POV: Revising Roald Dahl’s Classic Children’s Books Is a “Dangerous Portent of Future Censorship”

We can’t and shouldn’t erase all outdated and potentially offensive words from literature

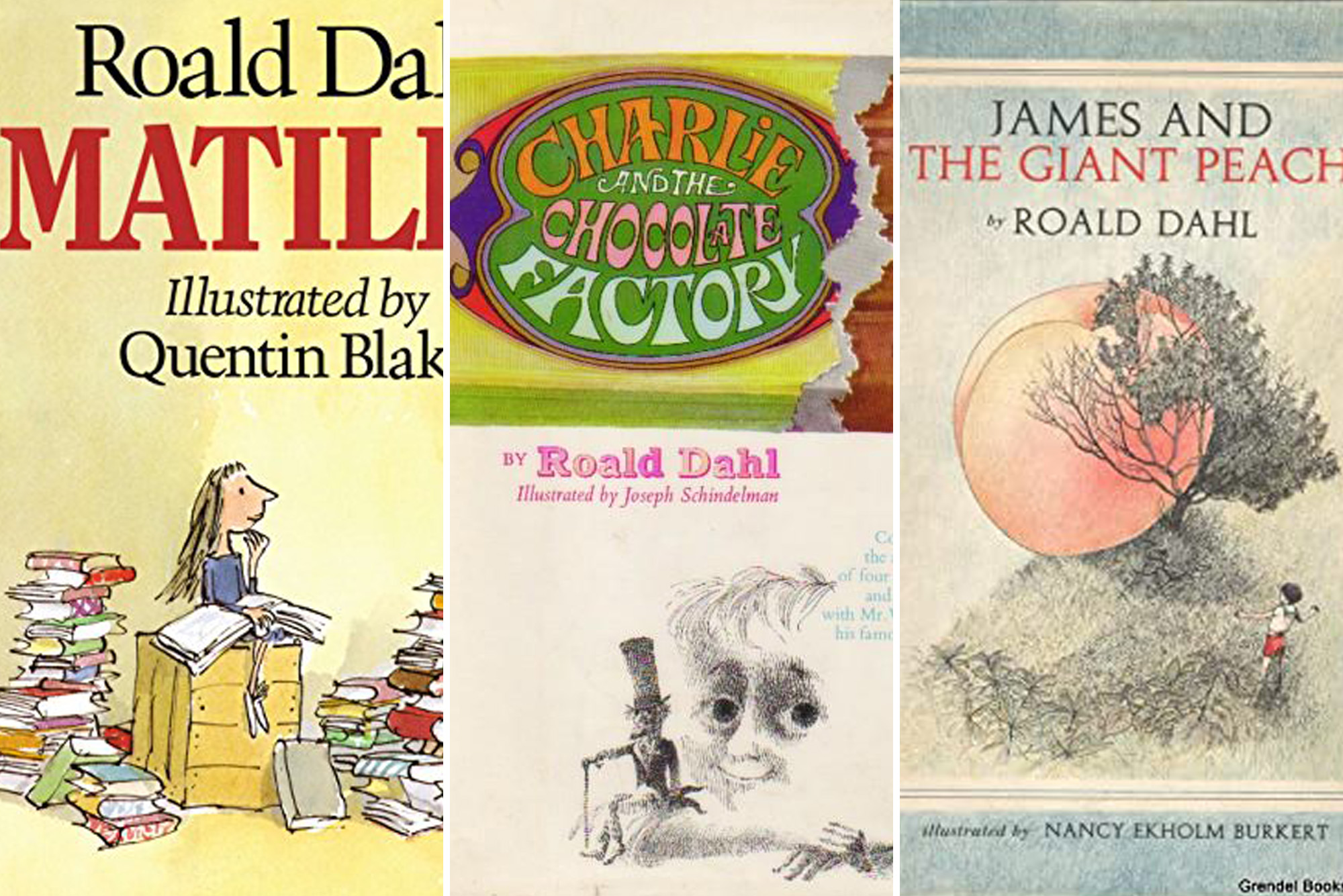

Book covers courtesy of Puffin

POV: Revising Roald Dahl’s Classic Children’s Books Is a “Dangerous Portent of Future Censorship”

We can’t and shouldn’t erase all outdated and potentially offensive words from literature

I’m not Roald Dahl’s #1 reader. As a child, I didn’t find my kindred spirit in Matilda or long to drink from the chocolate river with Charlie. There, I’ve confessed it! But as an author of a children’s book, I cringe at the wide-ranging way that Roald Dahl’s words are now being changed by his publisher.

If this precedent of drastically altering and updating a classic work like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory continues, what words of my own will be in danger in the future? When I work on my next children’s book, will I have to shift from imagining language that will engage young readers to scrutinizing which words might prove objectionable to their parents in decades to come?

Some may wonder: Why all the fuss? It’s just one children’s book author. Why has the Queen Consort of England alluded to the matter publicly? Why has Booker Prize–winning author Salman Rushdie condemned the edits so fiercely? For many who have joined the outcry against the extensive changes Dahl’s publisher Puffin Books announced several weeks ago, it is about more than protecting Roald Dahl and his stories. It signals a dangerous portent of future censorship and a concern about where we will draw the line, especially at a time when censorship of children’s books is often driven by politics.

Part of what’s shocking about the changes to Dahl’s books is how widespread they are. Dahl described the Oompa Loompa dancers in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory as small “men,” but now they are small “people.” Instead of “fat,” Augustus Gloop is now “enormous.”

There are plenty of authors whose works today might be thought of as out of date with today’s mores. Some readers in 2023 might cringe at Peter Rabbit’s mother withholding food as punishment in Beatrix Potter’s tale or at the guns in A. A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh. But these works have been left to stand as they were originally written.

In response to the widespread criticism since the news of the edits broke in mid-February, Puffin announced they will continue to sell the books in their original versions as part of “The Roald Dahl Classic Collection,” but they still plan to publish the heavily revised editions. While this suggests that the publisher and Roald Dahl Story Company—the manager of Dahl’s copyrights and trademarks—acknowledge the public’s desire for access to the author’s original words, the fact that they are still going ahead with the significantly altered editions shows a disregard for the larger concern about censorship.

As a parent, I will be purchasing the original versions of Matilda and James and the Giant Peach for my young children. I don’t believe we can erase all outdated and potentially offensive words from literature. In fact, trying to pretend troubling words don’t exist eliminates opportunities for elementary school children—the targeted age of Dahl’s works—to learn. Talking with children about language in books can be an important moment in their development.

I would also caution against erasing problematic language in Dahl’s fictional stories as a way of somehow correcting or distracting from problems in his real life. He was accused of anti-Semitism and, as a result, has been passed over for national honors, such as being commemorated on a Royal Mint coin, which I think is appropriate. A way to make sense of an author’s complicated legacy is not by conveniently changing his fictional words.

My hope is that we can capitalize on the international attention garnered from this debate about one classic children’s book author to engage in a broader conversation about representation in children’s stories. Instead of changing outmoded words in Dahl’s texts, perhaps future film adaptations of his novels can more effectively bring his stories to diverse 21st-century audiences. I certainly don’t think we should throw away classic texts—even the problematic ones—but we can keep reading the classics while making room for more writers from underrepresented groups.

So, go ahead and pick up a version of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory with the words Roald Dahl actually wrote. And, while you’re at the bookstore, discover a new author too.

Sheila Cordner is a senior lecturer in humanities in Boston University’s College of General Studies and the author of Who’s Hiding In This Book?, a children’s book that introduces young readers to great works of literature and the authors who created them. She can be reached at scordner@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.