BU’s Initiative on Cities Builds a Tool for Fighting Displacement

Keeping people in their neighborhoods in Louisville, Ky., means assessing proposed developments

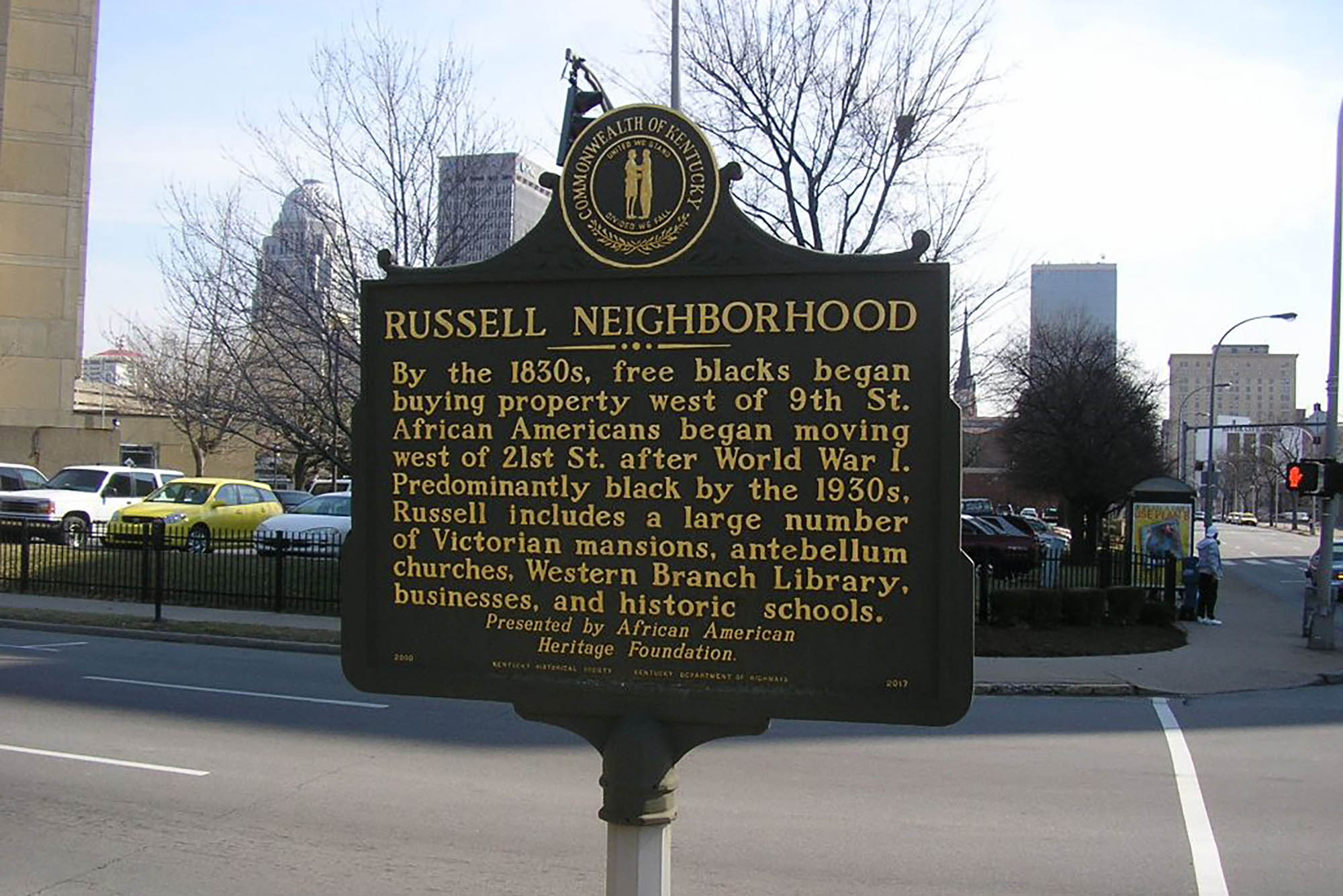

Campaigners in Louisville, Ky., successfully pushed for an ordinance to deny city support for construction projects that would displace existing residents, particularly in historically Black neighborhoods like Russell. Photo courtesy of Wiki Commons

BU’s Initiative on Cities Builds a Tool for Fighting Displacement

Keeping people in their neighborhoods in Louisville, Ky., by assessing proposed developments

Activist Jessica Bellamy owns the house where she grew up, in the historically Black neighborhood of Smoketown near downtown Louisville, Ky. Around 2020, she says, she began planning a modest renovation, but none of the local contractors wanted the job because they were all booking more profitable projects in the neighborhood. Smoketown was under strong gentrification pressure that would soon spread to other historically Black neighborhoods nearby.

Families with deep roots were being pushed or bought out, says Bellamy, houses and apartments renovated and flipped for big profits. A home that would have sold for $30,000 a decade ago, for instance, could be flipped for as much as 10 times that; a housing project was made over as a mixed-use development unaffordable to many residents. One aspect that especially rankled: some projects involved government grants, tax breaks, and other assistance for developers. Public investment became private profit.

It was happening in other cities, as well. “The main difference between us and other cities, especially in the South, is that we organized,” says Bellamy, cofounder of the Louisville Tenants Union.

She led a campaign that culminated in the late 2023 passage of an anti-displacement ordinance to deny city support to projects that would push neighborhood residents out of their homes. To help implement the new law, the city turned to Boston University’s Initiative on Cities (IOC) to build a tool to assess whether proposed residential developments would be likely to do so.

“It’s not about stopping development, it’s about making sure that government doesn’t subsidize the displacement of the existing residents,” says urban planner Kenton Card, who worked on the project as the IOC’s inaugural postdoctoral research fellow.

It’s not about stopping development, it’s about making sure that government doesn’t subsidize the displacement of the existing residents.

The open-source tool includes a web form where users input information about a proposed project; the tool crunches the data and reaches a conclusion about its likely impact on current residents.

“What it does that’s different to other models is, we situate the project in the context of what’s going on around it,” says Loretta Lees, faculty director of the IOC. The tool “takes the number of bedrooms, the number of units, what the rents are going to be, what rents that they’re asking, and then it puts that in the context of the wider area,” beyond simply the footprint of the project or even the immediate neighborhood.

The tool first calculates a specific location’s displacement risk level, which is determined by a simple algorithm using data from the Census Bureau, the Louisville Metro Government, and private data providers. Each risk level—low, medium, or high—is associated with a set of requirements, such as the share of affordable units each project must contain. The higher the risk, the more stringent the requirements. In the second step, a user provides data about a development project to determine if it satisfies the requirements associated with the neighborhood’s risk level and is eligible to receive city support. In theory, the community can use the process to leverage changes from developers to make projects more affordable.

The ultimate goal is to keep gentrification from pushing people out of the neighborhoods they’ve long called home—but to do so without preventing development. “Gentrification is bad, and it’s bad because it displaces low-income, marginalized, often racialized groups,” says Lees, a BU College of Arts & Sciences professor of sociology.

Passing the Nation’s First Anti-Displacement Ordinance

Residents of historically Black neighborhoods on the west side of Louisville, including Smoketown, have long been disadvantaged by racist practices, such as redlining. Public housing has been demolished and replaced with less affordable mixed-use developments. As the real estate market in the city began to heat up in recent years, the tenants union fought back.

“They got the first anti-displacement ordinance in the country passed through lots of groundwork with Councilman Jecorey Arthur,” says Lees. “They had to do so much to get this passed, it was unbelievable. And as part of the ordinance, the city had to get academics to develop an anti-displacement assessment tool.”

The ordinance also created a commission to review city anti-displacement policy, work on restitution for people who were victims of housing discrimination, and participate in regular updates to the city’s housing needs assessment.

“We wanted to work on policy to address the housing crisis, and we thought that gentrification was something that we could do something about,” says Arthur, who left the council at the end of 2024 and teaches music, sociology, and community organizing at Simmons College of Kentucky.

Arthur says a surge of activism followed the Louisville police killing of Breonna Taylor in 2020. Taylor lived in a historically Black area targeted for development, and activists wanted to address a set of interconnected social ills, from police violence to lost housing. An anti-displacement ordinance was near the top of their list.

“We had people showing up to meetings, knocking on doors, helping us share on social media. About a thousand people were organized across all 26 of our metro council districts to work on this anti-displacement law,” Arthur says. “And we did it because people weren’t able to afford housing. We were being priced out of our neighborhoods, communities that we lived in and called home for so long.

“There was a vested interest from the organizers who have struggled with housing stability,” he says. “And it was an example of government officials and policymakers working with organizers to get something accomplished.”

The IOC won the tool development contract and started work last summer.

“These places do desperately need investment, but it has to be the right kind of investment,” says Andre Comandon, another member of the team behind the tool and a research scientist at the University of Southern California’s METRANS Transportation Consortium. An expert in quantitative analysis, he has a background in studying segregation and urban inequality.

“Housing is one of the big political fault lines of our time,” says Card, who’s now a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Minnesota. “It is connected to racial exclusion. It is connected to the stagnation of wages. It is connected to middle-class wealth, and how that’s being racialized, and urban centers becoming gentrified and folks being pushed [out]. We need to open up our eyes. The role of the government is going to continue to change, and I think this is a great tool.”

Not everyone supported the 2023 ordinance, including Louisville’s Democratic mayor, a developer himself. But a late-2024 city council resolution to put the tool to work was more widely backed, in part because the expertise and credibility of the IOC team made it clear the effort was more data-based and less political. “When they were able to help us apply pressure from a place of objectivity, it really helped us solidify this as a solution,” says Arthur.

That’s where Lees’ experience—including as chair of the London Housing Panel in the United Kingdom before moving to Boston in 2022—came in handy. She says language is important in building consensus, especially on a politically fraught topic like this.

This is anti-displacement, not anti-development … We focus on displacement, because that is the bad thing. They still want development and they want development downtown.

“This is anti-displacement, not anti-development, because it’s a small city like Louisville, where gentrification is emerging, but it’s not like New York or Boston,” Lees says. “We focus on displacement, because that is the bad thing. They still want development and they want development downtown.”

Once the tool produces some results, Lees says, “it will really get developers thinking about the impact of their project in a neighborhood, not just their own bottom line. So it becomes a very ethical process in many ways. Developers are not trained in general to think that way, but this model kind of pushes them into that direction.”

Lees says the team will write an academic paper about the project. “We don’t really know yet what the end result is, how it really works, practically,” she says. “What we might do is apply for money now to do some analysis, and once the tool’s operative, come back four years later and evaluate what the tool has done.”

In the meantime, the tool was designed to be easily replicable in other places, Lees says. Housing activists in several other cities, including Greenville, S.C., have reached out to express interest.

“We’ve had some southern cities and towns call us interested in having some sort of training to pass their own policy,” says Arthur. “There’s an urgency because people are becoming unhoused at extreme rates. We wanted to do something to prevent that. And stopping government action from displacing people was one of the easiest ways to do it, because government can control what government does.”

Having the IOC come on board “was so important because we needed them to put the tool together,” says Bellamy. “But they definitely needed our guidance, influence, and experience to know really what the problem looks like. There’s a saying that ‘Only the person wearing the shoe knows where it pinches.’”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.