Genealogy’s Golden Age: Alum D. Brenton Simons Is a Leading Champion

D. Brenton Simons (CGS’86, COM’88, Wheelock’94), at home in Boston’s South End, became a member of the New England Historic Genealogical Society as a sophomore at BU. He joined the society as director of education in 1993 and is now the nonprofit’s president and CEO. His own family tree includes Charlemagne and four passengers on the Mayflower.

Genealogy’s Golden Age

Tracing your family tree? BU alum D. Brenton Simons, who heads American Ancestors/New England Historic Genealogical Society, is a champion of the popular activity

Genealogist and historian D. Brenton Simons has spent his career helping people build out the branches in their family trees, but he uncovered some colorful surprises when he put a magnifying glass up to his own. His illustrious forebears include Charlemagne, William the Conqueror, and four Mayflower passengers. More recent relatives were part of the infamous Dalton Gang, who in the 1890s robbed trains and banks throughout Kansas.

That last ancestral connection especially tickles Simons (CGS’86, COM’88, Wheelock’94), the long-time president and CEO of American Ancestors/New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS). Founded in 1845, the society is the country’s oldest and largest genealogical organization (American Ancestors is the global brand). “To me, it’s a fascinating connection to the Wild West,” says Simons, “but to someone like my great-uncle—who I mentioned this to at his 90th birthday party—it was a source of embarrassment. In my experience, most people are fascinated by these things.”

Since joining NEHGS in 1993 as its director of education, Simons has held almost every position in the nonprofit and has worked to transform it into one of the world’s top destinations for family history research. As president and CEO, positions he took on in 2005, he has helped raise more than $100 million for the society and seen its membership grow to 400,000 people. Millions more visit its website to access the 1.4 billion names in the databases. Its Boston office, on Newbury Street, is the anchor location of the popular PBS series Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., which is famous for bringing celebrity guests to tears with moving—even shocking—revelations about their family trees.

Gates, the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard University, describes Simons as a champion of the field.

“It seems to be that one consistent pattern in Brenton’s leadership has been opening the doors of the vaults of genealogy to the American people, so that people understand that genealogy is for everyone,” Gates says. “Everyone descends from ancestors. And those ancestors are in suspended genealogical purgatory waiting to be discovered. He’s the perfect leader of the leading genealogical society in the United States.”

Gates is an honorary trustee of NEHGS and serves on the advisory board of the recently launched 10 Million Names initiative, which aims to recover the identities of the 10 million people enslaved in America before emancipation in an effort to find their living descendants. The launch was spearheaded by Ryan J. Woods (Wheelock’05,’06), executive vice president of NEHGS. Researchers say much of the project will rely on gathering oral histories and accessing previously undiscovered materials, such as family trees found in bibles.

Much of Simons’ free time, not surprisingly, mirrors his professional passion. He is president of the American Friends of St George’s Chapel & the Descendants of the Knights of the Garter, an organization that helps to financially support and volunteer at St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle and its surrounding buildings. He’s received many honors for his nonprofit leadership work and guidance in the fields of genealogical research and history, including the first-ever John Adams Medal from the Sons of the Revolution in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the Bradford Award from the Pilgrim Hall Museum in Plymouth, Mass., for his work in commemorating the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the Mayflower and promoting the history of the indigenous Wampanoag people. He’s written books, including Witches, Rakes, and Rogues: True Stories of Scam, Scandal, Murder and Mayhem in Boston, 1630–1775 (Commonwealth Editions, 2005).

Historian and author Doris Kearns Goodwin says Simons’ dedication to the study of family history “has not only helped educate and inspire countless historians and authors like me, but has also had immeasurable impact on millions of people who seek to learn about their past and make connections to today.”

Bostonia spoke with Simons about why people are fascinated by their family histories, the field’s Brahmin roots, and how genealogy combined with DNA results can lead law enforcement to big breaks in previously unsolved cases.

Q&A

With D. Brenton Simons

Bostonia: When did your interest in genealogy start?

Simons: I was lucky because all four of my grandparents were very interested in history and genealogy. And I love hearing the family stories. And so, late in their lives, I was able to go to NEHGS while I was at BU and do research on our families and share it with them. And now, as I look back, I’m so glad I could do that and connect with them about something they cared about, and I cared about too.

Bostonia: Why was the NEHGS formed, and why in Boston?

Genealogy is one of the most popular activities in the world. Recordkeeping started here in New England, at the very first moment; town records of births, marriages, and deaths proliferated. So, if you have New England ancestry, it is generally because those records provide a very fruitful experience. In other parts of the country and other parts of the world, record sets are sometimes missing, damaged, or destroyed, or were not kept. So, it was natural that this area realized first that we could use these records to create lineages, and that was really the founding of the institution.

There were great institutions in Boston, such as the Boston Athenaeum, the Massachusetts Historical Society, and universities. So, Boston was a center of learning and a natural place for an institution like this to spring up. And our founders realized that records were not being preserved and that people were curious about their roots.

It’s important to note that this is not just a white Anglo-Saxon activity. I’ve been excited to help research Irish, Italian, Jewish, and African American [ancestries] and push for more work in those areas.

One of the exciting ways in which we do that is we work with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., who is a board member of the society, and do all the fact-checking for Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates, Jr. What “Skip” Gates does so well is show the unlikely pairings of how people are related to each other, how we are all related to each other. We love being a part of something like that.

As we approach our bicentennial [in 2045], we’re communicating with people of different backgrounds. And one of the things happening now is that we purchased the adjacent building on Newbury Street and are reconstructing that building. Our new “discovery center” will have families and children come to learn something of their history, aimed at an ethnically diverse audience. The new building will show the science and technology aspects of what we do, because we do so much work involving DNA.

Bostonia: How has the field changed, with the development and expansion of DNA testing?

Obviously, that’s huge. DNA tests are phenomenal for genealogy and genetic genealogy, which is used in solving crimes. I give talks on it all the time. It was used in solving the Golden State murder case [the serial killer who murdered more than a dozen and raped more than 50 people in California in the 1970s and 1980s] and in many, many other cases. And for the average genealogist, it’s an important tool in your tool kit because it can help solve problems, even those centuries or generations old.

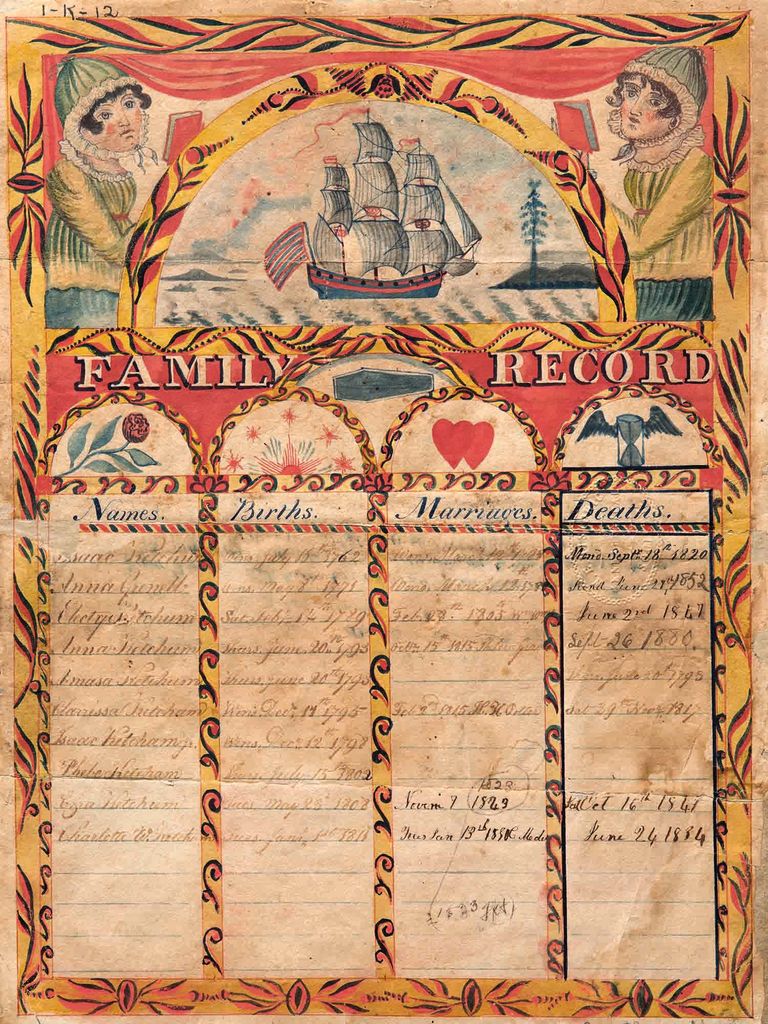

The NEHGS collection, one of the largest in the country, includes manuscripts from the 14th century and many primary source documents, like this family record. Courtesy of NEHGS

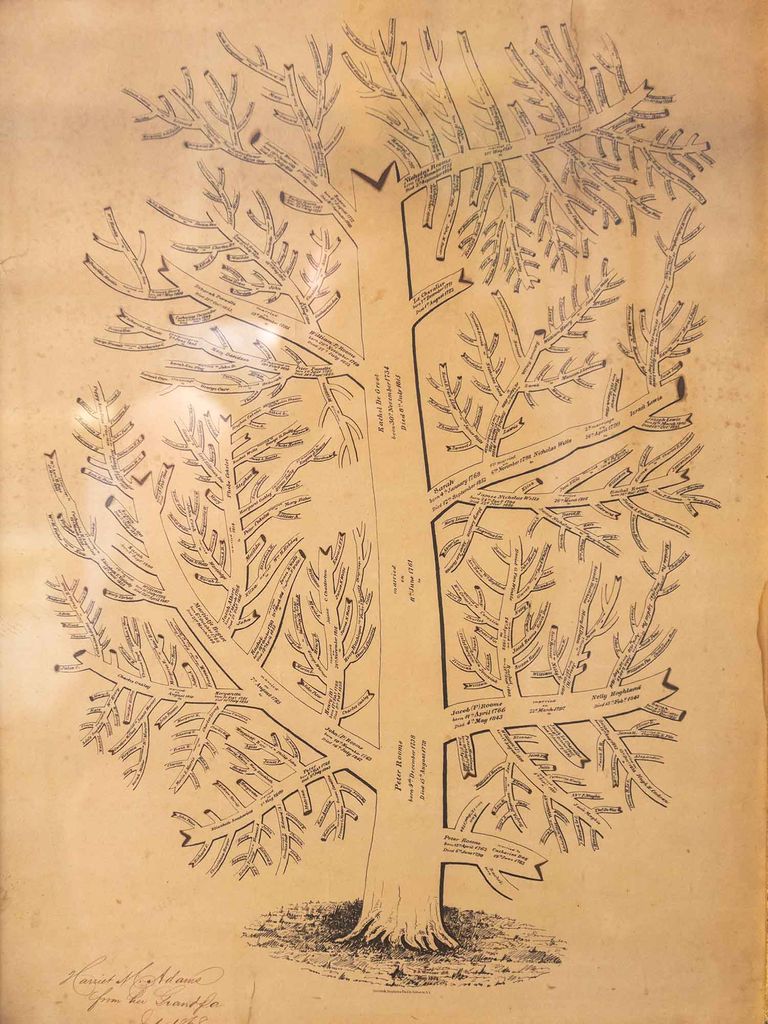

Simons’ lithographed family tree was created by his great-great-great-great-grandfather. Courtesy of NEHGS

One of the things that my staff does is work on special projects. You might have the proverbial three brothers who came to the US together, and their descendants want to figure out whether they actually came together. Were they brothers? And about half the time, these things are correct. And the other half of the time, we find out that something else happened. We can use DNA testing as a diagnostic tool when it comes to questions in genealogy. Obviously, another use is for paternity questions.

So, I call this the golden age of genealogy. Today, records are available that you couldn’t have put together in a whole lifetime of going around to courthouses and other repositories. Now, vital records, probate, deeds, DNA results—the things that are online are so amazing. And one of the ways in which we’ve responded to this as an organization is to provide services to help people find these [records]. If they want to figure out whether this was a myth, we’re able to help. We provide services and are not just a passive library, which we were 20 years ago.

Bostonia: If someone tells you they’re going to take a DNA test, do you ever say, “You might want to think first about what you’re going to find”?

In my experience, most people are fascinated by those things. Unless [a finding] involves them personally or a parent, and they feel they have to be discreet about the information or reveal something they don’t like, people usually are fascinated.

I’m thinking of an example—a lot of people discover their mother or father married and divorced someone and just never mentioned it. So, after their death, they find out that their parents had another marriage or even another family. That is the kind of thing that can stir up emotions.

But what I tell people is kind of the opposite: if there are things that are potentially embarrassing for your family, it’s better to tell them now. A DNA test will reveal things, and you can’t control whether someone else is taking a test or not [and your family discovers the outcome]. Better to have these conversations rather than someone being surprised through a DNA test.

The norm on DNA testing, in the vast percent of cases, is just to discover your maternal or paternal haplogroup [a genetic population with a shared ancestor]. Then the ethnic and national numbers are based on probability models. And I tell people also to go back every six months and look, because your numbers will have shifted.

Bostonia: Oh, that’s interesting.

You’ll be more Scottish this month and more French next year. You just don’t know because, obviously, the results are being refined; the more people take a test, the more data is collected, and it does shift things. A lot of modeling goes on there.

Bostonia: Genealogy is used to solve decades-old mysteries—like the Golden State murders.

Yes. For instance, my staff worked on the Lady of the Dunes murder case in Provincetown a few years back. [The murder of a woman found in the dunes of Provincetown, Mass., was solved in 2023, after almost 50 years.] One of the ones I loved was the case of Richard III, exhumed from a car park in Leicester, England. I know the archaeologists who did that, and [Richard III’s descendants were traced] genealogically [with the help of DNA samples].

I have a slew of cases I give lectures about around the country where some long-standing mystery has been solved using DNA and genealogy. You can’t just do the DNA without genealogy. Both disciplines come into play.

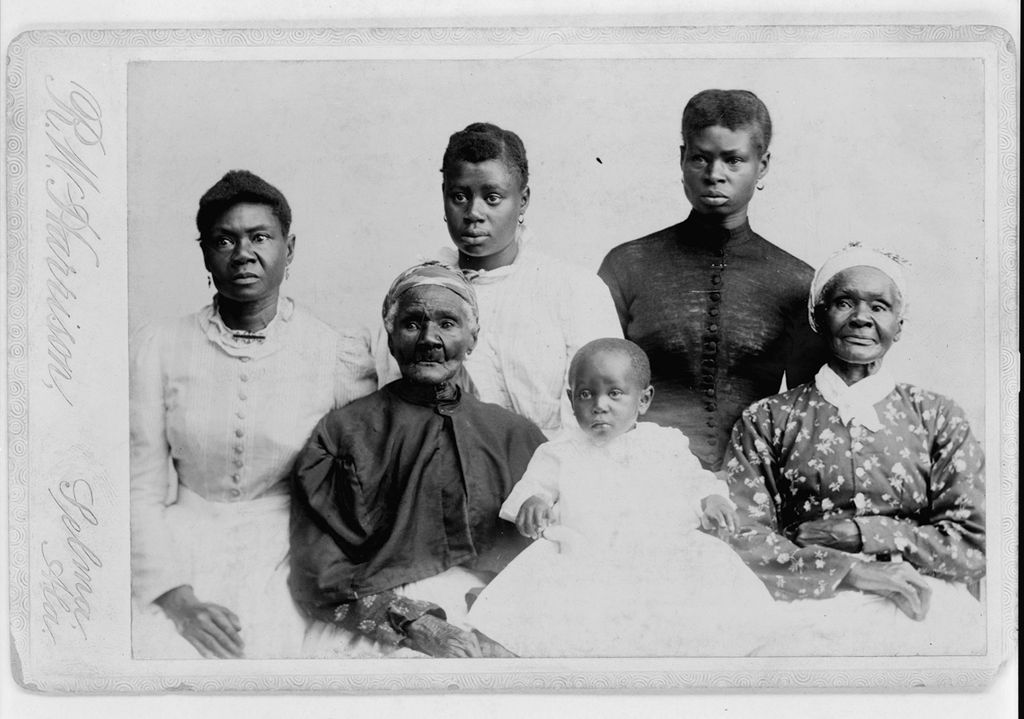

The NEHGS 10 Million Names project aims to document and trace the descendants of the approximately 10 million individuals enslaved in America from the end of the 16th century through emancipation. Photo by R. W. Harrison, Six Generations, Selma, Ala., ca. 1893. Library of Congress

Bostonia: Tell us about the 10 Million Names project.

What we plan is the most ambitious African American research project of its kind ever undertaken. And it is essentially this: to take the approximately 10 million individuals enslaved in America from the end of the 16th century through emancipation, document them, and trace their descendants. There has never been a systematic study like this. The idea behind it, at least in part, is to provide heritage, legacy, and history to people who are disenfranchised from it. The feeling used to be that African American research was so difficult that you would hit a brick wall right away. By turning it around and going from the enslaved person downwards, we actually can bring a lot of people their family history.

I have to credit my colleague Richard Cellini, who works for us and is director of the Harvard Slavery Remembrance Program. He put together the Georgetown Memory Project, and we’re also helping trace the descendants of the 272 enslaved persons that Georgetown University sold in 1838. When you are in communication with a descendant, there’s this amazing thing that happens, which is suddenly they connect to a story that they didn’t know.

One of the 10 Million Names [honorary] board members is Ketanji Brown Jackson (Hon.’23), an associate justice of the US Supreme Court. When Jackson was nominated [to the Supreme Court], she made a speech at the White House about presumably being the descendant of slaves. Sarah Dery on my research team jumped on this and started looking at her ancestry, and we were able to confirm that there are enslaved individuals in her ancestry.

Bostonia: Why do you think people want to learn more about their family histories?

I think there is an innate curiosity in every woman and man about where they come from and what their legacy will be. Grandparents like to do this with their grandchildren in mind, and people like to do it to explore their self-identity. People do it for connection; they do it for joy. They do it because they like detective work.

For older people, it keeps them mentally engaged and very active doing research. That has many health benefits. And there is data that show that when young people are exposed to family history, it gives them a greater sense of self-purpose. So, as history is taught less in schools, we see this as a great opportunity, and really a duty, to try to put it back. We have an active education program funded by the authors Tabitha and Stephen King; we offer a curriculum to teachers, and kids love this.

The other thing is it’s in no way political; people on both ends of the spectrum see the value in young people learning about history. We don’t color it with opinion, politics, or angles. We simply provide data, and [teach] how to collect it and how to engage in it in ways that we think are constructive. So, there’s this wonderful social benefit to history and to genealogy that is now getting much more attention. And we love that.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.