination clinics, and safe sex–supply distribution.

Are there ways to make substance-using less risky?

For one, don’t use drugs by yourself, Walley says. “The great majority of people who die from overdoses die alone,” he says. “If you’re with someone else, particularly with someone who is awake and alert, ready to respond, and has naloxone, that’s really important, safety-wise.” If everyone you’re with is planning on using, he recommends taking turns. That applies to all drugs, not just opioids.

If you do use alone, call the Massachusetts Overdose Prevention Helpline, sometimes known as the Never Use Alone hotline, at 1-800-972-0590. The 24/7 hotline connects substance users with trained operators who can call for help in the event of an overdose.

If you are taking substances, should you test your drugs for fentanyl?

Absolutely, Walley says. “If you’re intending to use opioids, you should just assume there’s fentanyl in them,” he says. But other drugs—including cocaine and MDMA—can also be cut with fentanyl and unwittingly put users at risk of an opioid overdose.

Many community organizations, such as AHOPE, distribute fentanyl test strips for free. You can also buy them online from retailers like DanceSafe, Bunk Police, and Amazon.

Addiction Services

What services are available to students at BU?

BU has multiple substance-use and recovery services available to students.

The Collegiate Recovery Program (CRP), run by Student Health Services, is a community of students in recovery from substance use. The CRP supports multiple pathways to recovery, from all substances, with offerings including substance-free events, community networks, and more. New this semester: All-Recovery Meetings, which are offered both in person and online. The CRP can also connect students with resources at BU and beyond regarding substance-free housing, one-on-one support, and other sobriety-focused communities. All of CRP’s services are free. You can fill out this form or email recovery@bu.edu to connect with the CRP.

Behavioral Medicine at Student Health Services can also provide free and confidential mental health services for students who would like to talk about their substance use or that of a loved one or a friend. Students can make an appointment online through PatientConnect or by calling 617-353-3569.

And a local chapter of Alcoholics Anonymous holds weekly meetings at Marsh Chapel on Wednesdays and Fridays at 1 pm. Find more information by calling Marsh Chapel at 617-353-3560.

What services are available to faculty and staff?

The Faculty & Staff Assistance Office can provide counseling services and referrals for faculty and staff who are grappling with their own or a loved one’s struggles with substance use and addiction. The FSAO website also lists additional resources. Contact the FSAO by filling out this contact form, emailing fsao@bu.edu, or calling 617-353-5381.

Faculty and staff are also welcome to attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings at Marsh Chapel.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.