Broadway Singers, a Nazi Sympathizer, and the Doomed Flight of the Yankee Clipper

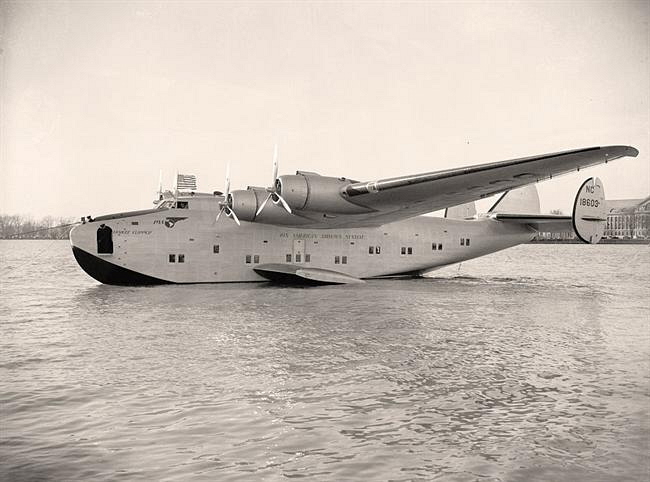

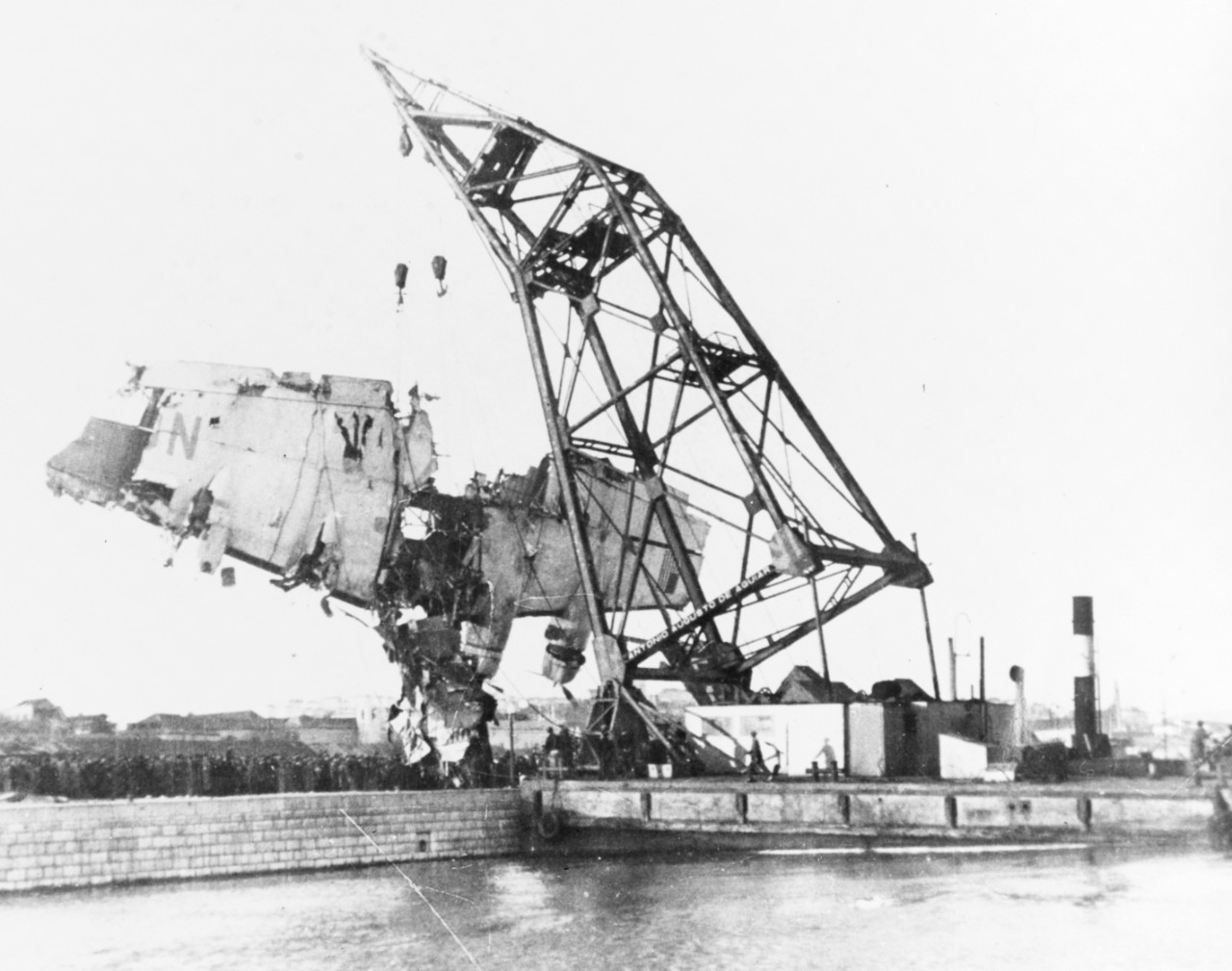

The Yankee Clipper landing in Southampton, England, in 1939; four years later, it would crash on the Tagus River estuary in Lisbon, Portugal. Photo by Ray Illingworth/AP Photo

Broadway Singers, a Nazi Sympathizer, and the Doomed Flight of the Yankee Clipper

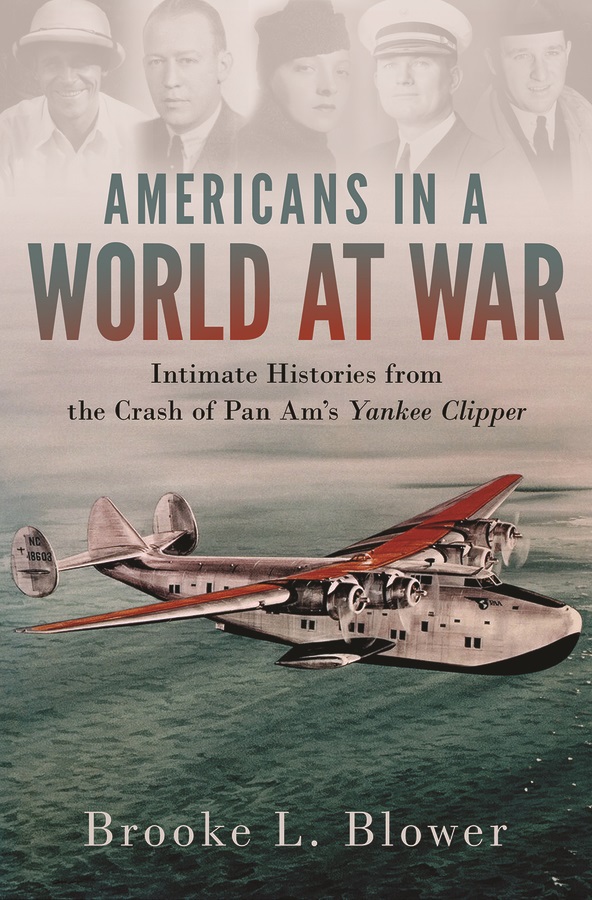

Americans in a World at War by BU historian Brooke L. Blower shines new light on America before and during World War II through the disparate passengers of a 1943 Pan Am flight

Lisbon, Portugal, February 22, 1943. Pan Am’s famed flying boat the Yankee Clipper is cruising in for a routine landing on the busy Tagus River estuary. Despite the light rain speckling the dusky evening skies, the crew of the 42-ton plane can see for seven miles, picking out cutters, fishing boats, and the floating lights guiding them in.

It’s just over a year since the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the Clipper’s motley cast of passengers reflects the precarious state of the world: a United Service Organizations (USO) entertainment troupe, an oilman, a fascist sympathizer, a former Olympian turned war correspondent, a State Department courier, and a dozen incognito US Army officers. At the captain’s wheel is R.O.D. “Sully” Sullivan, the first pilot to log 100 transatlantic flights.

Coming in at 135 knots and at about 500 or so feet above the surface of the river, the Yankee Clipper begins a banking, descending turn. It will be the plane’s last controlled movement. As it edges lower, the left wing tip hits the water, flinging the Boeing 314 into the Tagus. After 10 excruciating minutes lying partially submerged, the Yankee Clipper—the plane that inaugurated scheduled transatlantic passenger flights, that had been christened by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt just four years earlier—sinks below the surface.

Of the 39 passengers and crew on board, only 15 would survive.

In her new book, Americans in a World at War: Intimate Histories from the Crash of Pan Am’s Yankee Clipper (Oxford University Press, 2023), Boston University historian Brooke L. Blower recounts the tragedy of flight PA9035 and the lives of those on board. But the book is about more than one deadly incident: it’s a story of the intricate ways Americans were shaping—and shaped by—World War II, even before the United States officially entered the conflict.

“Since around the 1980s, Americans have really whittled down their depictions of World War II to focus overwhelmingly on combat soldiers storming beaches or Churchill, Stalin, and Roosevelt—the high diplomacy,” says Blower, a BU College of Arts & Sciences associate professor of history and recipient of the University’s 2018 Metcalf Cup & Prize. “This is an attempt to help readers see the war in a new way, to remind them of the geographical, temporal, and political scope of the engagements Americans were involved with.

“It’s a Casablanca World War II story rather than a Saving Private Ryan story.”

Curious, Globally Engaged Americans

Flying to Europe today is a breeze. This summer, more than 112,000 flights were scheduled to zip passengers across the Atlantic from the United States. A single flight from New York to Lisbon—the final destination of the doomed Yankee Clipper—costs about $350 and takes less than seven hours, without any stops. That same trip on a Boeing 314 back in 1943 meant layovers in Bermuda and the Azores—the total flight time was about 27 hours—and would have set passengers back the modern-day equivalent of thousands of dollars.

With war raging across the globe, it took serious cash or influence to land a seat on the plane. To get on a transatlantic flight 80 years ago, you had to be somebody.

Like Major George Alfred Spiegelberg, a lawyer and member of General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s staff; or Manuel Diaz Riestra, a Spanish-born immigrant and self-made shipping magnate; or Benjamin Franklin Robertson, Jr., author and New York Herald Tribune reporter. In Americans in a World at War, Blower picks six globally connected passengers—including Spiegelberg, Diaz, and Robertson, plus pilot Sullivan—to focus on. The book charts their lives from the start of the Great War in 1914 on, weaving their personal histories into the world’s slide from one conflagration to another. Blower divides her narrative into four parts—World War I and its aftermath, two decades of relative peace, the start of World War II, and the year before the crash—breaking each with a short interlude to plot the Yankee Clipper’s fateful journey. Along the way, she busts a bunch of sepia-tinged myths, starting with America’s pre–Pearl Harbor isolationism.

“There’s an assumption in many popular narratives that Americans were minding their own business, that they were the war’s reluctant heroes. But the problem with that perspective is that it suggests Americans were not in the world in really dramatic and complex ways before World War II,” says Blower, who is also the author of Becoming Americans in Paris: Transatlantic Politics and Culture between the World Wars (Oxford University Press, 2011). “Americans were abroad, they were curious. Before the US became a superpower, they had to learn languages, they had to collaborate and compromise with other people. When they emerged from the war triumphant, they became, in many ways, more insular, less curious, less engaged; Americans lost a certain way of being in the world.”

By the time the plane is arcing over Lisbon, the stories of how Blower’s seven chosen subjects came to be on board, and the journey the world had taken to put them there, have been painted in technicolor detail.

“In order to fully understand these people’s motivations and the worldviews they were bringing to the war, you need to know where they’ve been,” says Blower. “And you need to know that World War II is a follow-on to all these earlier conflicts: the Bolshevik Revolution, the Spanish Civil War, tensions in the world’s colonies, the aftermath of World War I. You can’t really understand World War II if you don’t understand those things.”

A Broadway Star

Perhaps surprisingly, one of the most famous survivors of the crash—part of the seven-strong USO troupe on board—isn’t a star of Blower’s book. In the 1950s, singer and actress Jane Froman hosted an eponymous show on CBS and was played by Susan Hayward in the hit movie about her life, With a Song in My Heart. Instead, Blower turns to another USO singer, Tamara Drasin Swann—who preferred simply Tamara. A Ukrainian émigré, Tamara had fled civil war and revolution, hidden her Jewish ancestry, and made herself into a dazzling Broadway personality. Settled in Manhattan, she was the first to sing “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” decades before the Platters took it to number one in the charts.

“The most interesting chapter of Froman’s life is post–plane crash—it’s her recovery,” says Blower. “With Tamara, I had the same story about show business and the USO, plus this escape from the Ukrainian civil war, passing for non-Jewish, her father’s leftist politics—all this other stuff going on that was way more revealing to me.”

But not picking the low-hanging fruit meant navigating more research obstacles: for many of her subjects, there were no existing tomes and histories (or movies) to turn to, no neatly maintained archives. Researching the US Army officers on board threw up another issue: their work was, and largely still is, classified.

“They were not supposed to be on these planes,” says Blower. “They flew disguised as civilians, because they were flying through neutral territories on commercial airplanes.”

Some post-crash gravestone applications by family members provided tantalizing tidbits about the incognito officers. But Blower isn’t convinced that even their parents and spouses knew what they were really up to. The only Army officer she was able to get a solid handle on was Spiegelberg. Blower was able to track down his World War I records—and his daughter.

“She gave me access to scrapbooks that showed what he was involved in, so then I could go track down related government records,” she says. From the scraps of paper Spiegelberg’s family had preserved—which included his military orders—and his public Congressional testimony, she could follow the trail of his work helping to procure equipment and supplies for the US Armed Forces. Spiegelberg’s eventual destination when he boarded the Yankee Clipper was to be London, where he’d spent the past year negotiating the intricacies of Reverse Lend-Lease, part of a deal to share matériel and funding between Allied nations.

Capturing the Peril of War

Contacting the families of victims and survivors was something new for Blower. Typically, her approach to uncovering the past is to dig through archives for official documents and testimonies. But going out of her comfort zone helped unearth enough gems that she plans to incorporate it into future research. Her favorite find was a trunk full of records kept by relatives of Olympic athlete turned globetrotting businessman turned radio war correspondent, Frank Joseph Cuhel.

Blower says it was clear Cuhel had been planning a memoir of his life, from his time traveling and negotiating deals in Southeast Asia, through his narrow escape from the Japanese at the outset of the Pacific War, to serving as a war correspondent. The trunk even had rare—and highly delicate and flammable—acetate 16mm film he’d taken during his travels, which experts at BU’s Geddes Language Center helped transfer digitally.

“It’s pretty remarkable. I don’t know that I’ve seen this kind of footage of Americans in colonial Southeast Asia before; you could almost write a whole essay about this film,” says Blower. “It ranges from Manila to the mountains in Iran. It’s just little short snippets of him, and sometimes him engaging with customers or other travelers.”

Despite seemingly doing its bit for the war effort—ferrying secrets, as well as military experts, journalists, and entertainers—the Yankee Clipper’s passenger manifest wasn’t full of straight-arrow American patriots. And Blower says she tried to be fair in conveying the worldviews of all her subjects, even those who supported the Axis powers. Like shipping agent Diaz, who was seemingly doing everything he could to—sometimes literally—fuel an Allied defeat. The US government had long suspected Diaz of using his shipping line to support fascism, with many accusing him of helping funnel secrets and equipment to Axis agents, even providing oil for U-Boats. Blower writes that as children, Spaniards like Diaz were “raised to distrust the United States as a historic rival”; as an adult, he supported Spanish Civil War general turned Nazi-sympathizing dictator Francisco Franco.

“I tried to understand why somebody would feel that way, why they would have that perspective,” says Blower. “But I don’t do speculation, I don’t put words in their mouths. The story I tell is based solely on what could be found in historical records.”

Taking such a personal approach to the war also allowed Blower to tackle another assumption she says has been perpetuated in popular culture: that an Allied victory was always inevitable. In February 1943, it was far from a guaranteed result. Despite arduous Allied victories at Guadalcanal and Stalingrad, it was a time of immense peril. And the passengers on the Yankee Clipper knew it.

“The war is so complex and goes on for so long. And I’m hoping the book shows just how on their heels the Allies were until 1943,” says Blower. “That’s one of the interesting things about narrating it through individual lives: you can see people experiencing it forward in time rather than looking back retrospectively and anticipating what is going to happen. You can feel the contingency of the situations people find themselves in.”

But for the majority of the Yankee Clipper’s passengers and crew—including many of those Blower profiles—there were to be no more situations, no more forward in time. This was the end: sitting aboard a 106-foot-long marvel of modern engineering, perhaps chatting with one of their fascinating fellow passengers, and watching the darkening Tagus River edge ever closer.

This research was supported by a BU Peter Paul Career Development Professorship, the BU Center for the Humanities, an ACLS Frederick Burkhardt Residential Fellowship, a National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholars Fellowship, and the American Philosophical Society.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.