Aphasia Robs Millions of Communication. Boston University Is Helping Them Regain Their Voice

Treatments, informed by research, make BU and Sargent College a leader in combating the neurological disorder

BU is a “leader in medicine’s efforts to…improve long-term outcomes for people” with aphasia, according to Maura Silverman, executive director of the nonprofit National Aphasia Association. Photo by mattjeacock/iStock

Aphasia Robs Millions of Communication. Boston University Is Helping Them Regain Their Voice

Treatments, informed by research, make BU and Sargent College a leader in combating the neurological disorder

Tiffaney Frongillo limps, slightly, to the front of the classroom in Boston University’s Sargent College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences. An invisible cane of courage assists her to the podium for a short speech in front of seven fellow people with aphasia. They’re here for a special Toastmasters program that eases participants into public speaking. It’s part of their therapy to reclaim their communication skills from the neurological disorder, which typically follows a stroke or head injury and damages the use or understanding of language, reading, and writing.

Aphasia afflicts two million Americans, and the Sargent attendees are at various stages of recovery. Frongillo speaks haltingly—with an occasional, soft ugh of frustration when she struggles with a word—during a short talk on football and her beloved New England Patriots. “I absolutely loved Tom Brady, my favorite player all-time,” she says. As for the recent roster: “Coach Mayo, not good,” she says of the just-fired Jerod Mayo. “He must have known it we–ugh–was coming.”

She explains why she’s come to this program for two years, calling it “my family.” Email is easier for her, and in an exchange after the meeting, she recounts running a learning center she founded for children with autism in Beverly, Mass., until five years ago, when a stroke made that work impossible. Today, she’s a stay-at-home mom for her 11- and 8-year-olds. “Aphasia causes frustration and stress,” she writes. “It can affect my whole family. But we are a strong team! My aphasia doesn’t affect my intelligence.”

There is no cure for aphasia. But at BU, a blend of clinical and research programs—led by Sargent’s Aphasia Resource Center (ARC) and the University-wide Center for Brain Recovery (CBR)—have vaulted the University to the vanguard of institutions working to make it a condition that can be lived with more easily. Thanks to BU researchers and clinicians, for example, we have the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination, a commonly used method for diagnosis, as well as an enhanced understanding of the role of neuroplasticity in aiding recovery—which involves leveraging the brain’s ability to use its functioning regions to newly process language and counter aphasia’s effects.

Maura Silverman, executive director of the nonprofit National Aphasia Association, says that Sargent’s approach of “connecting cutting-edge research with hands-on clinical interventions has resulted in a model for the larger aphasia community, and has positioned BU as a leader in medicine’s efforts to…improve long-term outcomes for people.” CBR, she says, “has played a vital role in advancing the field of aphasia research and treatment. Their commitment to the intersection of scientific discovery and clinical care has helped shape our field’s understanding of language habilitation and recovery, while directly improving the lives of individuals with aphasia and their families.”

Back at the Toastmasters event, Chris Carroll follows Frongillo at the podium. His recovery is further along; three and a half years at BU helped bring his speech back from three months of muteness following a stroke—“and I’m very grateful,” he says. He launches into a near-flawless talk about his Boston childhood and his favorite downtown pizza place, Regina Pizzeria. During Frongillo’s talk, the room’s screen featured snippets from her presentation; during Carroll’s, it displays visuals, including a watercolor of the restaurant. “My parents, matter of fact, they were dating when they ate at the same place,” he tells the room. “It’s been there forever.”

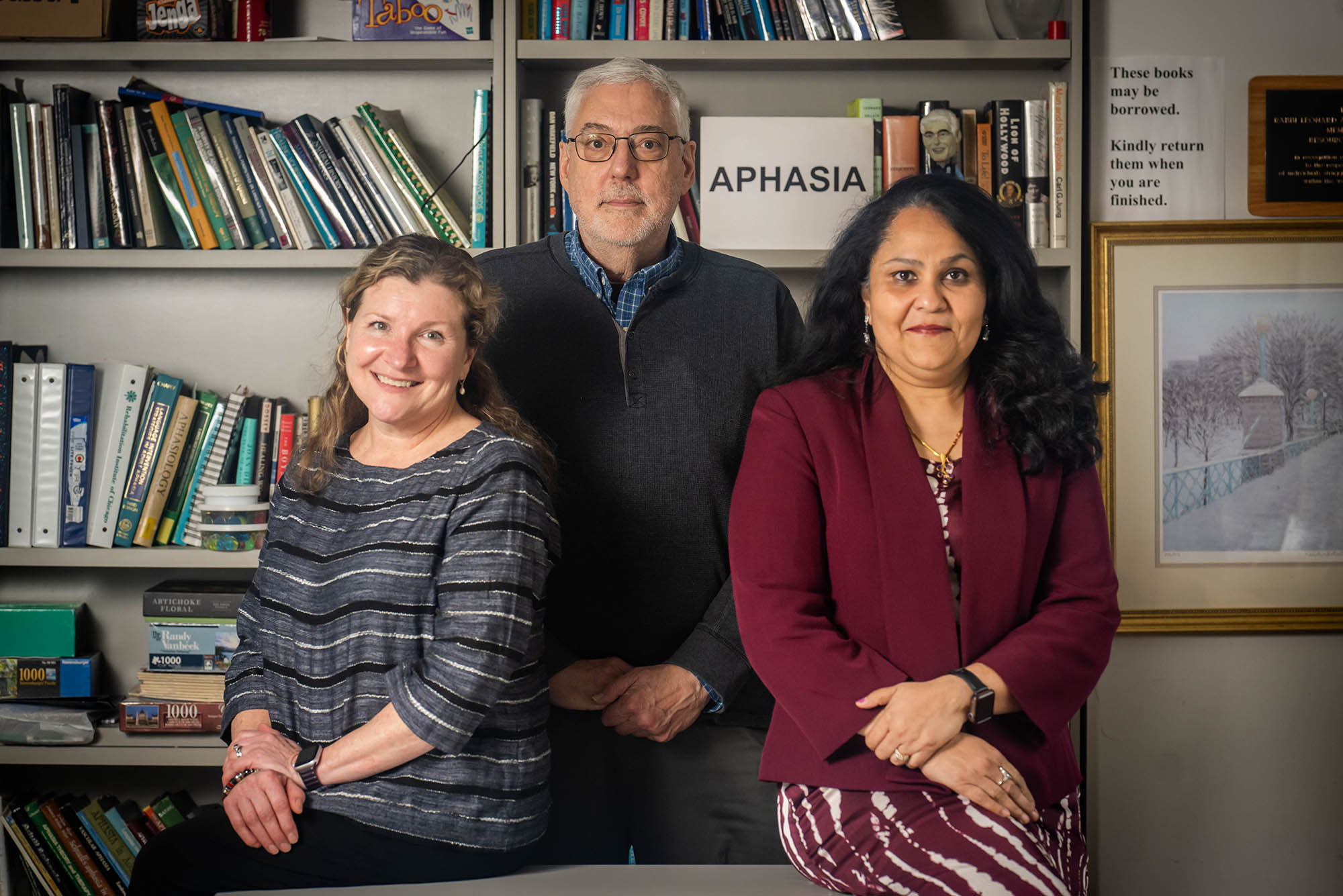

One by one, attendees give four-minute talks, each received with applause and words of encouragement, including from two student interns working the screen-controlling laptops—Jessica Lindenberg (Sargent’26) and Sarah Finnegan (Sargent’25,’26)—and faculty lead Jerry Kaplan, a Sargent lecturer and ARC’s clinical supervisor.

ARC offers this and an array of other community and group therapy programs, online or in person, for people with aphasia: listening to and discussing favorite songs, indulging in performing arts (members put on a show at the end of the semester), reading and discussing books, analyzing movie scenes, and sharing stories. Many of the center’s patients often participate in the University’s aphasia and brain recovery research and education, sparking a virtuous cycle, where their concerns and questions advance and inform new studies and train future clinicians—and, in turn, they benefit from breakthroughs in treatment and care they and others like them have helped pioneer.

Treating and Researching Aphasia—and Giving Hope

As the Toastmasters event demonstrates, people with aphasia can struggle to find words, finish sentences, or use the right words. Some have difficulty grasping written material or writing sentences that make sense. These symptoms can follow a stroke, which damages or destroys brain cells by either blocking or cutting blood flow—hence, oxygen and nutrients—to the cells or by causing a blood vessel to rupture and bleed. And aphasia isn’t just something that affects older adults. Kaplan has seen the condition increasingly strike much younger patients during his career. ARC recently produced a five-part documentary explaining the condition. “Johan, in our film, was 23,” Kaplan notes.

While most commonly caused by a stroke or brain hemorrhage, aphasia made headlines in recent years following two celebrity cases that resulted from different causes: former congresswoman Gabby Giffords, who was shot in the head by a would-be assassin, and actor Bruce Willis, who developed a dementia-related type.

Both cases brought fresh attention to BU’s aphasia programs, which also saw an uptick in interest after two of its patients appeared on the PBS NewsHour in 2022, clarifying the condition’s hurdles—and discussing how they live with it, successfully. One said her kids “know why my word is not perfect, but I understand, and they understand me.” Though BU also treats patients whose condition may be too severe for such public outreach, those who can communicate effectively can give others hope, “because all these folks have come a long way in their journey and are willing to share it,” says Elizabeth Hoover (CAMED’13), ARC clinical director and a Sargent clinical professor of speech, language, and hearing sciences.

ARC typically sees about 80 to 90 people per week. On the research end, “we have, at this point, over 500 patients in our database,” says ARC research director and CBR founding director Swathi Kiran, the James and Cecilia Tse Ying Professor in Neurorehabilitation at Sargent. “They enroll in randomized control trials or treatment studies. At least 200-plus of them are people who are bilingual—we are focused on understanding how the bilingual brain recovers from a stroke.”

In one recent study, BU researchers, led by Kiran and PhD student Manuel Jose Marte (Sargent’25), analyzed whether machine learning models could predict language recovery in 48 English-and-Spanish speakers who had aphasia from strokes. Accounting for varying aphasia severity and education levels, the researchers not only wanted to predict who would benefit from language therapy, but also whether the patients would improve in both languages.

The study showed that machine learning models could predict treatment outcomes relatively successfully—potentially helping clinicians better tailor therapies for bilingual patients—and that factors such as the severity of language impairment mattered for predicting improvement.

“With the rise in the Hispanic population in the US, the higher risk of stroke in this community, and the fact that the aging population is also increasing in this country, finding effective and efficient therapies for these adults is even more important,” says Kiran, who receives funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and last year won the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association’s (ASHA) highest award, the Honors of the Association. She’s also the cofounder of and scientific advisor to Constant Therapy Health, which offers digital therapeutic programs and apps for at-home speech, language, and cognitive rehabilitation practice.

Research also informs ARC’s community programs, like its book club. Working with collaborator Gayle DeDe (Sargent’07), a research associate professor at Temple University, Hoover has an NIH-funded grant for a clinical trial looking at the efficacy of conversation group treatment. (Hoover and DeDe first worked together when the latter was a BU student, and they founded Sargent’s Toastmasters program.) Hoover says it’s the first study of a “group, participation-based treatment that’s been funded by the NIH to date.” With 200-plus participants, it’s also the largest study of its kind, she adds. While data is still being analyzed, initial results suggest that people can benefit from conversation treatments; a deeper data dive, the researchers hope, will allow them to target the best candidates for such therapy.

People need to connect with a community. They do better when they have a sense of this community, that they’re not alone, that they haven’t lost their intelligence, and that there is hope for change.

“People need to connect with a community,” says Hoover, an ASHA lifetime fellow and Tavistock Trust for Aphasia Distinguished Scholar Award winner. “They do better when they have a sense of this community, that they’re not alone, that they haven’t lost their intelligence, and that there is hope for change. You can continue to make changes in your language and your functional communication for decades after your stroke, as long as the intervention and the type of treatment you’re engaged in is appropriate.” (One problem, Kiran says: health insurance covers the emergency treatment that stabilizes stroke patients to send them home, but then often gives only limited coverage for the therapy to recover language and speech skills.)

By treating patients while conducting research, BU is “not just saying we’re trying to understand what aphasia is, we’re also actually helping you on a daily basis,” says Hoover. “I think our clients feel honored when they participate in research.”

A History of Aphasia Research at BU

The University’s interest in aphasia treatment dates back to the 1960s, but it was at the beginning of this century that it began to become a national hub for research and practice. For Kaplan, the decision to join BU owes in part to the University’s simple courtesy of answering a question.

In the 1990s, Kaplan, then at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital (Boston), launched monthly meetups for patients with aphasia, but eventually realized he had to expand services, given the varying needs of attendees. He broached collaborations with multiple universities and hospitals. “The only one to even respond was Gloria Waters and Sargent College,” he says.

Waters—now University provost and chief academic officer, and previously a Sargent professor, then dean—is a leading scholar of language and memory who codeveloped an assessment battery for aphasia. Kaplan decamped for BU in 2006, where he joined another recent recruit—Hoover, who’d already started running some treatment groups with Waters. Together, they founded the Aphasia Resource Center with funding from the Boston Foundation and BU alums Mynde S. Rozbruch Siperstein (Sargent’78) and Gary S. Siperstein (Questrom’80).

The Center for Brain Recovery launched in 2022 with the goal, Kiran said then, “to become a national, international, premier center to understand, diagnose, and treat individuals with brain disorders,” including aphasia. The center grew out of Sargent’s long-running Aphasia Research Laboratory. Among its current projects are a collaboration with the BU Neurophotonics Center to track post-stroke recovery via a wearable system that uses infrared light to measure brain function and a partnership with BU computer scientists to develop AI algorithms to better predict patient rehabilitation.

Kiran echoes Kaplan in saying one size does not fit all for people with the disorder, with this caveat: some kind of interactive therapy, along the lines of ARC’s offerings, remains essential. There are medicines that studies suggest might help, she says, “but the scientific evidence has not found that to be more effective than rehabilitation. There are some very compelling studies that you can stimulate the brain by providing electrical current. But even those are effective only when you give it with therapy.”

In addition, Kaplan says, “it matters to the patients that we are contributing to these young healers”—the supervised BU students that support research studies, help with programs like Toastmasters, and facilitate many of ARC’s meeting groups, getting real-world experiences of working with patients. “It’s different from going through a hospital where you’re being ‘fixed.’”

That matters to the young healers, too. Finnegan says that working with patients, particularly through Sargent’s Toastmasters program, “has already made an impact on me—seeing the community that Toastmasters has created.” Initially inclined toward pediatrics, she adds, “after learning more about aphasia and experiencing Toastmasters, I do think I would be interested in broadening my experiences and working within a medical setting for both children and adults. I am particularly interested in stroke recovery and the VA hospital programs for retired veterans.”

“It goes back to something a client said to me decades ago,” Kaplan says. “‘It’s not that I’m recovering from aphasia, but that I’m recovering with aphasia,’ and it means it’s like diabetes or any chronic condition—I can not only live, but I can also thrive with my community and my supports.”

Supports like the encouragement doled out at Sargent. The last speaker at that Toastmasters session, Ken Behar, details the improvement in his walking since his stroke, such as the surprised faces of fellow pedestrians in his hometown who see him without his rollator. Afterwards, one of the interns, Lindenberg, compliments him on his detailed description: “I felt like I was walking with you.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.