15 Black BU Alums Who Have Left Their Mark

15 Black Boston University Alums Who Have Left Their Mark

In the worlds of politics, civil rights, sports, the arts, media, medicine, education, to just name a few, these prominent BU alumni, both living and deceased, are worth celebrating

To celebrate Black History Month, Bostonia combed its archives for Black Boston University alumni, both past and present, who have left their mark across society in some way. It’s no secret that Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59) is a notable BU alum, which is why we he’s not included on this list. (And no, we did not overlook Howard Thurman [Hon.’67], dean of Marsh Chapel from 1953 to 1965. Thurman was not a BU alum, but rather an honorary degree recipient.) Herewith our list, in no particular order, of BU alums worth honoring during Black History Month.

Barbara Jordan (LAW’59, Hon.’69), 1936-1996

Barbara Jordan broke a glass ceiling, plain and simple. More than one, actually. Angela Onwuachi-Willig, BU School of Law dean, says this about Jordan: “She was the first African American woman elected to Congress from the South, and she was a really outspoken advocate for justice. She was one of the names my mother always invoked around the house as someone I should look up to, to see all the possibilities I had here in the United States.” Jordan was not only the first African American woman to represent Texas in Congress, she was a member of the House Judiciary Committee, and she gained national notoriety after a fiery speech to the committee in 1974 supporting the impeachment of President Richard Nixon. Two years later she was the first African American, and first woman, to deliver a keynote address at a Democratic National Convention.

Rebecca Lee Crumpler (MED 1864), 1831-1895

The first Black woman to graduate from a US medical school, Rebecca Lee Crumpler was the definition of the word trailblazer. Born in Delaware, she moved to Charlestown, Mass., in 1852, and shortly after the Civil War she went to Virginia to help former slaves who had been refused medical treatment by white doctors. Her legacy continued when she published a medical book (one of the first Black physicians to publish a book) that had clear messaging about women’s health, a rare guide at the time. Crumpler’s strong Boston ties intensified when she worked as a nurse in Charlestown before enrolling in the historic New England Female Medical College, which later merged with Boston University. Melody McCloud (CAS’77, MED’81), founder and medical director of Atlanta Women’s Health Care, has spent years researching and promoting Crumpler’s legacy. And although Crumpler’s house is a stop on the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail, it took more than 125 years after her death for a headstone to be erected on her previously unmarked grave in Hyde Park, thanks to the efforts of another BU alum, Vicky Gall (Sargent’73, Wheelock’83), president of the Friends of the Hyde Park Branch Library.

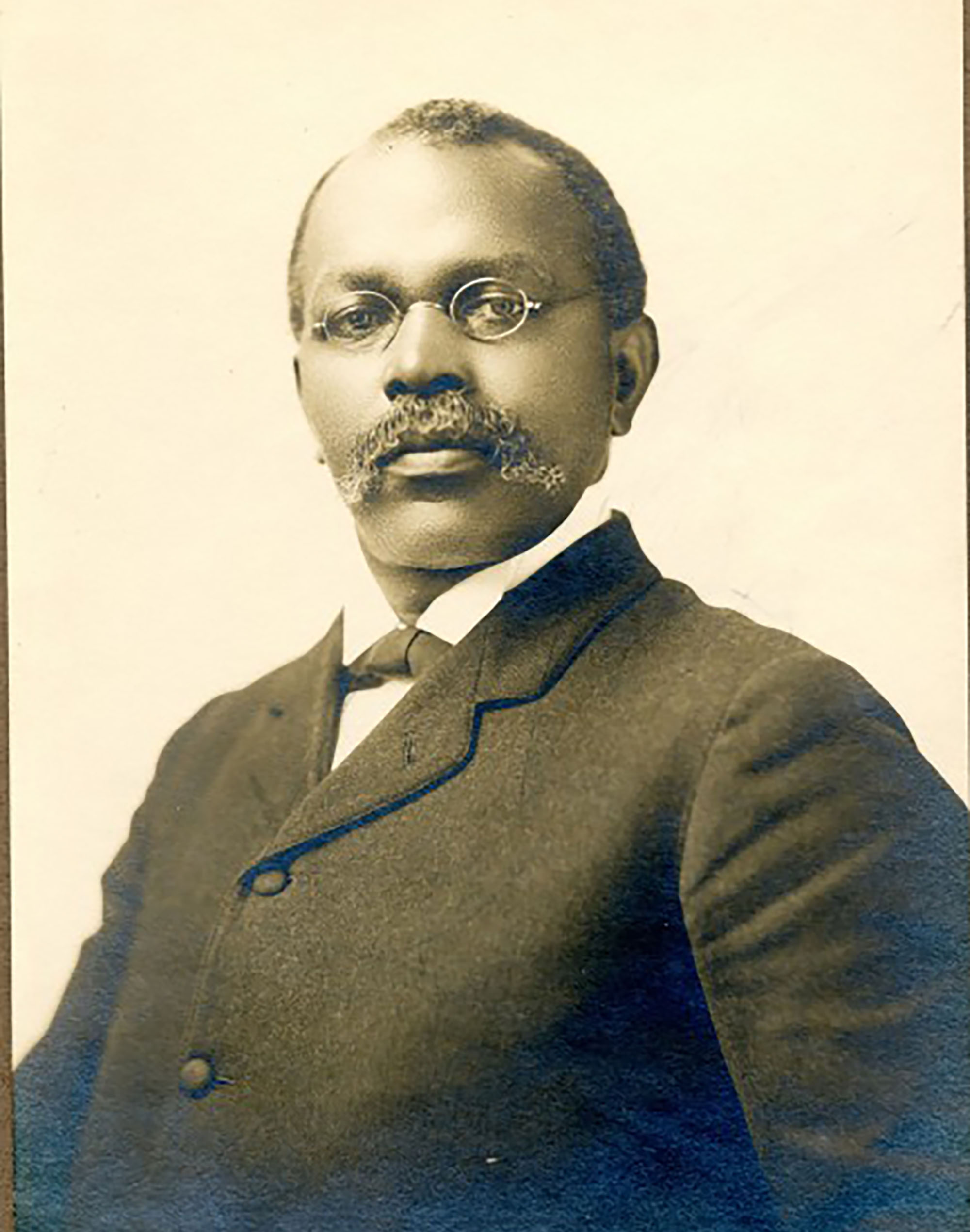

Solomon Carter Fuller (MED 1897), 1872-1953

Perhaps one of the lesser known, yet most impactful, BU alums, Solomon Carter Fuller was the first Black psychiatrist in the United States. After completing an internship at Westborough Insane Hospital, later Westborough State Hospital, he became a pathologist and joined the BU School of Medicine faculty. A few years later, he joined four other research assistants at the Royal Psychiatric Hospital in Munich, Germany, to work under Alois Alzheimer. As the Washington Post reported in a 2021 feature on Fuller: “As a pathologist, Fuller performed numerous autopsies, which enabled him to make observations—none of them more pivotal than the neurofibrillary tangles and miliary plaques he encountered while examining the brain tissue of deceased people who had had dementia. Fuller reported on the significance of neurofibrillary tangles five months before Alzheimer did, and his discovery identified a physically observable basis for this affliction, which so decimated the memories of its victims. Ultimately, the results of Fuller’s research helped to confirm that the condition known as Alzheimer’s was not the result of insanity but rather a physical disease of the brain. He also went on to publish the first comprehensive review of this disease.” Over time Fuller’s white colleagues were paid more and promoted over him, ultimately driving him to retire from BU. Late in his life, Black Psychiatrists of America established the Solomon Carter Fuller Program for aspiring Black psychiatrists, and today the American Psychiatric Association honors one person for pioneering work to better the lives of Black people with its annual Solomon Carter Fuller Award. The Medical Campus Solomon Carter Fuller Mental Health Center was named in his honor.

Mike Grier (CAS’97), b. 1975

As a six-foot-one, 225-pound forward, Mike Grier won a national championship with Boston University’s men’s hockey team—and he didn’t stop there. He went on to a successful 14-year career in the National Hockey League. And he didn’t stop there, either. He’s now the general manager of the NHL’s San Jose Sharks, making history as the first Black general manager in the NHL. “I always put pressure on myself to do the job right, to be successful, not too dissimilar from as a player,” Grier told Bostonia. “Hopefully, I’ll be able to open the door for Black people behind me so owners and others can see that they can do the job.”

Elma Lewis (Wheelock’44), 1921-2004

Born in 1921 in Roxbury, Mass., Elma Lewis was not yet 30 years old when she began changing young lives. Her journey started in 1943, when, using money she earned by acting in local theater, she graduated from Emerson College. A year later, she earned a master’s in education at BU. And in 1950, just 29 years old and driven by her own childhood experiences, Lewis opened the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts in Roxbury to help promote arts and communication education for Boston’s Black youth. She went on to become a bright light in the city across the arts, education, and civil rights. In 1981, she became one of the first women to receive a MacArthur Foundation “Genius Grant.”

Edward Brooke (LAW’48,’50, Hon.’68), 1921-2003

After editing the BU School of Law Law Review in the late 1940s, Edward Brooke ran his own practice in Roxbury until 1962, when he was elected Massachusetts attorney general—the first Black attorney general in the country. “My God, that’s the biggest news in the country,” none other than President John F. Kennedy (Hon.’55) said at the time. But Brooke was not done breaking barriers. In 1966, on the heels of gaining public attention for his aggressive pursuit of the Boston Strangler and repeated prosecutions of corrupt politicians, Brooke became the first popularly elected African American US senator. He went on to serve two terms, and was always an outspoken advocate of free speech. “Dissent and protest are essential ingredients in the democratic concoction,” he once said. “Without them an open society becomes a contradiction in terms, and representative government becomes as stagnant as despotism.

Emanuel Hewlett (LAW’1877), 1850-1929

Emanuel Hewlett, or E. M. Hewlett, broke a lot of big ground, and he was following some big shoes. He was the son of the first African American instructor at Harvard University, Aaron M. Hewlett. He became the first Black person to graduate from the Boston University School of Law and he went to enjoy a thriving Washington, D.C., legal practice. He then became a respected judge and civil rights activist. And here is some fascinating trivia: his sister Virginia was married to Frederick Douglass, Jr., the son of 19th-century social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman Frederick Douglass. Hewlett argued a number of important cases before the United States Supreme Court, and he fought bars and restaurants in Washington that were refusing to serve Black customers or ignoring or overcharging them.

Ida Lewis (CGS’54, COM’56), b. 1934

The field of journalism has always struggled with hiring and promoting people of color. It’s not known as a diverse profession, so when Ida Lewis rose from the Paris correspondent for several publications in the 1960s, including Life and the New York Times, to the first editor-in-chief of Essence magazine in 1971, it was a big deal. Shortly afterward she founded Encore, a newsmagazine exploring African American perspectives on global issues, becoming the first Black woman to publish a national magazine. And that was even bigger. (She later took over as editor of Crisis, the NAACP magazine.) “The world is getting smaller, and we’re all in it together,” she told BU Today in 2005. “I think it’s important that all students cultivate an open mind. If you’re going to report, you have to keep your pulse on human beings.”

Grace Bumbry (CFA’55), b. 1937

In the arts, awards don’t get much bigger than the Kennedy Center Honors. In 2009, internationally celebrated mezzo soprano Grace Bumbry was among those honored by the Kennedy Center. Her voice, sultry and wide-ranging, may have defined her on stage, but off stage she was equally influential as a world-leading vocal teacher who created the Black Musical Heritage Ensemble. Bumbry broke a color barrier at the Bayreuth Festival in Germany in 1961, when the grandson of Richard Wagner cast her as Venus in a performance of the opera Tannhäuser, and she received 42 curtain calls. Just 24, she was the first Black singer at the festival, and it caught the attention of Jackie Kennedy, who later invited her to sing at the White House. “It was an enormous success, and a wonderful feeling that my efforts were not in vain,” Bumbry said of her Bayreuth performance.

Enoch Woodhouse (LAW’55), b. 1927

One of the last surviving members of the Tuskegee Airmen, America’s first all-Black World War II combat flying unit, Enoch Woodhouse told Bostonia in 2021: “Blacks were told, and it was publicized, that they lacked intelligence. We were thought to be skilled for and were utilized only in support positions. That means truck drivers, laundry people, oil fillers for airplanes. Even though we were trained in basic training, when we got into the army, we were all relegated to service functions.” The Tuskegee Airmen changed that forever, as they were instrumental in integrating the US Armed Forces, and it helped earn Woodhouse and others the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest honor bestowed by the US Congress on individuals or institutions for distinguished achievements and contributions. President George W. Bush presented Woodhouse his medal in 2006, calling it “a gesture to help atone for all the unreturned salutes and unforgivable indignities.”

Uzo Aduba (CFA’05), b. 1981

There is no other way to say it: she created one of the most riveting, dramatic, searing roles on television in the last 20 years. Uzo Aduba’s character on the smash Netflix comedy and dramatic series Orange Is the New Black, was named Suzanne Warren. But anyone who watched the show knew her by her nickname: “Crazy Eyes.” And it led to other hit shows, including playing a therapist in the remake of In Treatment and starring now in the Shonda Rhimes Netflix drama The Residence. But her role on OITNB remains career-defining for her. Here is how Bostonia described her portrayal there: “OITNB inmates and guards alike struggle to maintain their humanity in the confines of the fictional Litchfield federal minimum security prison. Although modesty and professionalism would prevent Aduba from agreeing, Crazy Eyes upstages them all. She is a complex, nuanced creation—an innocent with a quick, well-versed mind, a child’s frail psyche, and a simmering lethal violent streak.” Aduba knew the role was the perfect fit for her. “When I met Suzanne, it just felt right,” she said. During her time at BU, she was one of the University’s all-time top sprinters. She excelled in the 55-meter, 100-meter, and 200-meter races and won the BU Athletics Aldo “Buff” Donelli Leadership Award, given to a senior for “outstanding leadership on and off the field.”

Richard Taylor (COM’71), b. 1949

What do student-athletes look like? They look like Richard Taylor, who was a captain of the BU men’s basketball team his senior year and also the University’s first Rhodes Scholar. Never a star player, he was always a valuable reserve. His coaches said his statistics didn’t define him; instead, his energy, on-court leadership, and defensive tenacity made him invaluable. Off the court, though, is where he has shined through the years. He did significant research on MLK. After receiving a bachelor’s degree in journalism at BU, he went on to earn a bachelor’s in philosophy, politics, and economics at Oxford, then a master’s in business administration and a JD from Harvard. His education and leadership earned him spots on the BU Board of Trustees, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston board of directors, and the Boston branch of the NAACP. And he served as Massachusetts secretary of transportation under Governor Bill Weld, overseeing a number of landmark construction projects, including rail service from Worcester to Boston and the Ted Williams Tunnel.

Ruth Batson (Wheelock’76), 1921-2003

Long before the famous Boston busing crisis of the 1970s, Ruth Batson stood up before the Boston School Committee in the early 1960s and challenged it to do better on segregation, arguing that there was a direct link between schools with poorer facilities and those with high Black enrollment. Batson was never one to hold her tongue, becoming chair of the New England Regional Conference of the NAACP, and eventually the first Black woman on the Democratic National Committee and the first woman elected president of the NAACP’s New England Regional Conference. She also held numerous roles at BU, including director of the School Desegregation Research Project and as an associate professor in the School of Medicine’s division of psychiatry.

John Wesley Edward Bowen (PhD, 1887), 1855-1933

He was born into American slavery, which is why it’s almost impossible to overstate the significance of the achievement by John Wesley Edward Bowen. When he was three years old, his father purchased the freedom of his wife and their son. After earning his degree from New Orleans University, Bowen went on to earn a PhD in theology at Boston University, with extra work in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, German, and Arabic. Born in 1855, he was the first African-American born a slave to earn a PhD in the United States. After graduating, he continued to break new ground, moving to Atlanta, where he became the first Black professor at Gammon Theological Seminary. He and his wife, Ariel Serena Hedges (Bowen), herself a professor of music at Clark College in Atlanta, had four children. Bowen’s essay, “An Apology for the Higher Education of the Negro” (Methodist Review, 1897), spoke passionately about higher education and classical studies. He died in 1933 at the age of 78.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr (LAW’98, COM’98)

She has become, over more than two decades of reporting and legal analysis, one of the most prominent and visible Black journalists in America, thanks in large part to her combined education background in both law and media at BU. In fact, Kimberly Atkins Stohr acknowledges that she chose the BU School of Law because it offered a rare dual JD/MS with the College of Communication. Once in law school, she shone, winning best oralist in the Homer Albers Prize Moot Court Competition before a panel of judges, a panel that included then–US Supreme Court Justice David Souter. After starting her career at a small litigation firm, she moved to New York, took the state bar exam and at the same time applying to Columbia Journalism School. Her Columbia acceptance letter arrived before she was admitted to the bar. “I took that as a sign,” she said of that moment in her career. “I went there and never looked back.” She grew as a journalist at both the Boston Globe and the Boston Herald, covering politics, policy, and the Supreme Court, while also gaining broadcast experience as a frequent guest commentator on C-SPAN and MSCNBC, where her background in legal matters was valuable. She was the first Washington, D.C.-based news correspondent for WBUR, and she has made regular appearances on NBC’s Meet the Press, as well as on CNN, Fox News, NBC News, PBS, NPR, Sky News (UK), and CBC News (Canada). Reflecting on her time at BU, and the pride she felt at winning the Moot Court Competition, Stohr wrote: “The silver award bowl I received as best oral advocate still sits on my shelf at home. The decades have brought some tarnish to the silver, but the memory still gleams.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.