Can Civilians Own Automatic Weapons? Supreme Court Takes Up the Issue of Bump Stocks

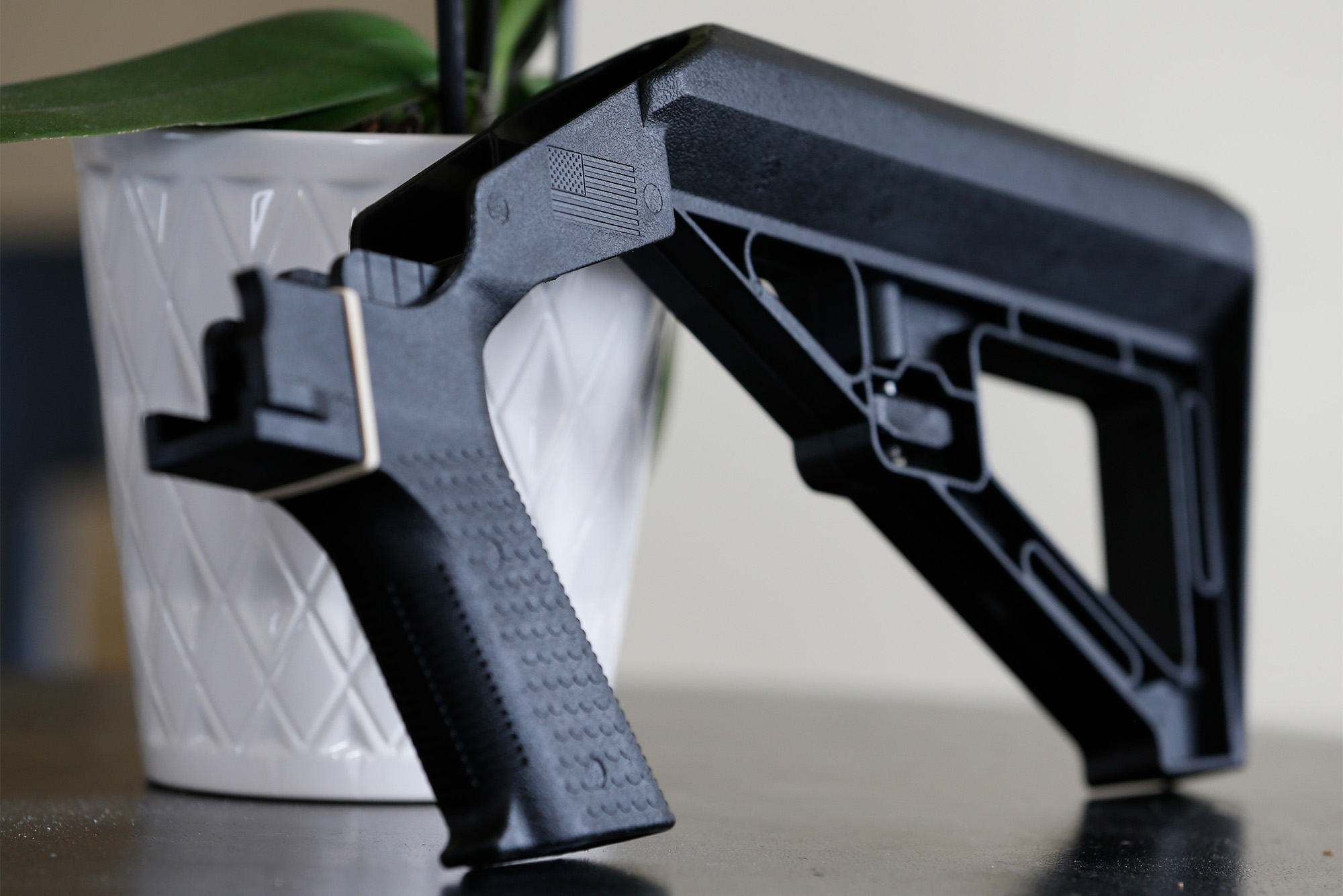

Justices will hear arguments in Garland v. Cargill on Wednesday, a case that will determine whether bump stocks—devices that can be added to the back of semiautomatic weapons that harness the gun’s recoil to repeatedly fire the weapon—are illegal under a law that bans “machineguns.” Photo via AP/Steve Helber

Can Civilians Own Automatic Weapons? Supreme Court Takes Up the Issue of Bump Stocks

Any decision the justices make will likely be seen as signaling “more or less skepticism toward gun control,” says BU LAW’s Cody Jacobs

On Wednesday, the United States Supreme Court will hear arguments in a case that will determine whether civilians can own guns outfitted to make them indistinguishable from automatic weapons.

At the heart of the case, Garland v. Cargill, are bump stocks, devices that can be added to the back of semiautomatic weapons that harness the gun’s recoil to repeatedly fire the weapon. The justices will have to decide whether these devices turn a weapon into a “machinegun,” which are illegal under a 1986 law. The suit was filed by Michael Cargill, an Army veteran and firearms instructor who turned in his bump stocks. Now, he’s challenging the federal government (under US Attorney General Merrick Garland) over regulations that define bump stocks as “machineguns.”

Here, it’s important to understand what distinguishes a semiautomatic weapon from an automatic one. In a semiautomatic weapon, a bullet automatically slides into a loaded position immediately following each shot—but it requires the person using the weapon to pull the trigger to fire each time. Holding down the trigger in a semiautomatic weapon will still only fire one bullet. An automatic weapon, by contrast, will fire a continuous stream of bullets (as many as nine bullets per second), usually as long as the person using the weapon holds down the trigger.

A bump stock replaces a rifle’s standard stock, or the part of the gun that rests on the user’s shoulder. Unlike a standard stock, a bump stock allows the rifle to slide back and forth, harnessing the gun’s kickback to “bump” the user’s finger against the trigger. It allows the rifle to fire again and again, even as the shooter keeps the finger still.

The Trump administration made bump stocks illegal in 2018, after a gunman opened fire at a music festival in Las Vegas, killing 60 people and wounding hundreds more. One reason the shooting was so deadly, experts determined, was because the lone shooter equipped the majority of his weapons with bump stocks. Administration officials determined that bump stocks violate the 1986 law that makes it a crime to own a “machinegun.” But, that law is ambiguous, and federal courts are divided about whether bump stocks do, in fact, meet that definition. This is where the Supreme Court picks up the case.

BU Today spoke with Cody Jacobs, a Boston University School of Law lecturer, whose research focuses on firearm policy and the Second Amendment, about Wednesday’s case, and what it could mean.

Q&A

With Cody Jacobs

BU Today: What’s at stake in this case? Although it seems to be a simple question of machinery, are there bigger questions or issues the justices must consider?

Well, the bump stocks themselves are pretty important. Outside of any implications for other cases, this case will decide whether bump stocks remain legal at the federal level—bump stocks allow commonly available semiautomatic weapons to fire at a rate that is similar to automatic weapons. This can make mass shootings much more deadly, such as the Las Vegas shooting which prompted the regulation at issue in this case in the first place.

The bigger issues in this case from a purely legal perspective are ones of statutory interpretation. The case asks what “machinegun” means under the federal laws that heavily restrict the use of such guns by civilians. This could have implications for other kinds of firearms and accessories that seek to make it easier to fire multiple rounds from a gun without having to press the trigger down separately each time.

Of course, beyond the purely legal question, there’s the larger issue of the gun control debate as a whole, which this court placed a large shadow over last term with its decision in Bruen allowing virtually anyone nationwide to get a concealed carry permit. Any decision the justices make in this case will likely be looked at in that light—as signaling more or less skepticism towards gun control—even if the legal issues involved here are completely different (there’s no Second Amendment issue raised in this case).

BU Today: To what extent is this case tied to the pair of Chevron-related cases the court heard earlier this year? Those cases challenge a 1984 Supreme Court decision known as the Chevron doctrine—that courts should defer to an agency’s reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous law.

Theoretically, not at all. This case involves an interpretive rule from [the US Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, or ATF] about what a “machinegun” is. An interpretive rule basically just says, “this is how the agency is going to interpret the rule and try to enforce it,” but it’s not the same as a regulation, which has the force of law once it goes into effect. Regulations are subject to Chevron deference (for now), but interpretive rules aren’t. So, theoretically, the court will just look at this as a pure issue of statutory interpretation, without any consideration of what the agency’s interpretation is or has been.

That said, I think a Chevron-type issue is lurking in the background here. The ATF changed its position on bump stocks. Until 2018, the agency concluded that bump stocks were not “machineguns.” Then, in response to Las Vegas and at the direction of President Trump, the agency revised its interpretation. The challengers to the law highlight this heavily in their briefing as a reason that the interpretation is wrong and, I think, implicitly, that it’s politically motivated.

Again, this really shouldn’t have any legal bearing on the case, but it’s something to keep an eye on because the ability to interpret how the law applies to new situations, or changes interpretations in response to new events or information, is an important power of the executive branch. If it’s curbed by the court, it will give more power to Congress, which in practical terms will reinforce the status quo on a number of issues by preventing presidents from making changes through interpretative rule-making.

BU Today: Does the composition of this court make you think the ruling will go one way or the other?

In general, I would assume this court to be very skeptical of regulatory agencies, especially when it comes to guns. However, this case presents a particularly extreme argument, both in terms of the legal interpretation the challengers are advocating (that something isn’t a “machinegun” as long as the person using the weapon has to do something to make it keep firing) and with respect to the politics of the underlying issue (the ban on bump stocks is popular and was put into place by President Trump).

BU Today: What will you be listening for, and why, during Wednesday’s arguments?

If the court focuses a lot on interpreting the words of the statute, I think that’s good for the government. If the court focuses a lot on ATF’s rule-making process, that would be good for the challengers. I’d be specifically keeping an eye on Justice Gorsuch, who, despite being a regulatory skeptic, has been willing in the past to follow the plain text of a statute where it leads even when it goes against his (assumed) ideological priors. Of course, the Chief Justice [John Roberts] and Justice Kavanaugh are always key votes since they are often seen as ideologically in the middle of this court (though they are still very far to the right ideologically in a general sense).

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.