BU Sargent College Team Helps Design New Middlesex Jail Unit for Incarcerated Older Adults

Roger Richardson, 59, describes the Older Adult Re-Entry Unit as “quieter, calmer, and more comfortable” compared to being housed with the general population.

BU Sargent College Team Helps Design New Middlesex Jail Unit for Incarcerated Older Adults

Faculty advise on a wide range of issues, from accessible furniture to treatment, education, and training

Roger Richardson has been in and out of jail for nearly 40 years for various offenses, including drug possession, and most recently, probation violation. In October, while incarcerated at the medium-security Middlesex Jail & House of Correction in Billerica, he was invited to apply to the jail’s new Older Adult Re-Entry Unit (OAR).

The unit, created in collaboration with a team from Boston University’s Sargent College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences, provides age-appropriate care for incarcerated adults aged 55 and older. It aims to prepare residents for life after incarceration by teaching skills for independent living—all residents are required to participate in occupational therapy and rehabilitation programming designed by the Sargent team—with the ultimate goal of reducing recidivism.

“It’s been pretty good, you know?” says Richardson, speaking candidly about his experiences inside the unit. With graying cropped hair and dressed in a prison-issued hunter green uniform, the 59-year-old describes the unit as “quieter, calmer, and more comfortable” compared to being housed with the general population. He has enjoyed the unit’s programming, which includes language classes, Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, and occupational therapy, all aimed at stimulating the mind and preparing the men for life outside prison walls.

“It’s helped me a lot,” Richardson says. “I’d definitely do it again if I had to—but hopefully, I never have to come back.”

About 20 men, both already incarcerated and those awaiting trial, live in the voluntary unit, which doesn’t look like the rest of the jail, except for the grates on the windows and the fact that the door still locks from the outside. It has been specially designed to meet the needs of older adults. There are no upper bunks, which can be difficult for older adults to climb into. OAR’s beds, arranged in neat rows instead of individual cells, are raised to make it easier for residents to get in and out. The unit also has padded rocking chairs to stimulate the brain’s balance systems, low-threshold shower stalls to prevent tripping, and directional signage on the floors to reduce the risk of falling.

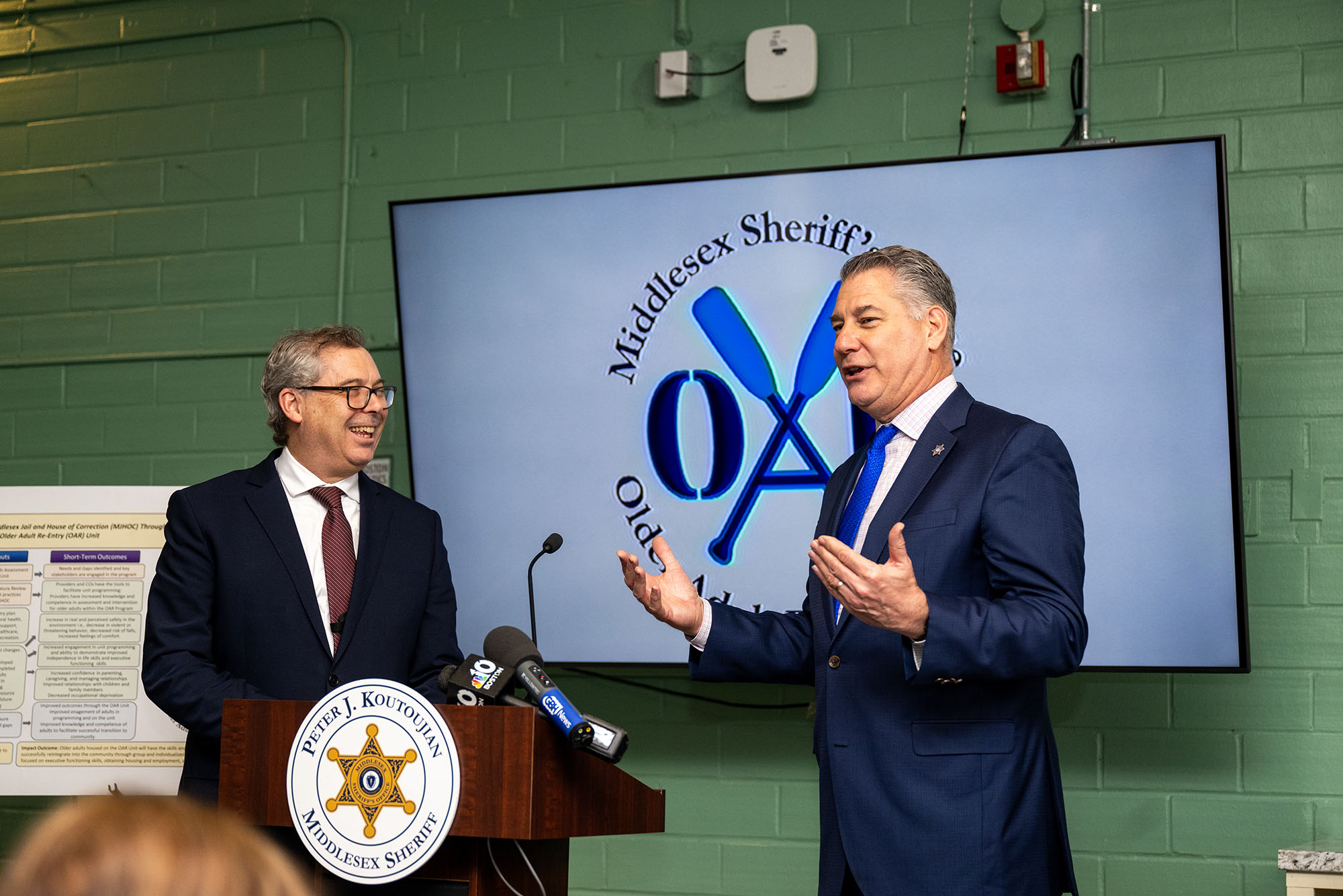

At the March 21 opening ceremony and tour of the facility for government officials and the press, Middlesex County Sheriff Peter Koutoujian said that while specialized jail units that house older populations exist, Middlesex officials believe OAR is the only unit in the country that combines specialized accommodations for older adults with rehabilitation programming.

We are truly thrilled to be part of this innovative and groundbreaking project that is first of its kind in the United States.

“We are truly thrilled to be part of this innovative and groundbreaking project that is first of its kind in the United States,” Sargent Dean Jack Dennerlein said at the event. He believes that OAR will make a meaningful impact on the lives of those in the unit and the communities they return to after incarceration, as well as on Sargent’s students and faculty. Dennerlein says his hope is that the unit can “pave the way for a more equitable and rehabilitative approach to corrections.”

A growing need for specialized care

Older adults are the fastest-growing demographic in the United States and also the most rapidly growing population of incarcerated adults. The proportion of state and federal prisoners who are 55 or older is about five times what it was three decades ago. This trend is driven, in part, by longer life expectancy, harsher sentencing (in some cases), and the rising criminalization of poverty.

Older incarcerated adults also face higher rates of chronic diseases and victimization compared to the general population, making them the most costly population to house. Research also shows that incarceration accelerates the aging process.

In 2019, Koutoujian had the idea of creating an older adult reentry preparation unit similar to other targeted units inside the Middlesex facility, like ones for young offenders ages 18-24 and for military veterans. He searched for an older adult reentry unit somewhere in the country, with the idea that the Middlesex facility could replicate and modify it to fit their needs. After a nationwide search, he found many geriatric and elder healthcare units, but no units created with therapeutic and programming aspects in mind, he says. So, he and his team set out to create one.

They first consulted with UMass Boston’s Gerontology Institute and the UMass Boston sociology department to conduct a needs assessment of the older population at the Middlesex facility. Older adults face specific challenges in jail, says the UMass assessment’s coauthor Laura Driscoll (Sargent’99,’01), a UMass alum and a Sargent clinical assistant professor of physical therapy. Her recently published dissertation focuses on her work on the project over the last few years.

“Older adults tend to have worse hearing and vision issues, and they can’t always hear the instructions they are supposed to follow, or even be able to visually identify where they are supposed to go,” says Driscoll, a board-certified geriatric physical therapist. “And they may not have access to the typical things that older people have, such as specialized meals, even a walker or a cane.”

[Older adults in jail] may not have access to the typical things that older people have, such as specialized meals, even a walker or a cane.

The research shows that they are at a disadvantage socially, too. “If they’re snoring in a dormitory-like setting, other people can get really aggravated because they’re causing a disruption,” Driscoll says. “That makes them fear even sleeping. In carceral settings there are lots of relationships that form, and sometimes they want to not be involved in the drama, but they have a fear of not participating.” In their final assessment, the UMass team stated that the Middlesex Jail’s aging population would greatly benefit from a specialized housing unit and accommodations.

Fast forward to 2023, when Shawn MacMaster, Middlesex assistant superintendent of program services, emailed Emily Rothman, a Sargent professor and chair of occupational therapy. A simple Google search had told him that BU has the best occupational therapy program, so he thought a partnership might work. Her staff was thrilled by the invitation.

“We got a tour and drew up recommendations,” says Anne Escher (Sargent’08), a Sargent clinical assistant professor of occupational therapy, who worked alongside Jennifer Kaldenberg (SPH’18), a Sargent clinical associate professor of occupational therapy, and Jennifer Keenan (CAS’07, Wheelock’12,’22), Sargent assistant dean of clinical education administration and community partnerships. “They took every single one.”

The four pillars of OAR

Beyond the physical accessibility enhancements, OAR has four pillars: treatment (including AA meetings and substance use disorder programming), social enrichment (like games and puzzles), education (foreign language, life skills, and book groups), and occupational therapy (goal-setting and achievement, executive functioning skills, self-regulation, and roles, routines, and habits).

Koutoujian says these pillars aim to reduce isolation, foster prosocial behavior, and promote cognitive health. Challenging the mind “is something we focus a little bit more on here than we do in other units since this acts as a protective factor against cognitive decline,” he says.

Sargent’s team, alongside the OAR planning committee (consisting of members of the jail and other academic institutions), created a nine-question screening tool to determine eligibility for potential residents. Most questions have yes or no answers, like “Do you have difficulty bathing or dressing?” “Do you have difficulty walking more than 150 feet, or do you use any device to assist you (like a walker or a cane)?” “Do you have problems with your memory?”

The incarcerated individuals must sign a contract and promise to undergo treatment and programming if selected to live in the unit.

“I assess every individual who is potentially going to be on the unit, and one of the first things I say is that this is a programming-heavy unit,” says Emily Briggs, a Sargent adjunct lecturer in occupational therapy who the school hired to provide services in the OAR unit. “So you can expect, on average, two mandatory programs a day.”

These programs focus on creating healthy routines, managing stress, and using cognitive strategies like visual aids and routines to focus better and finish tasks. There are workshops on digital literacy, financial planning, healthy living, effective communication, self-confidence, teamwork, and family reunification. “We give choices and autonomy where we can,” Briggs says. She notes that the workshops’ goals are to help incarcerated individuals become more independent and to ensure that they are set up for success after leaving jail.

Over the last year, Sargent’s occupational and physical therapy students have also worked in the unit, helping with tasks like needs assessments, an exercise guide, and group therapy.

This month, Driscoll started an exercise program with the men on the unit. They have access to exercise equipment like yoga mats, exercise balls, an elliptical, a rower, and a treadmill, and Driscoll has been interviewing them about their goals. She plans to have Sargent students help lead the training in the fall.

Briggs advises four Sargent doctoral students who currently lead occupational-based groups at the jail. One recent meeting covered how to set realistic goals. An incarcerated individual might say they want to exercise more, but the Sargent team will encourage them to drill down further. “That might mean, ‘I want to use the treadmill three times a week for 15 minutes,’” Briggs says. “Some people have had goals like ‘I want to write a letter to my daughter’ or ‘I want to read more books.’ One guy’s goal is to limit his snack intake because he’s unhappy with the weight he has put on, but we try to write goals in the positive. So it’s framed, ‘I will only have two snacks per day,’ instead of, ‘I will not have any.’”

This fall, Sargent has plans to bring in more graduate and doctoral students from its nutrition and speech, language, and hearing sciences programs.

A national model

Before OAR opened, Sargent’s team trained the corrections officers on age-related changes and how to support these older residents. In the training, they discussed the unit’s background and what happens to the body and the mind as it ages, how to identify common age-related changes and what corrections officers could do to help, the social dynamics geriatric folks face in a correctional setting, and last, how to de-escalate issues.

“If someone seems not to be listening to you when you announce it’s time to hand out medicine, it might just be because they can’t hear you,” says Jennifer Keenan (CAS’07, Wheelock’12,’22), Sargent assistant dean of clinical education administration and community partnerships. “So maybe just go over to them and calmly say, ‘Hey, did you hear that?’ If they start to act differently when the sun starts to go down, it could be a sign of dementia or a sign of general confusion. We took all of these things into account when we were giving suggestions on how to modify the unit, and also in our approach in training the officers.”

Team members say this training has been very well-received by the Middlesex officers, which perhaps isn’t surprising. Existing research on prison officers shows that leading reentry programs and specialized units with a focus on rehabilitation—rather than a punitive approach—has been shown to affect the people working there positively.

Some of this has to do with stress levels. “If everyone is expecting violence [in a prison], then everyone is on edge all of the time,” Keenan says. “It raises people’s stress levels. But there is some evidence to show that having approaches like this, that are targeted toward the actual needs of the people living there, actually reduces the stress on the people who are running the unit, too.” This would be a good area for future Sargent research, she says.

Having approaches like this, that are targeted toward the actual needs of the people living there, actually reduces the stress on the people who are running the unit, too.

Escher says she has noticed a growing enthusiasm amongst the corrections officers assigned to the unit as well. “When the corrections officers see the men putting more into the programming, they want to do more to help them,” she says. “There is this back-and-forth of what rehabilitation is supposed to be like: a collaborative process where the client has autonomy and some choice and some ability to drive some of that. In this environment those opportunities are very limited, but it’s powerful to hear the corrections officers talking about their jobs in a whole other way.”

Koutoujian believes OAR has the power to influence the future of corrections. “This unit is visionary,” he said during the tour. “This can be—and should be—a national model.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.