BU Alums Explore Dangers Journalists Face in New LA Times Documentary

BU Alums Explore Dangers Journalists Face in New LA Times Documentary

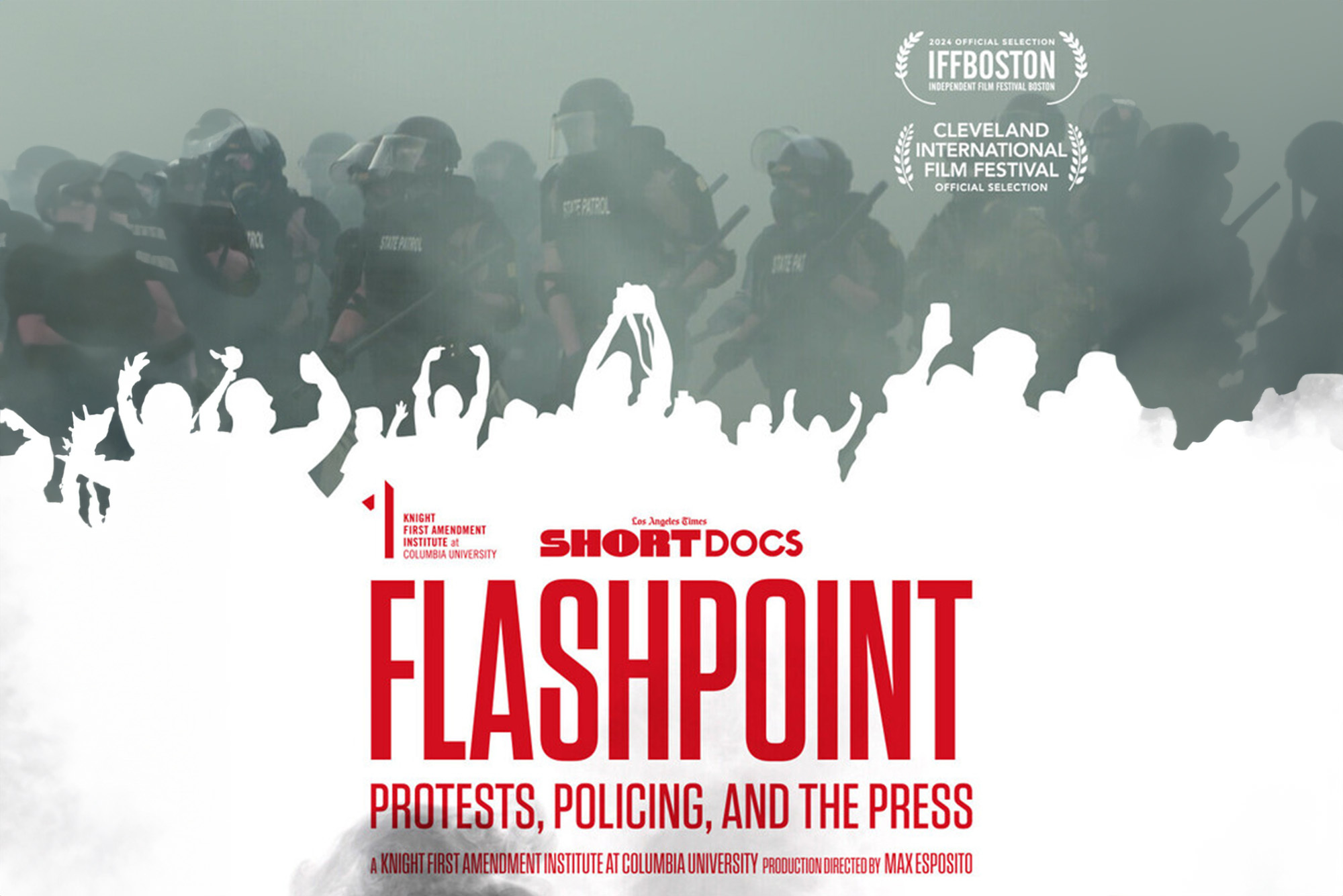

Flashpoint: Protests, Policing, and the Press follows reporters covering protests, such as the Black Lives Matter movement

In 2020, more than 400 journalists were attacked in the United States. And 80 percent of those attacks were allegedly at the hands of the police. The new LA Times short documentary Flashpoint: Protests, Policing, and the Press shines a light on the dangers journalists face at the hands of police when covering protests, despite the protections offered by the First Amendment.

The 25-minute film, which premiered on May 2—World Freedom of the Press Day—was directed by Max Esposito (COM’10) and edited by P. Nick Curran (COM’08), who met while they were studying journalism at BU’s College of Communication.

The documentary builds on a groundbreaking report from the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University by Joel Simon titled Covering Democracy: Protests, Police, and the Press. Simon is a former Knight Institute Fellow and founding director of the Journalism Protection Initiative at the CUNY Craig Newmark School of Journalism.

Using raw footage from protests as well as interviews with practicing journalists and lawyers, Esposito and Curran hope their documentary will spark a broader conversation about the treatment of journalists—specifically journalists of color—when documenting pivotal moments of civil unrest.

After graduating from COM, Esposito and Curran shared a production studio in Allston with a handful of film friends, a space teeming with creative energy, Esposito says. He and Curran were working independently, but often bounced ideas off each other and reviewed each other’s edits.

Nearly 16 years later, the longtime friends would reunite in New York and collaborate on the Flashpoint project. The documentary premiered as part of the LA Times Short Docs series, winning the Audience Award for Best Documentary Short at the Independent Film Festival Boston in early May.

Bostonia spoke with Esposito and Curran about the documentary-making process, the ever-changing identity of modern journalists, and Flashpoint’s relevance in today’s social climate.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Q&A

with Max Esposito and Nick Curran

Bostonia: What inspired you to explore this topic and make this film?

Max Esposito: The way this film came about is a little different than how a lot of documentaries come to be, where often the filmmaker, the film team, has an idea of something they’re interested in, and then they pursue it. This was technically commissioned by the Knight First Amendment Institute, part of Columbia University. They put out an RFP [request for proposal] and were looking for filmmakers interested in telling this particular story because they’re also sponsoring a report by Joel Simon. His report looked at how journalists cover protests in the United States and how their rights are infringed upon by police when they cover them. He looked at 2020, at Ferguson [riots, in Missouri], and at Occupy Wall Street. He looked all the way back to the Civil Rights movement and saw that this trend isn’t anything new and is happening consistently throughout US history. So the film tries to explore that, but in a much briefer, 25-minute window.

Bostonia: How did your partnership with the LA Times come about?

Esposito: We finished the film in 2023 and were looking for an outlet. It was spearheaded by the Knight First Amendment Institute, which wanted a platform for the film. We talked to the New York Times Op Docs and the New Yorker’s short documentary series, and for various reasons, it landed in the LA Times Short Doc series.

P. Nick Curran: I hadn’t seen much coverage that analyzed how that [2020] Black Lives Matter summer happened in LA, and since this was by design a sort of LA-centric film with a lot of the characters, the LA Times was interested in acquiring it.

Bostonia: What was the process behind collecting footage for the documentary? And how did you identify the journalists featured?

Curran: There was the whole archival research component, which was our producer, Daisy Schmitt, doing a deep dive across Twitter and Instagram and into various archives. I covered protests in general. Four years ago in Fort Greene in South Brooklyn, [protestors] lit a police van on fire. And that was the beginning of it all. So a lot of the New York footage was mined from that summer, and then moving out from that, friends and colleagues who were also out filming.

One of the more surreal parts of this film was when Max first brought me in early on, getting Joel’s report, reading through it, and thinking, oh, I was at all of these things that are in this archive of historical documents. It was a very bizarre experience to read through.

Bostonia: Did you ever find yourself in danger in those situations?

Curran: Yeah. I mean, that’s unfortunate, it happens all too often. It’s only gotten worse since 2020 as far as specifically police response to protests. In Minneapolis, for example, you had journalists Mike Shum and Katie Nelson in the film, who were shot at frequently with nonlethals. As someone who has been shot with nonlethals, they are anything but. One, people have died, and two, you have journalists like Linda Tirado, who lost her eye. I remember in early 2021 in Minneapolis, seeing a journalist have his hand broken by a nonlethal.

Bostonia: College campuses worldwide are experiencing protests about the Israel-Hamas War and many are covered by student journalists. How is Flashpoint particularly relevant, given the current situation on college campuses?

Esposito: There are a few thoughts there. The closing line of the film, spoken by Joel Simon, says something to the extent of, ‘This will continue to happen.’ Anytime there is civil unrest, anytime there are protests, we’re going to see this issue again, because it’s unresolved. We finished the first iteration of the film in 2023. Then we finished the LA Times version before the protests on college campuses. When we screened the film at the Independent Film Festival Boston [coinciding with the film’s premiere on May 2], it was that weekend that we really saw a significant shift in the amount of protests happening on college campuses in the US. There was this surreal energy about the film coming out at this moment—we saw the subject matter of the film play out in real time, which unfortunately goes to show how relevant and important the film’s story is, because this issue is recurring—it’s unresolved.

It’s hard to put into words what it was like seeing what was happening on college campuses. You’ve got journalists that are at the very inception, the very beginning of their careers, and they’re being attacked by police. Day one. It goes to show how crucially relevant the story is and hopefully, more people who see it can start to change the conversation about how we treat journalists, whether it’s a college student or a seasoned veteran.

Bostonia: Flashpoint speaks to the role of journalists and how it’s shifted. What is the future of journalism? Can anyone be a journalist?

Esposito: I think a lot of people are wondering that, but maybe a different way to think about it is less, where is the institution going? but instead, looking at college students that are up-and-coming journalists. And I say that because I studied journalism at BU, and I remember when I graduated in 2010, a few years after the financial crisis, newsrooms were shrinking. Journalism institutions couldn’t figure out how to monetize their digital publications. There was this fear in the air about where journalism was going, this undercurrent of uncertainty, which I think is there in a different way now. Even though everyone’s scared, I think that young people and my peers are still so passionate about telling stories.

What we saw during the protests brought that to light: student journalists rose to the occasion and did reporting that a lot of mainstream news outlets weren’t able to do. They had access and they told amazing stories. They captured amazing photos. I don’t know where journalism is going to go, but I feel really confident in the [younger generation’s] passion for it. I don’t have the answers, but someone’s going to figure out what the next evolution of journalism looks like.

Bostonia: How have audiences reacted to Flashpoint thus far?

Esposito: Positive. We got the Audience Award for Best Documentary Short at the Independent Film Festival Boston, which was really exciting.

Curran: I’ve had colleagues and friends watch it, and they’ve had a good reaction. But I’ve also had more radical street organizers [watch it] who I thought wouldn’t have enjoyed something told from this perspective, and one in particular was like, ‘This is really great. It really examined the issue in a really interesting way.’ It has a broader appeal.

Bostonia: What’s next for you both? Are there any projects on the horizon?

Esposito: There is an interest, a twinkle in the eye, of whether this story could be expanded into something longer because there’s so much information that did not make the film. It could be a series. Still within the context of protests, there’s so much more information there. And if you zoom out and look at the state of journalism in general, there’s so much there to explore. So there’s a part of me that’s intrigued in looking at that further, but there hasn’t been any action on that so far.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.