“I Felt Very Alone”: Living with an Eating Disorder at BU

A Sargent student shares her journey, her struggles, and how she helped create a support group on campus. Plus, more eating-disorder resources available to students

Celine Uhrich (Sargent’27) was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa as a teenager. The peak of her eating disorder came as she was beginning her BU freshman year.

“I Felt Very Alone”: Living with an Eating Disorder at BU

A Sargent student shares her journey, her struggles, and how she helped create a support group on campus. Plus, more eating-disorder resources available to students

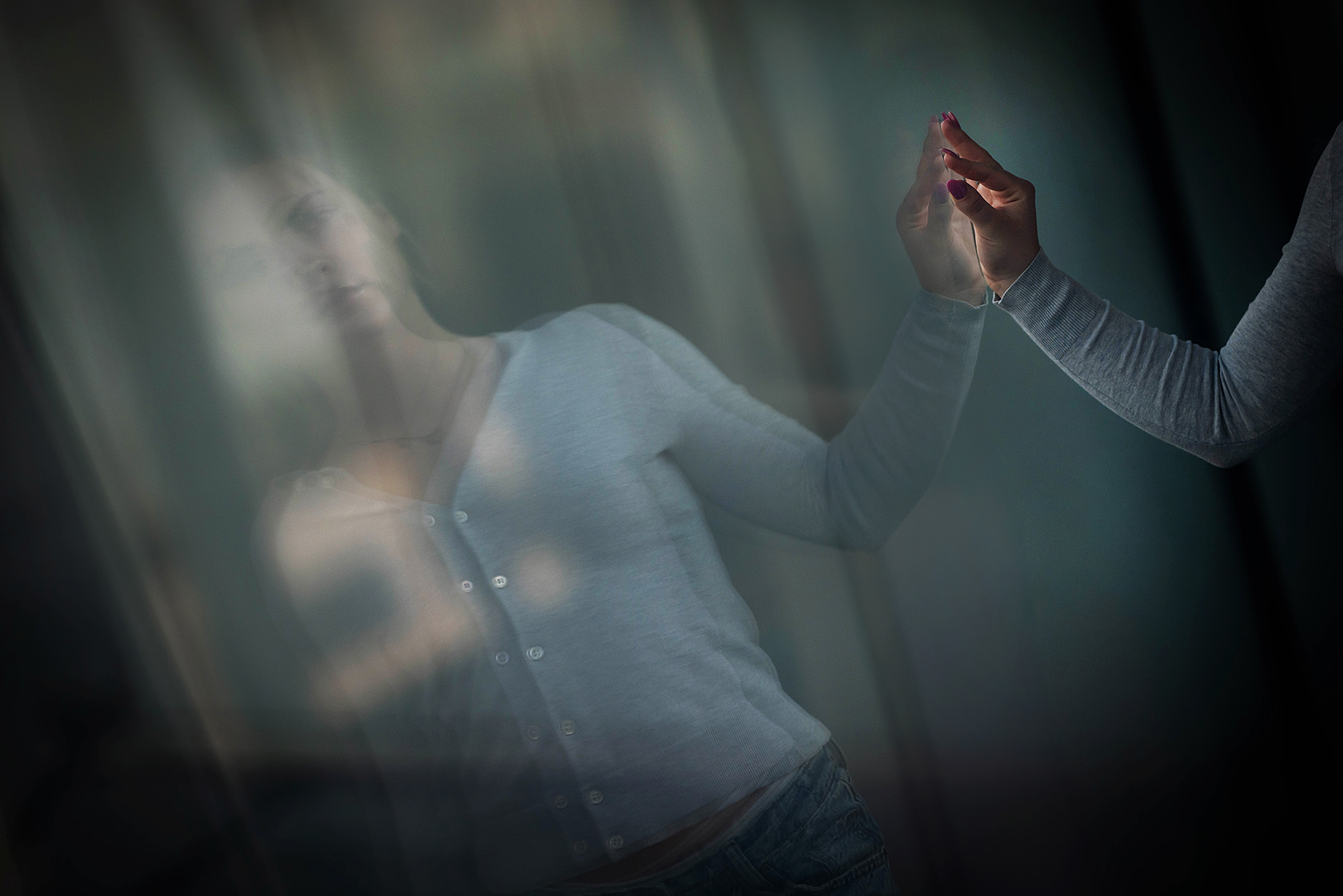

How much lower can I go before I get sent to the hospital?

At the peak of her eating disorder, that was the question Celine Uhrich asked herself every time she stepped on the scale.

Uhrich (Sargent’27), a sophomore in Boston University’s Sargent College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences and an architect of an eating disorder support group on campus, has struggled with disordered eating almost her entire life. Chronic gastrointestinal issues in her childhood led her to implement strict food restrictions that developed into anorexia nervosa as she got older.

Her rock bottom came in 2023, she says, just as she was set to start her freshman year at BU. By that point, she was severely restricting food and exercising to the point of exhaustion. She knew she was on a dangerous path—anorexia has the highest fatality rate of any psychiatric disorder—but she didn’t care.

When you have an eating disorder, Uhrich stresses, so much of your behavior is beyond your control.

At her worst, she says, “I only knew that I wanted to be the smallest version of myself. My mind would just constantly be on food, be on exercise, and there was no time to think about anything else. No one in my life mattered at that time—I didn’t matter. I was just a ghost, floating around my life.” She could see that she was scaring her family, but she couldn’t stop.

Uhrich started a virtual hospitalization program in fall 2023, the day her classes at BU began. The program required her to be on Zoom for six hours a day, mimicking the time she would spend in a medical facility in a partial inpatient program. It quickly proved difficult to juggle classes and the program. Her dorm accommodations were also a challenge. She couldn’t get a single room to do the program in private, nor did she have access to a kitchen to cook her own meals. (Looking back, Uhrich says, she should have taken a gap semester to enter treatment, but she was excited about starting at her “dream school” and didn’t want to put it off.)

“The whole experience was very isolating,” she recalls. “I felt very alone—I felt like nobody outside of my family cared that I was going through this or felt like it was a real issue.”

The pressures mounted. She was hospitalized around three weeks into the semester. She spent four days at Mass General Hospital being treated for malnourishment. In the hospital, she finally had an answer to her recurring question. But it only opened the door to a new, more pressing one.

“The goal was to push myself [to lose weight] until I ended up in a hospital,” Uhrich says, “and I reached that point.” All that was left for her to think was: now what?

“Anyone can have an eating disorder”

Approximately one in every five BU students likely struggles with some form of disordered eating.

According to BU Behavioral Medicine, Student Health Services (SHS) mental health arm, 17.6 percent of students who came into SHS from January 2024 through January 2025 screened positive for eating and body image concerns during their initial appointment. The BU Healthy Minds Study, an annual survey of mental health trends in college students, identified that 15 percent of BU students in 2022 had a probable eating disorder. (Another 35 percent of students indicated in the survey that they need to be very thin to feel good about themselves.)

Statistics from the Academy for Eating Disorders and a Harvard University public health incubator show that 9 percent of Americans will struggle with some form of eating disorder in their lifetime.

Eating disorders are a broad category that cover more well-known diagnoses like anorexia or bulimia, but can also include behaviors and conditions such as food avoidance or restriction, bingeing or purging, orthorexia, a fixation on “clean eating,” abusing diet pills or laxatives, unnecessary fasting, limiting and counting calories, and overexercising. (Note: “eating disorder” and “disordered eating” are almost-but-not-quite interchangeable terms—disordered eating usually implies some of the same behaviors as an eating disorder, but with less frequency or severity.)

The dangers of eating disorders are well documented. They can be fatal, even with intervention. People with eating disorders can also develop significant health issues: irregular heart rate or heart failure, anemia, loss of tooth enamel and bone density, electrolyte imbalances, decreased thyroid functionality, weakened immune response and wound-healing ability, neurological disorders, and seizures are all possible complications. Some complications can be permanent.

Women are two times as likely to be diagnosed with eating disorders as men, but they impact all races and genders and can come into play at any age.

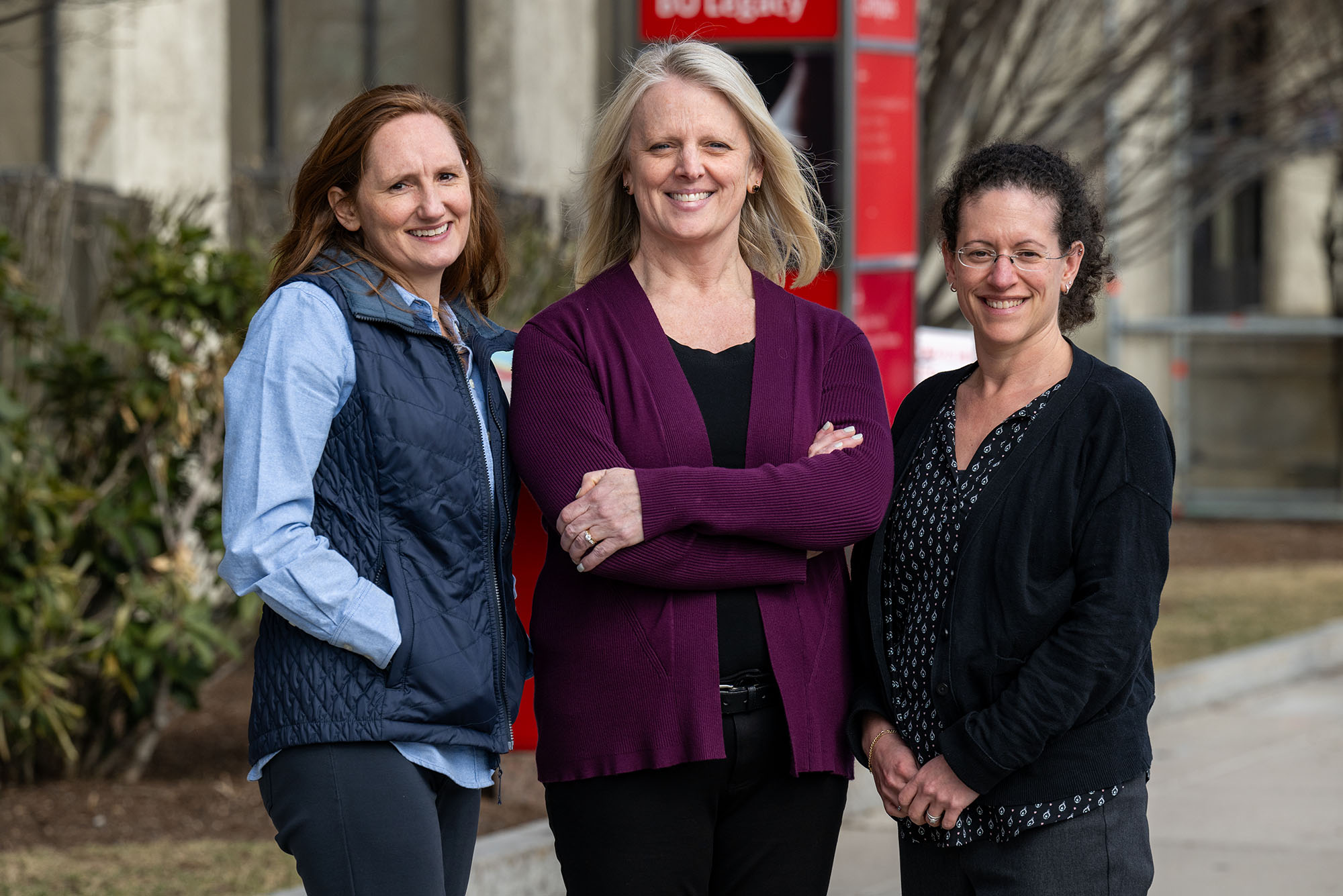

“People often have this idea that someone with an eating disorder needs to look a certain way, but anyone can have or develop an eating disorder,” says Ilana Licht, a Behavioral Medicine psychologist who specializes in eating disorders and is the facilitator for Nourish & Flourish, the University’s eating disorder support group. “It doesn’t matter your gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, or body shape or size. Most of the time, you can’t tell who has an eating disorder based on what someone looks like.”

Another misconception: that it’s someone’s fault if they develop an eating disorder or if they struggle to recover.

An increasing amount of research points to there being a genetic component to some eating disorders. Other research suggests that some people’s brains simply respond to food differently. So if someone is predisposed to an eating disorder, triggering circumstances—like starting college alone in a new city—can contribute to a pattern of behaviors that once started, are difficult to stop. For many, disordered-eating behaviors can also serve a larger purpose: stress relief, fitting in, gaining a sense of control, or myriad other purposes. Letting that go can be challenging, especially without support.

People often have this idea that someone with an eating disorder needs to look a certain way, but anyone can have or develop an eating disorder.

“Eating disorders are a very serious illness,” Licht says, and they’re sometimes downplayed by people who don’t understand them. “They’re not just a mental health issue; they’re a biological illness. So the idea that, ‘well, this person could just get better if they wanted to’—well, no, not without a lot of treatment and support.”

“A space to rant”

Nourish & Flourish meets on Zoom on Tuesdays from 5 to 6 pm. Every session starts with a five-minute meditation to help participants center themselves and identify what it is they’re feeling that day. After that, Licht guides the group through conversations.

Uhrich completed the virtual hospitalization program after being released from Mass General. The program changed her life at a time she needed it most, she says. It also allowed her to think about: now what?

Her answer: helping others like her access support and community on campus.

At the start of her sophomore year, she reached out to Behavioral Medicine about offering a support group for students dealing with, and in recovery from, eating disorders. Behavioral Medicine, which has offered a support group on and off over the years, was happy to oblige. Nourish & Flourish—formerly known as Body & Self—officially began with the start of the spring 2025 semester.

The group is small so far, but Uhrich has hopes that it will expand as more people become aware of it.

More than anything, the group is “a space to rant with a licensed therapist,” she says. No one’s going to preach at you or judge you for your experiences. The purpose is to simply connect you with people who understand what you’re going through.

“It’s not about providing solutions,” she says, “but about getting that therapeutic support that I believe everyone who’s struggling with [eating disorders] needs.”

Support on campus

Nourish & Flourish is only one of the resources available to BU students. BU has its own long-standing multidisciplinary eating disorder response team.

“There are really so many things in the college setting that can create the perfect storm for eating disorders and disordered eating,” says Elizabeth Matteo (Sargent’16), a nutritionist at BU’s Sargent Choice Nutrition Center. “Stress, changing social dynamics, losing your [at-home] support system, navigating the dining hall, the challenge of trying to schedule meals around classes—all of these can be contributing factors.”

Twice a month, staffers from Behavioral Medicine, SHS Primary Care, Athletic Training, and Sargent Choice meet to talk about, and coordinate, care for BU students experiencing eating disorders and disordered eating. While BU can support students experiencing a variety of issues, the departments will refer students who need more intensive care—such as inpatient treatment—to local organizations that the University has relationships with.

So what does support at BU look like?

When a student first accesses support, SHS will conduct a medical evaluation to help determine if the student is stable enough to be treated at the outpatient level. From there, Primary Care will monitor them—running blood tests, taking vitals, watching for complications—throughout their treatment journey. Beyond Nourish & Flourish, Behavioral Medicine offers individual therapy and community provider referrals. Both departments can also connect students with additional resources at BU and beyond.

At Sargent Choice, Matteo and her colleagues work with clients to develop specialized nutrition plans. (BU students are eligible for up to three nutrition-counseling visits free of charge. Learn more about the policies here.)

Nutrition planning for someone with an eating disorder can require great care, Matteo says. Her number-one goal for her clients: meeting nutritional adequacy. The secondary goal: balance.

For example, if a student has only a handful of “safe” foods that they’ll eat, she says, she’ll first work with them to make sure they’re eating enough of those foods to meet their daily energy needs. Then they’ll slowly incorporate more foods, including varieties within a food group and items from different food groups. Other things they might work on could be flexibility, such as identifying strategies for deciding what to eat if a dining hall menu changes or if a friend extends a last-minute invite to grab dinner. For students experiencing disordered eating, Matteo will often work on promoting a balanced relationship with food and establishing a consistent eating pattern.

“These things can be really challenging for people,” Matteo says. “Whenever we’re creating a plan for nutrition, we’re always meeting the person where they are.”

Athletes are an overlooked group

Athletic Training has its own behavioral health team that oversees any mental health issues BU athletes may be experiencing.

Athletes are a high-risk, yet often overlooked, population when it comes to eating disorders. Combine intense training schedules with diet restrictions, pressure to perform, often in front of crowds, and a perfectionist streak inherent in many athletes—to say nothing of the revealing uniforms of some sports or the need to maintain certain weights in other sports—and you have a highly effective recipe for food and body-image issues, says athletic trainer Bridget Salvador.

There are really so many things in the college setting that can create the perfect storm for eating disorders and disordered eating.

The behavioral health team’s job is to recognize mental health issues and connect athletes with the proper resources. They also help make sure athletes get to appointments and receive accommodations they need. Salvador and her fellow athletic trainers are constantly on the lookout for signs of disordered eating in the athletes they work with. There are physical symptoms to watch for, like weight loss or weight gain, chronic exhaustion, and stress fractures, which athletes with eating disorders can be especially prone to. But eating disorders are often invisible. Behavioral assessments and close monitoring are critical for timely interventions.

“The nice thing about us as athletic trainers is that we travel with a lot of our teams, so we’re with them all the time,” Salvador says. “We can watch for things like, are they skipping team meals or not eating during meals? Are they self-conscious when they’re getting into their gear? Is their personality changing? Are they not hanging out with their teammates anymore? Those are all things that we’re able to observe firsthand.”

For athletes particularly susceptible to eating disorders and stress fractures, like long-distance runners, Athletic Training recently started using an assessment tool that separates athletes into different risk categories, so athletic trainers and coaches know who to keep a closer eye on.

There’s a fine line between taking good care of yourself and obsessive, harmful behavior, Salvador says, and it can be tricky to get someone to realize that they’re engaging in destructive behaviors.

But it’s not impossible. “We’ve had some really big success stories” over the years, she says. “Finding confidence and contentment within yourself is such a huge piece of becoming an adult. If you can help someone do that, it’s just really amazing.”

All of these departments stress how much of their work involves education. In today’s image-focused culture, fad diets and exercises and general health misinformation are rife online. It can be difficult to parse what’s real and what’s harmful—or what’s just trying to sell you something. Helping students cut through the noise, especially when it comes to wellness, is crucial.

“I think of wellness like I think of toxic positivity—taglines like ‘it’s okay not to be okay’ can be overused and lose meaning,” says Erika Thomson, assistant director of outreach and prevention in Behavioral Medicine and an evaluating clinician for students first entering the Behavioral Medicine system.

Part of Thomson’s job involves educating students on mental health topics one-on-one and at outreach events. She and her staffers always try to “pull back the curtain,” she says, on what students might encounter online, and provide them with accurate information.

“I always like to explain that what works for you may not work for someone else,” Thomson says. “A lot of what we do [involves] normalizing what it actually looks like to get into a wellness routine and helping someone define that for themself.”

“Recovery is possible”

Now in her sophomore year, Uhrich is in a far better place than she was last year.

Her hospitalization was a wake-up call. She learned she could have died from refeeding syndrome, a series of complications that can occur after reintroducing food to a malnourished body. She also realized just how much anorexia was controlling her life and alienating her from the people who love her.

She recently participated in a treatment program at the Renfrew Center for Eating Disorders. It’s one of the organizations that BU has a relationship with, and it’s conveniently located on the Charles River Campus. The program helped reframe Uhrich’s thinking about her body and her urges. It also reminded her that progress isn’t linear. Recovery is hard—sometimes really hard—but fighting to live her life for herself, not her “eating disorder brain,” is worth the uncomfortable moments, she says.

Uhrich reflects on her recovery journey in a post for National Eating Disorder Awareness Week in early March. Courtesy of Celine Uhrich/Instagram

A big part of her recovery has involved reconnecting with her body. She’s learning to move for enjoyment, not out of obligation. She’s now a certified yoga instructor and runs an Instagram account, where she documents her recovery journey and shares tips for mindful workouts. She hopes talking about her experience destigmatizes eating disorders and disordered eating. She also hopes it highlights the importance of supporting individuals who are struggling.

“I think a lot of people believe that eating disorders are a decision [someone makes], but that is just so not true,” Uhrich says. “As a human, why would you want to be in pain?” Recovery also isn’t a one-and-done deal, but a continual effort, she stresses. “One second you think you’re okay, and then the next second you’re not. It’s a constant cycle.”

On her hardest days, Uhrich tries to remember why she wants to get better in the first place. Besides being there for her loved ones, “one of my biggest motivations is to help other people, and I can’t help other people if I’m not helping myself,” she says.

“That’s my motivation: to not be in pain,” she continues. “I know that [outcome is] out there—it’s the light at the end of the tunnel, it can just be hard to see. Recovery is possible.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.